From Life at Puget Sound, by Caroline Leighton, 1884.

Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

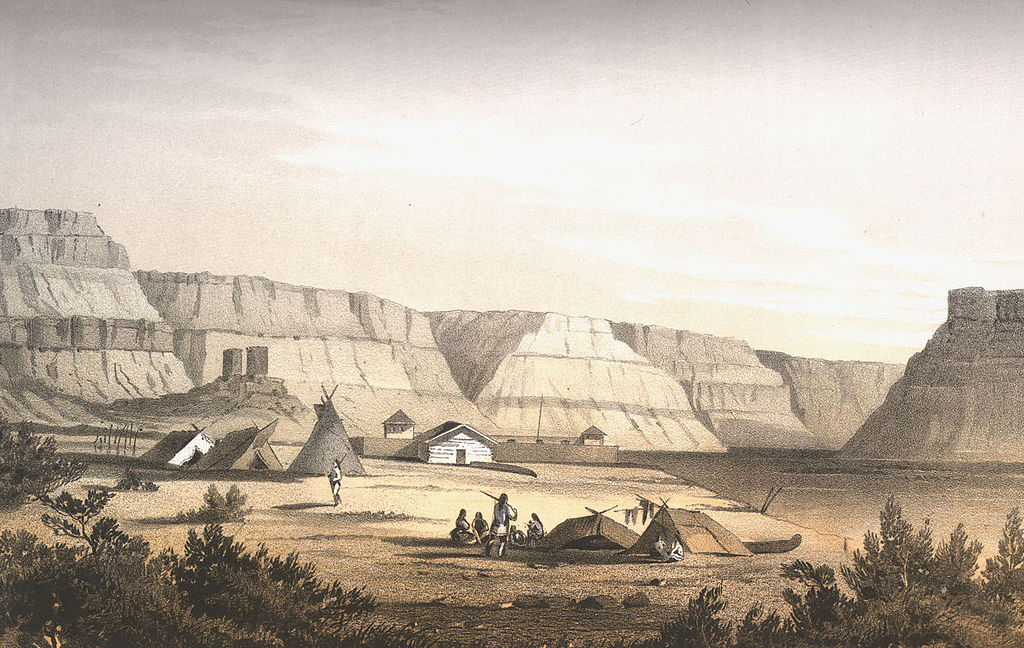

We stopped a day or two at Walla Walla, where one of the early forts was established; the post having been transferred from Wallula, where it was called Fort "Nez Perces," from the Indians in that vicinity, who wore in their noses a small white shell, like the flake of an anchor.

The journey from Walla Walla to Fort Colville occupied eleven days and nights, during which time we did not take a meal in a house, nor sleep in a bed. It was cold, rainy, and windy, a good deal of the time, but we enjoyed it notwithstanding. To wake up in the clear air, with the bright sky above us, when it was pleasant; and to reach at night the little oases of willows and birches and running streams where we camped,—was enough to repay us for a good deal of discomfort. At one of the camping-grounds,—Cow Creek,—a beautiful bird sang all night; it sounded like bubbling water.

For several days we saw only great sleepy-looking hills, stretching in endless succession, as far as the horizon extended, from morning till night, as if a billowy ocean had been suddenly transfixed in the midst of its motion. They have only thin vegetation on them,—not enough to disturb or conceal the beautiful forms, the curves which the waves leave on the hills they deposit. Their colors are very subdued,—pale salmon from the dead grass, or light green like a thin veil, with the red earth showing dimly through. There is no change in looking at them, but from light to shadow, as the clouds move over them.

We travelled, for a long distance, over sagebrush and alkali plains. In this part of the country, sage-brush is a synonym for any thing that is worthless. We found the little woody twigs of it available for our camping-fires; but its amazing toughness reminded me of a story told by Mr. Boiler, in his book "Among the Indians." He was taking a band of mustang half-breeds from California to Montana, when, to his surprise, one of the mares presented him with a foal. Supposing it would be impossible for it to keep up with the party, he took out his revolver to shoot it. Twice he raised it, but the little fellow trotted along so cheerily that his heart failed him, and he returned it to the holster.

The colt swam creeks breast-high for the horses, and travelled on with sublime indifference to every thing but the gratification of its keen little appetite. He resolved to take it through, thinking it would never do to destroy an animal of so much pluck, and named it "Sage-brush." It swam every stream, flinched from nothing, and arrived in good order in Montana, a distance of three hundred miles, having travelled every day from the time it was half an hour old. Its name was most appropriate, as an illustration of the character of the plant.

