Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From An American in the Making by Marcus Eli Ravage, 1917.

When I hear all around me the foolish prattle about the new immigration — "the scum of Europe," as it is called — that is invading and making itself master of this country, I cannot help saying to myself that Americans have forgotten America. The native, I must conclude, has, by long familiarity with the rich blessings of his own land, grown forgetful of his high privileges and ceased to grasp the lofty message which America wafts across the seas to all the oppressed of mankind. What, I wonder, do they know of America, who know only America.

The more I think upon the subject the more I become persuaded that the relation of the teacher and the taught as between those who were born and those who came here must be reversed. It is the free American who needs to be instructed by the benighted races in the uplifting word that America speaks to all the world. Only from the humble immigrant, it appears to me, can he learn just what America stands for in the family of nations. The alien must know this, for he alone seems ready to pay the heavy price for his share of America. He, unlike the older inhabitant, does not come into its inheritance by the accident of birth. Before he can become an American he must first be an immigrant.

More than that, back of immigration lies emigration. And to him alone is it given to know the bitter sacrifice and the deep upheaval of the soul that are implied in those two words.

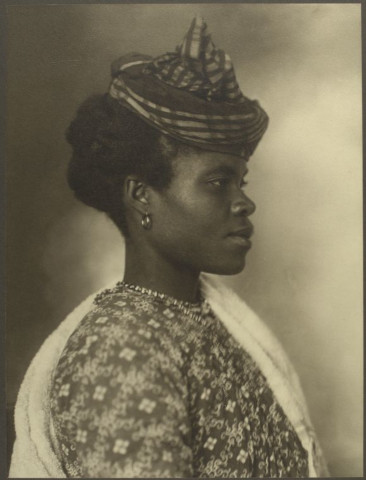

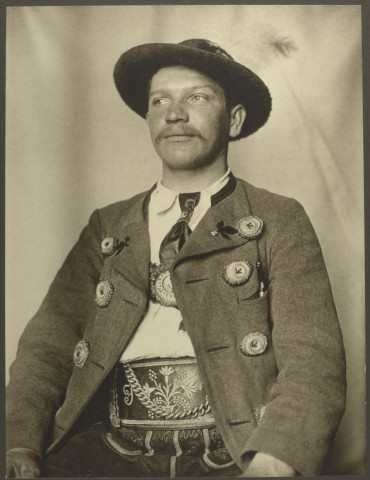

The average American, when he thinks of immigrants at all, thinks, I am afraid, of something rather comical. He thinks of bundles — funny, picturesque bundles of every shape and size and color. The alien himself, in his incredible garb, as he walks off the gang-plank, appears like some sort of an odd, moving bundle. And always he carries more bundles. Later on, in his peculiar, transplanted life, he sells nondescript merchandise in fantastic vehicles, does violence to the American's language, and sits down on the curb to eat fragrant cheese and unimaginable sausages. He is, for certain, a character fit for a farce.

So, I think, you see him, you fortunate ones who have never had to come to America. I am afraid that the pathos and the romance of the story are quite lost on you. Yet both are there as surely as the comedy. No doubt, when you go slumming, you reflect sympathetically on the drudgery and the misery of the immigrant's life. But poverty and hard toil are not tragic things. They indeed are part of the comedy. Tragedy lies seldom on the surface. If you would get a glimpse of the pathos and the romance of readjustment you must try to put yourself in the alien's place. And that you may find hard to do.

Well, try to think of leave-taking — of farewells to home and kindred, in all likelihood never to be seen again; of last looks lingering affectionately on things and places; of ties broken and grown stronger in the breaking. Try to think of the deep upheaval of the human soul, pulled up by the roots from its ancient, precious soil, cast abroad among you here, withering for a space, then slowly finding nourishment in the new soil, and once more thriving — not, indeed, as before — a novel, composite growth. If you can see this you may form some idea of the sadness and the glory of his adventure.

Oh, if I could show you America as we of the oppressed peoples see it! If I could bring home to you even the smallest fraction of this sacrifice and this upheaval, the dreaming and the strife, the agony and the heartache, the endless disappointments, the yearning and the despair — all of which must be ours before we can make a home for our battered spirits in this land of yours. Perhaps, if we be young, we dream of riches and adventure, and if we be grown men we may merely seek a haven for our outraged human souls and a safe retreat for our hungry wives and children. Yet, however aggrieved we may feel toward our native home, we cannot but regard our leaving it as a violent severing of the ties of our life, and look beyond toward our new home as a sort of glorified exile.

So, whether we be young or old, something of ourselves we always leave behind in our hapless, cherished birthplaces. And the heaviest share of our burden inevitably falls on the loved ones that remain when we are gone. We make no illusions for ourselves. Though we may expect wealth, we have no thought of returning. It is farewell forever. We are not setting out on a trip; we are emigrating. Yes, we are emigrating, and there is our experience, our ordeal, in a nutshell. It is the one-way passport for us every time. For we have glimpsed a vision of America, and we start out resolved that, whatever the cost, we shall make her our own. In our heavy-laden hearts we are already Americans. In our own dumb way we have grasped her message to us.

Yes, we immigrants have a real claim on America. Every one of us who did not grow faint-hearted at the start of the battle and has stuck it out has earned a share in America by the ancient right of conquest. We have had to subdue this new home of ours to make it habitable, and in conquering it we have conquered ourselves. We are not what we were when you saw us landing from the Ellis Island ferry. Our own kinsfolk do not know us when they come over. We sometimes hardly know ourselves.

Ravage, Marcus Eli. An American in the Making. Harper & Brothers, 1917.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.