Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

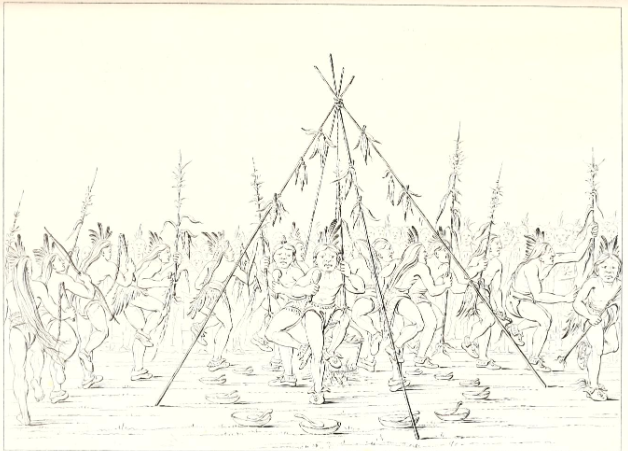

Corn Dance of the Minatarees from The Boy's Catlin by George Catlin, 1928.

The Minatarees, or people of the willows, is a small tribe occupying three villages on the river Knife, which meanders through a lovely prairie into the Missouri. The Minatarees are undoubtedly a part of the Crow tribe, which they resemble in appearance and stature, and from which they were doubtless run off by a war party. At present they are part of the Mandan confederacy, whose wigwams and many of whose customs they have adopted. Although scarcely a man in the tribe can speak Mandan, the Mandans can speak the tongue of the Minatarees, who, by the way, are called by the French traders Gros Ventres.

Their chief sachem, whose guest I am, is a patriarchal man named Eeh-tohk-pah-shee-pee-shah (the black moccasin), who claims more than a hundred snows.

His voice and sight are nearly gone, but his gestures are still energetic and youthful. I have been treated in the kindest manner by this old chief, and have painted his portrait seated on the floor of his wigwam smoking his pipe, a beautiful Crow robe thrown around him, and his hair wound in the form of a cone on the top of his head and fastened by a wooden pin.

As I painted he related to me some of the extraordinary events of his life. He distinctly recalls Lewis and Clarke, who have told how kindly they were treated by this chief. He inquired earnestly for Red Hair and Long Knife, as he called them. I told him that Long Knife had long been dead, but that Red Hair lived in St. Louis and would be glad to hear of him. This pleased him greatly.

I have also painted his son, the Red Thunder, who is one of the most desperate of the Minatarees, who are a warlike people, unlike their neighbors the Mandans. He was painted in his war-dress; that is, he was almost naked, and his body so profusely daubed with red and black paint that it was almost disguised. This is the custom of all Indian warriors, the chief only pluming himself to lead his band and form a conspicuous target for the enemy.

The women of this tribe are unusually good-looking, voluptuous, and free with their bewitching smiles. But I have only been able to get one to consent to be painted, and she was compelled to stand for her portrait by her relatives, who were of the family of the old chief. All the while she modestly urged that “she was not pretty enough to be painted and her picture would be laughed at.” She wore a beautiful costume of the skin of the mountain-sheep, handsomely embroidered with quills and beads, and even if she were not comely, the beauty of her name, Seet-se-be-a (the mid-day sun), would make up for it.

The only places where I find I can write is under the shade of some remote tree, or in my bed, where I now am, lying on sacking of buffalo hide, and surrounded by curtains made from the skins of the elk or buffalo. Meanwhile the roar and unintelligible din of savage conviviality is going on under the same roof. There are other distinguished guests here besides myself. Two Crow chiefs are visiting Black Moccasin in return for a visit made the Crows by several Minatarees.

I have already said that no people present a more picturesque and thrilling appearance than the Crows in all their plumes and trappings in a war parade or sham fight.

