Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“Jamestown, Past and Present” in Round About Jamestown: Historical Sketches of the Lower Virginia Peninsula by J. E. Davis, 1907.

What pictures are conjured up by the name Jamestown, what recollections crowd upon us, what contrasts come unbidden to the mind! Three hundred years ago in this "Cradle of the Republic" lay an infant country, tiny and weak, without money, without food, with nothing, indeed, but an immense though hidden vitality and an unbounded persistence which gave it power to grow in spite of adverse circumstances, in spite of every imaginable drawback, into a mighty nation, a worldpower, stretching out its beneficent hands into the remotest corners of the earth.

In imagination we sail down the Thames in December 1606, with that little handful of English settlers. First southward to the Azores and then westward we travel for many months, until finally Captain Newport pilots us through the Virginia capes, and the long, hard voyage is ended on April 26, 1607, when we disembark on a sandy spit of land and name the spot Cape Henry. Here we rest while the sealed orders of the London Company are opened and we learn that we are to settle much further inland. We board the vessel again and sail across the Bay to the broad river which we name the James, and whose shores we explore for many a mile seeking dutifully for a suitable place for a settlement. This we think we find at an attractive spot about thirty miles from the mouth of the river, where the water is deep so close to the shore that we can tie our ships to the trees, and here we disembark on a beautiful May day.

“The Jamestown Tower.” Images from book.

A Virginia spring is full of promise, and all is so fair on this charming morning that we do not think to remind our friends that we are disobeying the order which says that we shall not settle in a low or moist place, and we busy ourselves in giving thanks to God in our improvised church under the sailcloth, for our safe arrival.

Now there are trees to be felled and a fort to be built, for yonder, across the narrow neck of land, we often catch glimpses of savages, and though they come among us on friendly errands, we cannot trust them. And so, in a month's time, we build our fort and inside place our houses in straight rows. We are content with very plain houses; indeed they are not much more than huts, but we roof them with marsh grass and pile earth on top to keep them dry. Finally we build us a chapel in the middle of the enclosure, and though it is but a homely thing like a barn and we roof it, as we do our own houses, with grass and earth, in it we can worship God and praise Him for preserving us thus far. But alas! there are dissensions among our leaders; the malaria of the swamps that we forgot to consider attacks many of our number; we have not enough to eat; and we must stop our building and clearing of land to lay one and another in his grave. Before the end of the summer we bury over sixty of our companions and those of us who are left wonder how soon we shall follow.

We live on as we can, having much to do and little strength with which to do it, seeing more English come to join us with many mouths to feed and little enough to put in them. Our leaders fight among themselves and we have no one in command whom we can respect. We have fire after fire which destroys our property and we grow discouraged trying to replace it. In the cold of winter many die from exposure and we pull down even our palisades to use for firewood. Our supplies give out entirely and the people live on roots and herbs until things finally come to such a pass that even dead human bodies are eaten by the most desperate. Of the five hundred people who have come to the Colony but sixty are left, scarcely able to totter about the place. We decide to abandon the settlement and we start back to England, glad to flee from our misery. But before we reach the capes we meet Lord de la Warre, who has come to be our governor. He has plenty of provisions and he takes us back to our ruined settlement to make a fresh start.

New fortifications were now built by the colonists and the houses were repaired. Cedar pews and a walnut altar were placed in the church and every Sunday it was decorated with flowers. A bell was hung in the tower, which not only called the people to church, but notified them when to begin and stop work. Instead of the system of communism which had prevailed the colonists were given land of their own and were obliged to cultivate it. Industry and thrift began to prevail and a repetition of the famine became well-nigh impossible. New settlers arrived and the Colony began to expand.

By 1619 two thousand persons were living in Virginia and they called for self-government, being tired of the tyranny of royal governors. Governor Yeardley issued writs for the election of a General Assembly and the first legislative body in America met in the Jamestown church in July of that year. Just after this meeting, in curious juxtaposition, came the first cargo of Negro slaves; and it was in this year also that there arrived from England a shipload of English maidens as wives for the colonists. Each young woman was free to exercise her choice, but no suitor who met with approval could take his bride unless able to pay the cost of her voyage—one hundred and twenty pounds of tobacco. Thus one year saw in the infant colony the establishment of the home, of a free representative government, and of the institution of slavery.

With the beginning of the culture of tobacco and the expansion of the Colony, Jamestown came to be chiefly a place for the assembling of the legislature and for holding court. A courthouse was built and in this the House of Burgesses met. At such times the little village almost earned its title of town, but the permanent population after 1623 was only about one hundred persons, who lived in brick houses of fair size and style. The first brick church, whose ruined tower is today the chief relic of old Jamestown, was built in 1639. It was a very plain and unpretentious chapel, rectangular in shape with a high-pitched roof.

The aisles were paved with brick and the chancel with tiles. All attempts to increase the size of the town failed and after being destroyed three times by fire, the second time during Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, it was never rebuilt. The climate remained unhealthy and the conviction gradually grew that it would be wise to remove the capital to a more salubrious situation. This was found in Middle Plantation, now Williamsburg, which was made the capital of Virginia in 1698. By 1700 the removal was complete, so that for over two hundred years there has been no town on Jamestown Island.

Since the island was abandoned the river has done its best to obliterate all traces of the "Cradle of the Republic." Its work has at last, however, been interfered with, and patriotic women, under the name of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, have taken steps to rescue from oblivion this "first American metropolis." It was not until 1900, however, after fifty or sixty acres of the island, including the sites of the first landing place and the first and second forts, together with a part of the earliest settlement, had been worn away by the unrestrained action of the water, that this society succeeded in inducing the Government to build a sea wall to prevent further encroachments by the river. This was begun in 1901 and finished in 1905. Outside of this breakwater, two hundred and ninety feet from the shore, stands a lone cypress tree which in 1846 stood on the shore above high water mark.

