Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Reminiscences of Pioneer Life by Robert Latta, 1912.

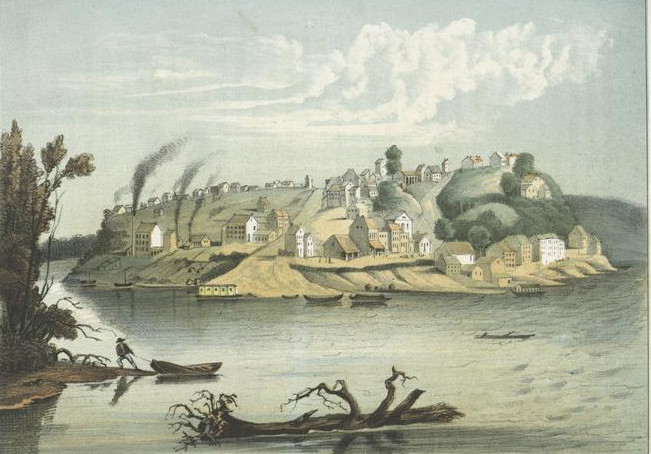

On the fifteenth day of June, 1848, a slow-going stern-wheel steamboat, the Red Wing, with much puffing of steam and groaning of her ponderous engines, was pushing her way up against the current of the upper Mississippi River. Dense forests lined the banks and stretched away beyond the summit of the river bluffs. Not a sign to indicate that man had ever penetrated the somber shade.

When the Red Wing, a week before, steamed away from the wharf at Saint Louis, she was loaded with boxes, bales, barrels, and bundles, cows, oxen, horses, and sheep; and on her hurricane deck were wagons, plows, and carts, crates of pigs and coops of chickens. Like Noah's Ark, two and two of every kind. And the deck was crowded with men, women, and children and the faithful old dog; a crowd of immigrants, going forth to seek out and build for themselves homes on the western frontier.

On arriving at Keokuk, a large number went ashore. From this point they will go out along diverging ways, like spokes from a half-hub, and be scattered among the hills and the valleys, the forests and the prairies of the western borderland. After leaving Keokuk, stops were made at many points and others were set ashore. And on this morning but one family remained on board. This family consisted of husband and wife and their seven children. The eldest, Jim, was a lad of fourteen years; the youngest, a wee curly-headed baby girl in the Mother's arms. The second round (from the top) in the family ladder was a small, sturdy, freckle-faced boy (called "Freck" for short) of twelve years. And this same Freck has now entered upon the task of entertaining the reader.

For three weeks this family had been traveling by steamboat, having changed boats four times. Usually the blare of the whistle and the clang of the bell disturbed not their repose; but now, however, when the whistle sent out the three long-drawn-out "Whoo! whoo! whoo!” which went echoing far out into the dark, gloomy woods and died away in a moan, and the great bell on the hurricane deck pealed out "Ding-dong! Ding-dong! Ding-dong!" the signal for landing, a tremor took hold of them; for the mate shouted, "Port Huron! Get ready to go ashore." Port Huron was the end of the long journey by steamboat.

The little bells hanging over the engines said to the engineers, "Slow up!" And the engineers whirled the throttles, and the pilot whirled the wheel, and the Red Wing pointed her prow toward the western shore and crept up and poked her nose against the soft bank; and the line was made fast around a tree, and the gangplank run out; and the little group was quickly pushed ashore and their stuff piled on the ground.

Again the great bell tolled off, "Ding-dong! Ding-dong! Ding-dong!" which said, "Let go the line! Let go the line! Let go the line!" And the little engine bells said, "Back her off!" And the long walking-beams, reaching away back and grasping the cranks on the wheel-shaft, began to move, and the Red Wing backed away from the shore. And the Iittle bells called, "Go ahead!" And the engineers adjusted the cams, and the engines reversed their motion, and the Red Wing began to move slowly up the river.