From among these showy fellows, who have been entertaining us and pleasing themselves with their extraordinary feats of horsemanship, I have selected one of the most conspicuous, and transferred him and his horse, with arms and trappings, as faithfully as I could, to the canvas, for the information of the world, who will learn vastly more from lines and colors than they could from oral or written delineations.

I have painted him as he sat for me, balanced on his leaping wild horse, with his shield and quiver slung on his back and his long lance decorated with the eagle’s quills trailed in his right hand. His shirt and his leggings and moccasins were of the mountain-goat skins, beautifully dressed, and their seams everywhere fringed with a profusion of scalp-locks taken from the heads of his enemies slain in battle. His long hair, which reached almost to the ground while he was standing on his feet, was now lifted in the air and floating in black waves over the hips of his leaping charger. On his head and over his shining black locks he wore a magnificent crest or head-dress made of the quills of the war-eagle and ermine-skins. On his horse’s head also was another of equal beauty and precisely the same in pattern and material. Added to these ornaments there were yet many others which contributed to his picturesque appearance, and among them a beautiful netting of various colors that completely covered and almost obscured the horse’s head and neck, and extended over its back and its hips, where it terminated in a most extravagant and magnificent crupper, embossed and fringed with rows of beautiful shells and porcupine quills of various colors.

With all these pictuesque trappings about him, with a noble figure and the stamp of a wild gentleman on his face, he leaned gracefully forward, his long locks and fringes floating in the wind, sending forth startling though smothered yelps in unison with the leaps of his wild horse. He was clearly pleased at displaying in this manner the extraordinary skill in the managment of his horse, as well as the graceful motion of his weapons as he brandished them in the air, and of his ornaments as they floated in the wind.

These people raise an abundance of corn or maize, and it is my good fortune to visit them in the season of their festivities, which annually take place when the ears of corn are of the proper size for eating. The green corn is considered a great luxury by all those tribes who cultivate it, and is ready for eating as soon as the ear is of full size and the kernels are expanded to their full growth but are yet soft and pulpy. In this green state of the corn it is boiled and dealt out in great profusion to the whole tribe, who feast and surfeit upon it while it lasts, rendering thanks to the Great Spirit for the return of this joyful season, which they do by making sacrifices, by dancing, and singing songs of thanksgiving. This joyful occasion is one valued alike, and conducted in a similar manner, by most of the tribes who raise the corn, however remote they may be from each other. It lasts but for a week or ten days, being limited to the longest term that the corn remains in this tender and palatable state, during which time all hunting and all war excursions and all other avocations are positively dispensed with, and all join in the most excessive indulgence of gluttony and conviviality that can possibly be conceived. The fields of corn are generally pretty well stripped during this excess, and the poor improvident Indian thanks the Great Spirit for the indulgence he has had, and is satisfied to ripen merely the few ears that are necessary for his next year’s planting, without reproaching himself for his wanton lavishness, which has laid waste his fine fields and robbed him of the golden harvest which might have gladdened his heart, with those of his wife and little children, through the cold and dreariness of winter.

The most remarkable feature of these joyous occasions is the green-corn dance, which is always given as preparatory to the feast and by most of the tribes in the following manner:

At the usual season, and the time when from the outward appearance of the stalks and ears of the corn it is supposed to be nearly ready for use, several of the old women, who are the owners of fields or patches of corn (for such are the proprietors and cultivators of all crops in Indian countries, the men never turning their hands to such degrading occupations), are delegated by the medicine-men to look at the corn fields every morning at sunrise, and bring into the council-house, where the kettle is ready, several ears of corn, the husks of which the women are not allowed to break open or even to peep through. The women then are from day to day discharged and the doctors left to decide, until, from repeated examinations, they come to the decision that it will do, when they despatch runners or criers, announcing to every part of the village or tribe that the Great Spirit has been kind to them, and that they must all meet on the next day to return thanks for his goodness; that all must empty their stomachs and prepare for the feast that is approaching.

