Few nations have produced so many famous scientists as Scotland. Long known for its towering universities, the nation was also one of the first hotbeds of the industrial revolution. It’s no surprise, then, that despite its small size, Scotland has produced more than its fair share of great scientists. These are just a few of the notable Scottish men and women who have shaped our lives and understanding of the world.

John Napier (1550 - 1617)

Before calculators, physicists and mathematicians ran into the problem of simple calculation. People were working with larger numbers than ever before, including exponential squares, cubes, etc. The multiplication needed to solve cutting-edge problems could take enormous amounts of time. John Napier solved this issue through logarithms.

Logarithms, as he called them, express relationships between numbers in a simplified format. Rather than finding that the cube root of 8 is 2 (i.e. 2 x 2 x 2 = 8) by hand, Napier wrote it out as log2 (8) = 3. He then compiled these logarithms in vast lists known as logarithm tables for scholars to reference. These remained in common use until electronic calculators rendered them mostly obsolete. Who knows how many discoveries Napier made possible with his time-saving equations? He is also credited with popularizing the decimal point.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1707 - 1758)

Not to be confused with the first woman to earn a medical degree in America, by the same name, Elizabeth Blackwell was one of the first and most important female illustrators in botany. Her life was a tumultuous one, thanks to the eternal troubles of her husband. Blackwell, hoping to raise funds to release him from debtor’s prison, set to work illustrating a compendium of plants from the Americas, A Curious Herbal. Her husband was eventually executed for an alleged conspiracy against the Crown Prince of Sweden, but Blackwell is more fondly remembered for her contributions to botany and precise illustrations.

James Hutton (1726 - 1797)

The founder of modern geology, Hutton courted religious controversy by proposing that the Earth might be much older than the Bible suggested. He drew his conclusion after extensive travels, observing rock formations wherever he went. Hutton realized that the world around him was the product of millions of years, not thousands, though he couldn’t know how old it really was. He also put forth the idea that Earth was hot at its core, recycling land after it sank into the sea. His views would not be widely accepted for decades after his death, but he is now appreciated as a scientist ahead of his time.

James Watt (1736 - 1819)

The modern, industrial world was largely built on the steam engine of James Watt. Though he did not actually invent the steam engine, his designs dramatically improved its efficiency and potential. His machine gave Britain a head-start in the industrial revolution, paving the way for steam-powered ships and factories and powered by coal lifted from the earth with yet more steam pumps. Though steam power is not as important as it used to be, Watt is remembered through the watt, a standard unit of power.

Lord Kelvin (1824 - 1907)

One of the most influential figures in physics, Sir William Thomson was born in Belfast, Ireland to Scottish parents. His lordly name is memorialized by the Kelvin temperature scale, which extends from absolute zero, the coldest possible temperature, to the theoretical hottest. His work with heat, pressure, and electricity led to the development of the first two laws of thermodynamics. He also contributed to the Atlantic Cable Project, which connected North America to Europe by telegraph cable for the first time in 1858. Overnight, messages could be transmitted across the ocean almost instantly, rather than carried by slow ships.

James Clerk Maxwell (1831 - 1879)

James Clerk Maxwell is another Scottish scientist widely recognized as a pioneering founder of his field. In this case, his major work was in electromagnetism. Through experiments with light, electricity, and magnets, Maxwell came to recognize their close relationship and express them through math. Using this knowledge, he also invented color photography. His work set the stage for the later physics of minds like Albert Einstein, making him one of the most pivotal figures in all of science. Every electrical device today, down to the computer displaying this article, owes a debt to Maxwell.

Alexander Graham Bell (1847 - 1922)

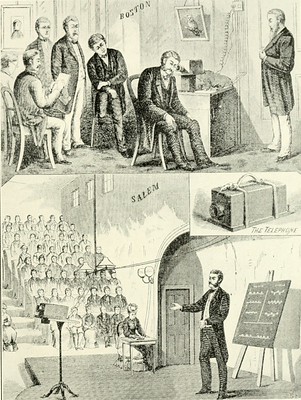

Alexander Graham Bell was a Scottish-born inventor who spent most of his life in Boston, United States. The founder of AT&T, or the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, he is best known for patenting the first telephone. Like the telegraph, the telephone expanded human communication and forever altered human history. Beyond his pioneering invention, he also dedicated his life to tutoring and improving the lives of deaf individuals, including Helen Keller. He is, however, controversial today due to his disapproval of sign language and attitude toward deafness as a societal ill.

Williamina Fleming (1857 - 1911)

Like Alexander Graham Bell, Williamina Fleming was born in Scotland but made most of her discoveries from Boston. A single mother working as a maid, she entered the field of astronomy by chance; her employer, Professor Edward Pickering, hired her on to do clerical work at the Harvard College Observatory. From there, she quickly rose to become one of the most respected astronomers at Harvard. She worked with other female mathematicians and astronomers as part of a large collaborative network, almost unheard of in the 1880s. Among her many contributions to astronomy, she cataloged hundreds of celestial objects, including the famous Horsehead Nebula.

Alexander Fleming (1881 - 1955)

Which scientist has saved the most lives in history? No one can know for sure, but Alexander Fleming ranks somewhere near the top. The discoverer of penicillin opened up the wider world of antibiotics, at a time when even a small infected cut could prove fatal. His breakthrough came in 1928, famously by accident. After leaving a stack of dirty petri dishes while away on vacation, Fleming returned to find that one sample had grown a mold that destroyed Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. “That’s funny,” said Fleming, but he didn’t fully grasp the mass potential of penicillin, and it only entered widespread use by World War II.

John Logie Baird (1888 - 1946)

We’ve seen telegraph cables and telephones, but what about that other major innovation, the television? Scotland played a role in that as well. Specifically, John Logie Baird, who demonstrated the first working television and the first working color television. In 1928, while Alexander Fleming studied penicillin, Baird made the first successful transatlantic broadcast, beaming a signal from London to New York. Baird continued innovating, including the color television in 1944. Television was just one line of Baird’s creativity—he also developed many other less successful inventions, such as cozy thermal socks.

Modern Scottish Scientists

This list might seem long, but it’s only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Scotland and science. Countless other Scottish academics spent their lives in pursuit of knowledge, a tradition that continues today. Among them, perhaps most prominent is Robert Watson, whose work in climate science remains highly relevant today. The scientific legacy of Scotland is no doubt far from over.

Further Reading

“A Curious Herbal.” The British Library, The British Library, 30 Dec. 2014, www.bl.uk/collection-items/a-curious-herbal-dandelion.

Broadie, Alexander, editor. The Cambridge Companion to the Scottish Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Herman, Arthur. How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe’s Poorest Nation Created Our World & Everything in It. Crown, 2007.

“The Scientists.” Scottish Science Hall of Fame, National Library of Scotland, digital.nls.uk/scientists/biographies/index.html.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.