And the little group, with the mile-wide river on the one side and the untrodden forest on the other side, and some cord-wood on the bank, and a cabin back in the woods, but not a living thing in sight, stood on the western shore of the Mississippi River and watched their home pass around a bend out of sight.

And the mental picture which they had painted on the canvas of the brain (of a home in the romantic wildwood on the western frontier, which had cheered them on the way and which they were so eager to reach) gave place to a feeling of lonely depression; for the picturesque fanciful wildwood and the real wildwood were quite different.

Hearing footfalls, they looked around, and saw a tall, bony man, a true type of the frontiersman, clad in home-spun, with his sleeves rolled to the armpits and his shirt open at the throat; and with a hearty "How-dy, stranger?" he seated himself on a box and began to ask the usual questions. This man was the woodyard-keeper. For in those days men would go into the woods and chop cordwood in the winter, to be sold to the steamboats, and one of them would look after the sales. The land was all “Congress land,” now called “Government land.”

The Father had a brother living in the region of Port Huron. This was why he landed here. "Yes, I know your brother," said Mr. W; "we all call him 'Uncle Jimmy.’ He lives on Indian Creek, fifteen miles out. He was one of the first settlers in this country came in before the Indians were moved; and he has done much to subdue the wilderness, by opening new farms and building mills. And he has the same number of sons and daughters that old Jacob had."

It was decided that Jim and Freck should go in search of Uncle Jimmy and a team. And Mr. W remarked: "Boys, it is only fifteen miles, and you will find a trail leading from the wood-ricks to the top of the bluffs; there take the left-hand road, and you will soon come out onto the prairie." But the boys knew not the meaning of "prairie," for they were raised in the big woods.

Having heard wild stories of bears and wolves and panthers roaming the woods in the West, the boys considered it wise to take a gun along. And the old smooth-bore was carefully loaded by the Father. And the boys crossed the river bottom and were going up the hill, when they wheeled around and started down the hill as fast as their feet could carry them. The panic subsiding, they retraced their steps. "Will it still be there? Yes; there it is." A monster snake, stretching clear across the road, his head resting on the little bank and his dark and yellow spots glistening in the sun. Jim crept up behind a big stump and, placing the gun thereon, took deliberate aim and fired, blowing the top of the snake's head off.

Because of the excitement in landing, the boys had eaten no breakfast, and in the afternoon the hand of hunger began to pinch them and the old smooth-bore increased in heaviness with each mile; the boys carrying it time about, or each grasping an end. And just as the sun was shutting his door, we came to Uncle Jimmy's cabin in Indian Creek Grove, and we made ourselves and our errand known, and were given a friendly greeting. And just as the sun was showing his bright face above the eastern hills we were merrily trotting along the road to Port Huron. And in the evening we stopped before the gate at Uncle Jimmy's cabin, but Uncle Jimmy was at the Yellow Spring Mills, in Des Moines County.

And the next morning the Father started on foot to see his brother, whom he had not seen for thirty years, and to arrange for work; for his money was nearly all gone, and he would not eat the bread of idleness. And the Father returned, and we were to go to the Yellow Spring Mills. Frank could not spare a span of horses, and a couple of yoke of young oxen were yoked to the wagon, and Frank took up the whip, saying, "I will drive out through the woods and see that the steers go off all right."

But they had not gone far until they crowded Frank out of the road and bounded into a gallop and went thundering down the road; and the wheels striking the stumps, the wagon went spinning along on two wheels, first on one side and then on the other side. And the Mother and the children, like balls, were tossed from side to side; the Mother holding the wee curly-headed baby girl close to her breast. At the point where the road came out onto the prairie there was a cabin, and the people, hearing the rattle, ran out and stopped the frantic beasts, where they stood with beating sides and wild-rolling eyes. The Mother sprang out and snatched her children out, and being wholly overcome, she sank to the ground and burst into hysterical crying, still holding the wee curly-headed baby girl close to her bosom.