On the day appointed by the doctors the villagers are all assembled, and in the midst of the group a kettle is hung over a fire and filled with the green corn, which is well boiled, to be given to the Great Spirit as a sacrifice necessary to be made before any one can indulge the cravings of his appetite. While this first kettleful is boiling, four medicine-men, with a stalk of the corn in one hand and a rattle (she-she-quoi) in the other, and with their bodies painted with white clay, dance around the kettle, chanting a song of thanksgiving to the Great Spirit to whom the offering is to be made. At the same time a number of warriors are dancing around in a more extended circle, with stalks of the corn in their hands, and joining also in the song of thanksgiving, while the villagers are all assembled and looking on. During this scene there is an arrangement of wooden bowls laid upon the ground, in which the feast is to be dealt out, each one using a spoon made of the buffalo or mountain-sheep’s horn.

In this wise the dance continues until the doctors decide that the corn is sufficiently boiled; it then stops for a few moments, and again assumes a different form and a different song while the doctors are placing the ears on a little scaffold of sticks, which they erect immediately over the fire, where it is entirely consumed as they join again in the dance around it.

The fire is then removed, and with it the ashes, which together are buried in the ground, and new fire is originated, on the same spot where the old one was, by friction. This is done with desperate and painful exertion by three men seated on the ground, facing each other and violently drilling the end of a stick into a hard block of wood by rolling it between the hands, each one catching it in turn from the others without allowing the motion to stop until smoke, and at last a spark of fire, is seen and caught in a piece of spunk, when there is great rejoicing in the crowd. With this a fire is kindled and the kettle of corn again boiled for the feast at which the chiefs, doctors, and warriors are seated. After this permission is given to the whole tribe to indulge, which they do to excess and until the corn is too hard for mastication.

Having heard that I was “great medicine,” a party of young men, accompanied by some of the chiefs and doctors, came in a formal body to present a grievance which it was hoped I might remedy. After several profound speeches, it appeared that a few years ago an unknown small animal was seen stealing slyly among the pots and kettles of one of the chief’s wigwams. It was described as having the size of a ground-squirrel, but with a long, round tail, and was regarded as such “great medicine” that hundreds came to see it. On one occasion this little animal was seen devouring a deer-mouse, which is very destructive to the wearing apparel of the Indians. It was at once decided that the little defeature had been sent by the Great Spirit to protect their clothing, and a council issued a solemn decree for its preservation. Having been thus preserved, the numbers of these little animals, which my man Batiste calls Monsieur Ratipon, had so increased that the wigwams were now infested by rats, the caches that contained the corn and other food were robbed, and the very pavements of their wigwams were so vaulted and sapped that they were falling in. The object of this meeting was to see if I could not relieve them of this public calamity. I could only assure them of my deep regret, but there was too much medicine in the thing for me to undertake it.

As I wished to visit another Minataree village on the other side of the river Knife, the old chief gave directions to one of the numerous women of his household, who took upon her head a skin canoe, called in this country a bull boat, made in the form of a tub, of buffalo’s hide, and, carrying it to the water’s edge, made signs for the three of us to get in. When we were seated flat in the bottom, with scarcely room to adjust our legs and our feet (as we sat necessarily facing each other), she stepped before the boat, and, pulling it along, waded toward the deeper water, with her back toward us, carefully with the other hand attending to her dress. This seemed to be but a light slip, floating upon the surface until the water was above her waist, when it was instantly turned off, over her head, and thrown ashore, and she boldly plunged forward, swimming and drawing the boat with one hand, which she did with apparent ease. In this manner we were conveyed to the middle of the stream, where we were soon surrounded by a dozen or more beautiful girls, from twelve to fifteen and eighteen years of age, who were at that time bathing on the opposite shore.

They all swam in a bold and graceful manner, and as confidently as so many otters or beavers, as they gathered around us, with their long black hair floating about on the water, while their faces were glowing with jokes and fun, which they were cracking about us, and which we could not understand.