Intermixed with the wastes of sage-brush were patches of bunch-grass. The horses sniffed it with delight as luxuriant pasturage. It is curious to see how nature here acts in the interest of civilization. The old settlers told us that many acres formerly covered with sagebrush were now all bunch-grass. It is a peculiarity of the sage-brush, that fire will not spread in it. The bush which is fired will burn to the ground, but the next will not catch from it. The grass steals in among the sagebrush; and, when that is burned, it carries the fire from one bush to another. Although the grass itself is consumed, the roots strike deep; and it springs up anew, overrunning the dead sage-brush.

Then we came to the most barren country I ever saw,—nothing but broken, rusty, worm-eaten looking rocks, where the rattlesnakes live. But here grew the most beautiful flower, peach-blossom color. It just thrust its head out of the earth, and the long pink buds stretched themselves out over the dingy bits of rock; and that was all there was of it. We took some of the roots, which are bulbous, and shall try to furnish them with sufficient hardships to make them grow.

One night, while in this region, we camped on a hill where the coyotes came up and cried round us, which made it seem quite wild.

Wherever there was any soil, there was another little plant that was very pretty to notice, both for itself, and because of its adaptation to the climate in the dry season. It was coated with a delicate fur; and long after the hot sun was up, and when every thing else was dry, great diamonds of dew glistened in its soft hair. We saw a great many plants of the lupine family, in every variety of shade, from crimson, blue, and purple, to white.

On the last days we had all the time before us dark mountains, with snow on their summits, and troops of trees on their sides, and ravines with sun-lighted mists travelling through them. It was like getting into an inhabited country, to reach the trees again: they were almost like human beings, after what we had seen. The Spokane River divides the great treeless plain on the south from the timbered mountainous country to the north.

During this journey, we came upon various little bands of Indians, of different tribes. We noticed the superiority of the "stick” Indians (those who live in the woods) over those who live by the sea. The former have herds of horses, and hunt for their living. The Indians who live by fishing are of tamer natures, poor and degraded, compared to those of the interior.

We saw at Walla Walla some of the Klickatats, from the mountains. They were very bright and animated in their appearance, and wore fringed dresses and ornamented leggings, and moccasins of buffalo-skin. They were mounted upon fancy-colored and spotted horses, which they prize above all others. They presented such a striking contrast to the lazy Clalams on the Sound,—who used to say to us in reply to our inquiries as to their occupations and designs, "Cultus nannitsh, cultus mitliglit" (look about and do nothing), as if that were their whole business all day long,—that I was reminded of what some of the early explorers said, that no two nations of Europe differed more widely from each other than the different tribes of Indians.

One day we met an Spokane Indian, of very striking appearance, with a face like Dante's, but with a happier expression. He was most becomingly clothed in white blankets, compactly folded about him, with two or three narrow red stripes across his bonnet of the same material, which had a red peaked border, completely encircling the face, like an Irishwoman's night-cap, or rather day-cap, but much more picturesque. He was scouring the hills and plains between the Snake and Spokane Rivers, mounted on a gay little pony, in search of stolen horses. Upon being questioned as to his abiding-place, he informed us that he did not live anywhere.

We saw some representatives of another tribe of Indians, the Snakes. They call themselves Shoshones, which means only "inland Indians." The white people called them Snakes, probably because of their marvellous power of eluding pursuit, by crawling off in the long grass, or diving in the water. They seemed more wild and agile than any we had seen. The Snakes were a very numerous tribe when the traders first came among them. When questioned as to their number, by the agents of "The Great White Chief," they said, "It is the same as the stars in the sky." They were a proud, independent people, living mostly on the plains, hunting the buffalo. They kept no canoes; depending only on temporary rafts of bulrushes or willows, if not convenient to ford or swim across the streams. They were the only Indians of this part of the country who had any knowledge of working in clay,—their necessities obliging them to make rude jugs in which to carry water across the bare plains.

The mountain Snakes were outlaws, enemies to all other tribes. They lived in bands, in rocky caverns; and were said to have a wonderful power of imitating all sounds of nature, from the singing of birds to the howling of wolves,—by this means diverting attention from themselves, and escaping detection in their roving, predatory expeditions.