The young steers were unhitched and a yoke of steady going oxen was borrowed from Sam, the Father took up the whip, and we started off to the southward.

That night was the beginning of our camping-out. Soon the camp-fire was blazing, and the perfume of frying bacon and boiling coffee floated away on the evening air, and the boys were chuck-full of the gladness of the new life. Blankets were spread on the grass, and soon the voices all were hushed and we were sleeping, for the first time, beneath the stars of heaven, on the western frontier.

The next day we crossed the Iowa River on a rope ferry. Old-timers need no explanation of a rope ferry, but to those who have not known nor will ever know a western frontier and the rude and primitive ways I will say that a rope ferry was a simple affair. A strong rope was made fast around a tree near the bank, and the other end was carried across the river and tied to a tree; two short ropes, with grooved pulleys to follow along the big rope, were made fast to the flatboat near each end, and, by a device for the purpose, the bow rope was shortened, placing the boat diagonally across the current, and the water would drive it across.

The city of Wapello, the county seat of Louisa County, a city of five or six cabins, stood on the bank of the river.

In due time we arrived at the Yellow Spring Mills, and in a few hours housekeeping was begun, in a one-room cabin, without window or floor; the cooking was done at the fireplace, and the washing down at the branch.

After allowing the oxen a, day to rest, Jim and Freck were started off to return the oxen. In the afternoon of the first day one of the bow-keys broke, and the bow fell from the yoke, and the off ox walked out of the road; and when we attempted to bring him under the yoke, he kept on feeding and getting farther and farther away. Men working in a near-by field came to our assistance and a new key was fitted, and, thanking our friends, we went on our way.

On our homeward journey the ferryman set us over the river in his canoe, a big log scooped out and pointed off a little at the ends ; it rolled and pitched at each stroke of the oars, and threatened to turn bottom side up but it didn't.

Jim was put to work helping the Father haul wood to the mill with a yoke of black oxen. Freck was given a position in the carding-mill. His duty was to spread the wool evenly on a table over which an endless apron revolved, and sprinkle it with melted grease; the moving apron carried the wool within the reach of the teeth on the revolving cards, and it came out on the other side of the machine in rolls, ready for the spinning-wheel.

Settlers would come for fifty miles, bringing their own and their neighbors' wool, pinned with thorns in old sheets and blankets, and fetching along the required amount of grease in old crocks and coffee-pots. A record was kept of each bundle, and a time set to return for the rolls.

The return home with the rolls was the beginning of a season of activity in the cabins. The spinning-wheels were gotten out and put in order. There were two kinds of spinning-wheels used, the big wheel and the little wheel. The little wheel was the more common. The spinner sat on a stool and turned the wheel with her foot and manipulated the roll with her hands. And the boy who sat night after night and dozed by the smoldering fire, and listened to the "Whirr, whirr, whirr” and the "Buzz, buzz, buzz," will hear the song of his Mothers spinning-wheel while he lives.

Because of its greater capacity, the big wheel was preferred where there were big girls. The spinner walked backward and forward, turning the wheel with a wheel-hook, and drawing out the roll to great length. And backward and forward she tramped, until the puncheons were worn smooth by her bare feet and the great bundles of rolls were converted into thread.

Next came the dyeing, then the weaving, then the making of the garments. Even the thread was manufactured in the cabin home. The thread, and the fine linen, and the tow cloth for hunting-shirts and grain bags came up step by step from the flax-patch, which was planted and pulled, scutched and hackled and spun by the mothers and daughters.

The sewing-machine and the washing-machine were unknown. The washing was done down at the branch, by dipping soft soap with the hand from a gourd hanging on a limb and smearing it on the garments, and rubbing them between the knuckles; while the baby kicked and cooed in a sugar-trough in the shade.

And the everlasting knitting! On looking back, it seems that girls were never too little to knit. And women visiting, riding or walking, plied their knitting on the way.

Robert Ray Latta. Reminiscences of Pioneer Life. F. Hudson, 1912.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.