In the midst of this delightful little aquatic group we three sat in our little skin-bound tub (like the “three wise men of Gotham who went to sea in a bowl,’’ etc.), floating along down the current, losing sight and all thoughts of the shore, which was equidistant from us on either side, whilst we were amusing ourselves with the playfulness of these dear little creatures who were floatingabout under the clear blue water, catching their hands onto the sides of our boat, occasionally raising one-half of their bodies out of the water, and sinking again, like so many mermaids.

In the midst of this bewildering and tantalizing entertainment, in which poor Batiste and Bogard, as well as myself, were all taking infinite pleasure, and which we supposed was all intended for our especial amusement, we found ourselves suddenly in the delightful dilemma of floating down the current in the middle of the river, and of being turned round and round, to the excessive amusement of the villagers, who were laughing at us from the shore, as well as these little tyros, whose delicate hands were besetting our tub on all sides, and for an escape from whom, or for fending off, we had neither an oar nor anything else that we could wield in self-defence or for self-preservation. In this awkward predicament our feelings of excessive admiration were immediately changed to those of exceeding vexation as we now learned that they had peremptorily discharged from her occupation our fair conductress, who had undertaken to ferry us safely across the river, and had also very ingeniously laid their plans, of which we had been ignorant until the present moment, to extort from us in this way some little evidences of our liberality, which, in fact, it was impossible to refuse them, after so liberal and bewitching an exhibition on their part, as well as from the imperative obligation which the awkwardness of our situation had laid us under.

I had some awls in my pockets, which I presented to them, and also a few strings of beautiful beads, which I placed over their delicate necks as they raised them out of the water by the side of our boat. They all then joined in conducting our craft to the shore, by swimming by the sides of and behind it, pushing it along in the direction where they designed to land it, until the water became so shallow that their feet were upon the bottom, when they waded along with great coyness, dragging us toward the shore so long as their bodies, in a crouching position, could possibly be half concealed under the water. They then gave our boat the last push for the shore, and, raising a loud and exulting laugh, plunged back again into the river, leaving us the only alternative of sitting still where we were or of stepping out into the water at half-leg deep and of wading to the shore, which we at once did, and soon escaped from the view of our little tormentors, and the numerous lookers-on, on our way to the upper village which I have before mentioned.

Here I was very politely treated by Yellow Moccasin, quite an old man, and who seemed to be chief of this band or family, constituting their little community of thirty or forty lodges, averaging perhaps twenty persons to each. I was feasted in this man’s lodge, and afterward invited to accompany him and several others to a beautiful prairie, a mile or so above the village, where the young men and young women of this town, and many from the village below, had assembled for their amusements, the chief of which seemed to be that of racing their horses. In the midst of these scenes, after I had been for some time a looker-on, and had felt some considerable degree of sympathy for a fine-looking young fellow, whose horse had been twice beaten on the course, and whose losses had been considerable—for which his sister, a very modest and pretty girl, was most piteously howling and crying—I selected and brought forward an ordinary-looking pony, that was evidently too fat and too sleek to run against his fine-limbed little horse that had disappointed his high hopes; and I began to comment extravagantly upon its muscle, etc., when I discovered him evidently cheering up with the hope of getting me and my pony onto the turf with him, for which he soon made me a proposition. I, having lauded the limbs of my little nag too much to “back out,” agreed to run a short race with him of half a mile, for three yards of scarlet cloth, a knife, and half a dozen strings of beads, which I was willing to stake against a handsome pair of leggings, which he was wearing at the time. The greatest imaginable excitement was now raised among the crowd by this arrangement, to see a white man preparing to run with an Indian jockey, and that with a scrub of a pony in whose powers of running no Indian had the least confidence.

Yet there was no one in the crowd who dared to take up the several other little bets I was willing to tender (merely for their amusement and for their final exultation), owing, undoubtedly, to the bold and confident manner in which I had ventured on the merits of this little horse, which the tribe had all overlooked and needs must have some medicine about it.