One who wishes to make a pilgrimage to Jamestown now may follow in the wake of Captain Newport's little vessels, across Hampton Roads, full of historic memories, not only of Colonial times but also of events connected with the great wars of our history; past Newport News at the mouth of the James; and up the river which, could it speak, would have many a pathetic or romantic tale to tell. The names of the places on either bank bring back crowding memories of events of early Colonial days. On Lower Chippoke's Creek on the south side stands "Bacon's Castle," which, though not visible from the river, is one of the most interesting houses in Virginia. It was fortified by Bacon's friends during his rebellion. Further on are Basse's Choice, Pace's Pains, Archer's Hope, Martin's Hundred, and many other places that perpetuate the names of early settlers and which were represented in the General Assembly. Jamestown had reason to be grateful to the owner of the plantation of Pace's Pains, for it was he who saved the capital in the massacre of 1622, a converted Indian of his household having revealed the plot against the settlers.

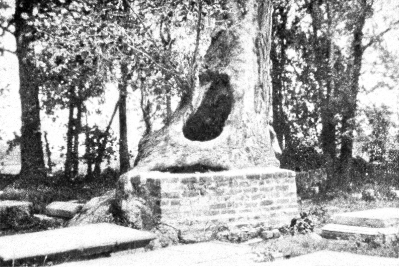

The Jamestown Graveyard.

On landing at Jamestown Island we give ourselves up to the task of rebuilding and repeopling the little town which speaks so eloquently to every American citizen. Turning to the left, for there the tower beckons, we enter the church enclosure. Here are the foundation walls of three of the five Jamestown churches and we examine with reverent interest the inner line of bricks, which we are told supported the wooden walls of the third Colonial church, the one in which met the first General Assembly of Virginia. We picture the governor, the deputy governor, the council, and the twenty-two Burgesses walking in dignified procession up the narrow aisle of the little church, as with stern, serious faces they proceed to transact their important business—a different scene indeed from the squalor and misery that filled the little village only nine years before when Lord de la Warre saved the Colony. Was it here, we wonder, that Pocahontas was baptized and here that she was married? Alas! we learn that the little chapel which witnessed these scenes in the life of the Indian maiden who gave a touch of romance to the rude pioneer town, was inside the palisaded fort now buried under the restless waves of the James. It was just yonder, a stone's throw; while still further out in the water is hidden in the sand of the river bottom the spot on which the Jamestown settlers stepped from their ships. No Plymouth Rock this to withstand forever the action of the waves!

But let us turn again to the foundation walls and the pavements of the churches. Here are the tiles in the chancel of the wooden church and above them the two sets belonging to the two brick churches built on the same foundations. The tower was too massive to be destroyed when the town was fired in Bacon's Rebellion and still gives proof of its age in the "bonded" English brick of which it is made and in the loopholes near its top which indicate that it was used for defense from the Indians before Opechancanough removed that danger by his death.

The worshipers who were wont to gather in these two churches now rest in the ancient graveyard outside. Here lie Dr. James Blair, "Commissary of Virginia and sometime minister of this parish," and his wife, Sarah, a daughter of Colonel Benjamin Harrison. A young sycamore starting between their tombstones carried with it, in the strength of its young life, a portion of Mrs. Blair's tombstone to the height of ten feet. This was accidentally released in 1895 and the tree has nearly closed the cavity, growing meanwhile to an enormous height and shading the whole graveyard. How typical of the gigantic growth of the infant republic born here! All about the old graveyard lie ancient stones, many of them in fragments, and some with their inscriptions quite indecipherable; beyond the enclosure, on the bank of the river, have been found human skeletons lying in such positions as to indicate that the graveyard once extended to the James. We are told that the present lot is about one-third the size of the original, and when we think of the thousands who perished at Jamestown in the early days we are not surprised that human remains have been found in nearly every part of the island.

Virginians have at length awakened to a realizing sense of the importance of preserving what remains of our first settlement. The ancient foundations of the town are being uncovered and every possible effort is being made to keep in good condition what is left of the sacred objects in the church enclosure. So far as possible the tombstones have been mended and the inscriptions made more legible, further vandalism being prevented by a caretaker who lives on the island.

Leaving the graveyard we walk thoughtfully past the earthworks of 1861, now grassgrown and forming part of a shady park peopled with mocking-birds and cardinals. Beyond, we come to the "third ridge" where recent excavations have laid bare the foundations of a row of houses, one of them being the State House in front of which Bacon drew up his soldiers and demanded his commission of Sir William Berkeley. The next one belonged to Colonel Philip Ludwell under whose direction the town was rebuilt after Bacon's Rebellion. As the excavations proceed it will be possible to picture the town as it looked during its last days.

No less than four monuments will be erected on Jamestown Island during the summer of 1907. Perhaps the most imposing will be the marble shaft erected by the Government to mark the scene of the nation's birth. Near it will be another shaft in memory of the first House of Burgesses, built by the Norfolk branch of the A. P. V. A. A bronze monument to Captain John Smith is to be erected on a terrace commanding a view of the river and near the monument to Pocahontas, the gift of the Pocahontas Memorial Association. Over the foundations of the brick churches the Colonial Dames of America have built a church as nearly as possible like the brick one erected in 1639. It contains many tablets, among them one to Rev. Robert Hunt, the first English minister in America. This church was presented to the A. P. V. A. on May 11, 1907. On May 13 the three hundredth anniversary of the landing at Jamestown was celebrated with appropriate ceremonies, Ambassador Bruce of England making the principal address.

Davis, J. E. Round About Jamestown: Historical Sketches of the Lower Virginia Peninsula. 1907.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.