When we readied the ferry on the Snake River, we saw some Indians swimming their horses across. They were a hunting-party of Spokanes and Nez Perces. Strapped on to one of the horses, with a roll of blankets, was a Nez Perces baby. This infant, though apparently not over a year and a half old, sat erect, grasping the reins, with as spirited and fearless a look as an old warrior's.

At one of the portages, we saw some graves of chiefs; the bodies carefully laid in east-and-west lines, and the opening of the lodge built over them was toward the sunrise. On a frame near the lodge were stretched the hides of their horses, sacrificed to accompany them to another world.

The missionaries congratulate themselves that these barbarous ceremonies are no longer observed, that the Indian is weaned from his idea of the happy hunting-ground, and the sacrilegious thought of ever meeting his horse again is eradicated from his mind. I thought with satisfaction that the missionary really knows no more about the future than the Indian, who seems ill adapted to the conventional idea of heaven. For my part, I prefer to think of him, in the unknown future, as retaining something of his earthly wildness and freedom, rather than as a white-robed saint, singing psalms, and playing on a harp.

Between the Snake and the Spokane are several beautiful lakes. We met a hunter coming from one of them, who had shot a white swan. He said he found it circling round and round its dead mate, in so much distress that he thought it was a kindness to kill it.

We passed two great smoking mounds, and, on alighting to investigate, found that we were in the midst of a kamas-field, where a great many Indian women and children were busy digging the root, and roasting it in the earth.

Some of the old women wore the fringed skirt, made of cloth spun and woven from the soft inner bark of the young cedar, which they used to wear before blankets were introduced.

The Indians eat other roots beside the kamas, but that is the one on which they chiefly depend. As soon as the snow is off the ground, they begin to search for a little bulbous root they call the pohpoh. It looks like a small onion, and has a dry, spicy taste. In May they get the spatlam, or bitter-root. This is a delicate white root, that dissolves in boiling, and forms a bitter jelly. The Bitter Root River and Mountains get their name from this plant. In June comes the kamas. It looks like a little hyacinth-bulb, and when roasted is as nice as a chestnut. We have seen it in blossom, when its pale-blue flowers covered the fields so closely that, at a little distance, we took it for a lake.

One of the women, seeing our curiosity as we watched them, drew some of the bulbs out of the earth ovens, and handed them to us. As we tasted them, they explained that they were not ready to eat; that it would take two or three days to roast them sufficiently. This they live upon for two or three months; with the salmon, it is their chief article of food. The women stop at the kamas-grounds, while the men go to the fishing-stations.

In August they gather the choke-berry and service-berry, to dry for the winter. When they are reduced to great extremity for food, they sometimes boil and eat the moss and lichens on the trees, which the deer eats. Most of the work of digging the roots, and picking the berries, falls upon the women. On this account, a Spokane man in marrying joins the tribe of his wife, instead of her joining his tribe; thinking, if he takes her away from the places where she has been accustomed to find her roots and berries, she may not succeed, in a new place, in discovering them.

We saw, in the vicinity of the Pelouse River, some remarkable basaltic rocks, that looked like buildings with columns and turrets and bastions. Some of them were like my idea of the great kings' tombs of the Egyptians. The colors on them were often very Egyptian-like,—bright sulphur-yellow, and brown, and sometimes orange and dark red,—incrustations of lichen and weather-staining. We saw, also, walls of pentagonal columns of rock, packed closely together.

Where the Pelouse enters the Snake River, are immense ledges of square blocks. When we camped there, and I lay down beneath them at night, "Swedish trappa, a stair," from the geological text-book, was always running in my mind,—this black traprock made such great steps that led up towards the sky.

We have seen here a splendid specimen of gold, which is to be sent to the Exposition at Paris. It is granulated, and sparkles as I never saw gold before. Some one suggests that a thin film of quartz may be crystallized over it.

Next week we hope to go up within sight of the whirlpools of Death's Rapids, a long distance above here, on the Columbia River. These rapids are so named on account of the number of persons who have been lost in attempting to navigate them. Their names are cut into the rocks at the side of the passage; their bodies have never been found.

Leighton, Caroline C. Life at Puget Sound, with sketches of travel in Washington Territory, British Columbia, Oregon and California, 1865-1881. Boston, Lee & Shepard. 1884.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.