So far was this panic carried that even my champion was ready to withdraw, but his friends encouraged him, and at length we galloped our horses to the other end of the course, accompanied by a number of horsemen to see the "set-off.” Here a condition was named to me that I had not anticipated. In all the races of this day the riders were to be naked and to ride a naked horse. I found that remonstrance availed little, and as I had volunteered to ride to gratify them it seemed wise to comply. Accordingly I took off my clothes, straddled the naked back of my round and glossy little pony, by the side of my competitor, who was also mounted and stripped to the skin eager for the start.

Can any one imagine that a man in middle life could be so suddenly transported back to infancy and breathe the air of naked, untasted liberty. If not, disrobe, and fancy yourself, as I was, naked, with my trembling little steed under me, and the cool breeze ready to close and embrace me, as it did the next moment when we “were off.” Though my little Pegasus seemed to dart through the clouds, and I to be wafted on the wings of Mercury, yet my red adversary soon left me far behind. No longer a competitor, I wheeled to the left and made the circuit of the prairie back to the starting-point, much to the satisfaction of the jockeys, but greatly to the disappointment of the women and children, who had come out in throngs to witness the “coming out” of the white medicine-man.

I clothed myself rapidly and came back acknowledging, my defeat and the superior skill of my competitor, as well as the wonderful muscle of his little charger, which pleased him greatly. His sister’s disappointment I soon turned to joy by giving her a fine scarlet robe and a profusion of varicolored beads, which she was soon parading on her copper-colored neck.

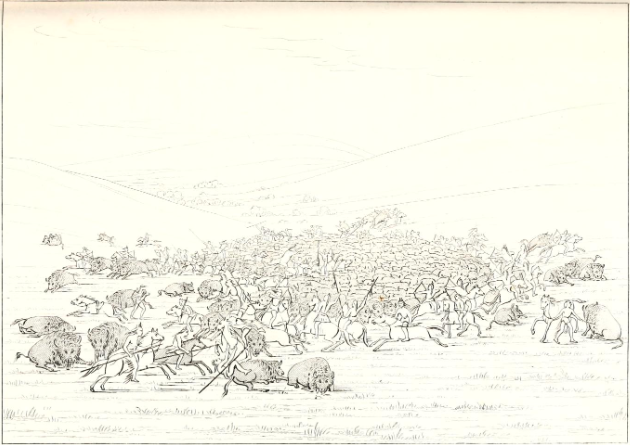

The Minatarees as well as the Mandans had suffered for some months for want of meat. It was feared that the buffalo herds were emigrating and actual starvation might ensue. Suddenly one morning a herd was sighted, and a hundred or more young men jumped on their horses, with their weapons, and made for the prairie. The chief offered me one of his horses and said I had better go and see an interesting sight. I took my pencil and sketch-book and took my position in the rear, where I could witness every manoeuvre. The plan of attack in this country is called a “surround.” The hunters were all mounted on their “buffalo horses,” and armed with bows, arrows, and long lances.

Dividing into two columns and taking opposite directions, they drew themselves gradually around the herd a mile or more distant from it, forming a circle of horsemen at equal distances apart, who gradually closed in upon them with a moderate pace, at a signal given. The unsuspecting herd at length “got the wind” of the approaching enemy, and fled in a mass in the greatest confusion. To the point where they were aiming to cross the line the horsemen were seen at full speed, gathering and forming in a column, brandishing their weapons, and yelling in the most frightful manner, by which means they turned the black and rushing mass, which moved off in an opposite direction, where they were again met and foiled in a similar manner and wheeled back in utter confusion. By this time the horsemen had closed in from all directions, forming a continuous line around them, while the poor affrighted animals were eddying about in a crowded and confused mass, hooking and climbing upon each other, when the work of death commenced. I had ridden up in the rear and occupied an elevated position at a few rods’ distance, from which I could (like the general of a battle-field) survey from my horse’s back the nature and the progress of the grand melee, but (unlike him) without the power of issuing a command or in any way directing its issue.

In this grand turmoil a cloud of dust was soon raised, obscuring the throng where the hunters were galloping their horses around and driving the whizzing arrows or their long lances to the hearts of these noble animals. These, in many instances becoming infuriated with deadly wounds in their sides, plunged forward at the sides of their assailants’ horses, sometimes goring them to death at a lunge and putting their dismounted riders to flight for their lives. Sometimes their dense crowd was opened, and the blinded horsemen, too intent on their prey amid the cloud of dust, were hemmed and wedged in amid the crowding beasts, over whose backs they were obliged to leap for security, leaving their horses to the fate that might await them in the results of this wild and desperate war.

Many were the bulls that turned upon their assailants and met them with desperate resistance, and many were the warriors who were dismounted and saved themselves by the superior muscles of their legs; some, who were closely pursued by the bulls, wheeled suddenly around, and, snatching the part of a buffalo-robe from around their waists, threw it over the horns and the eyes of the infuriated beast, and darting by its side drove the arrow or the lance to its heart. Others suddenly dashed off upon the prairies by the side of the affrighted animals which had escaped from the throng, and, closely escorting them for a few rods, brought down their hearts’ blood in streams and their huge carcasses upon the green and enamelled turf.

I had sat in trembling silence upon my horse and witnessed this extraordinary scene, which allowed not one of these animals to escape out of my sight. Many plunged off upon the prairie for a distance, but were overtaken and killed; and although I could not distinctly estimate the number that were slain, yet I am sure that some hundreds of these noble animals fell in this grand melee,

The scene after the battle was over was novel and curious in the extreme; the hunters were moving about among the dead and dying animals, leading their horses by their halters, and claiming their victims by the private marks upon the arrows, which they were drawing from the wounds in the animals’ sides.

The poor affrighted creatures that had occasionally dashed through the ranks of their enemy and sought safety in flight upon the prairie (and in some instances had undoubtedly gained it), I saw stand awhile, looking back when they turned, and, as if bent on their own destruction, retrace their steps and mingle themselves and their deaths with those of the dying throng. Others had fled to a distance on the prairies, and for want of company, of friends or of foes, had stood and gazed on till the battle-scene was over, seemingly taking pains to stay and hold their lives in readiness for their destroyers until the general destruction was over, to whose weapons they fell easy victims—making the slaughter complete.

After this scene, and after arrows had been claimed and recovered, a general council was held, when all hands were seated on the ground and a few pipes smoked, after which all mounted their horses and rode back to the village.

Several of the warriors were sent to the chief, to inform him of their success; and the same intelligence was soon communicated by little squads to every family in the village, and preparations were at once made for securing the meat. For this purpose some hundreds of women and children, to whose lot fall all the drudgeries of Indian life, started out upon the trail which led them to the battle-field, where they spent the day in skinning the animals and cutting up the meat, which was mostly brought into the villages on their backs, as they tugged and sweated under their enormous and cruel loads.

I rode out to see this curious scene, and I regret exceedingly that I kept no memorandum of it in my sketch-book. Amid the throng of women and children that had been assembled, and all of whom seemed busily at work, were many superannuated and disabled nags, which they had brought out to assist in carrying in the meat, and at least one thousand semi-loup dogs and whelps, whose keen appetites and sagacity had brought them out to claim their share of this abundant and sumptuous supply.

I stayed and inspected this curious group for an hour or more, during which time I was almost continually amused by the clamorous contentions that arose and generally ended in desperate combats, both among dogs and women, who seemed alike tenacious of their rights and disposed to settle their claims tooth and nail.

When I had seen enough of this I withdrew to the top of a beautiful prairie bluff a mile or two from the scene, and overlooking the route through the undulating green fields, watched the continuous passing of women, dogs, and horses carrying home their heavy burdens to the village, resembling from afar nothing so much as a busy community of ants sacking and carrying away the treasures of a cupboard or the sweets of a sugar-bowl.

Catlin, George. The Boy's Catlin. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1928.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.