Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Scottish History & Life by James Paton, 1902

It is generally supposed that Scotland owns the game of Golf, which has for four or five centuries been identified with the nation as one of its favourite sports, to Holland. That a game akin to golf was played by the Dutch is sufficiently proved by the number of Dutch tiles and engravings extant which represent the players engaged at their game on the ice. Dr. Fowler, honorary secretary of the National Skating Association, some time ago discovered in a poem by the Dutch poet, Bredero, what is the earliest reference to golf hitherto brought to light. Mr. Martin Hardie, of the National Art Gallery, gives the following free translation of the passage:

The golfer binds his ice-spurs on,

Or something stiff to stand upon

For the smooth ice all snowless lying

Laughs and jests at polished soles.

Sides drawn by lot, the golfer stands

Ready to smite with ashen club

Weighted with lead, or his Scottish cleek

Of leaded box, three fingers broad, one thick,

The feather ball, invisible from drive to fall,

By forecaddies is keenly marked,

As he golf forward to a limit post,

Or strikes for the furthest, stroke against stroke,

At a white mark or a flag in the hole,

Notching the strokes on a slender branch,

Which each sticks deep in his jacket;

Who of his tally takes no heed,

Shall be out of it altogether.'

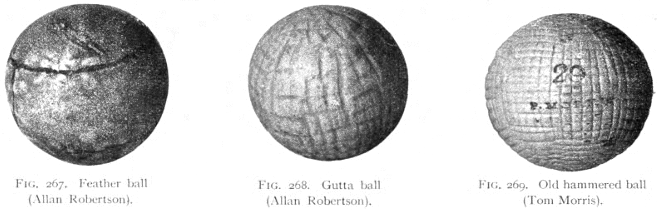

Three old golf balls. Images from text.

While this early reference shows that the game was known to the Dutch, it rather, by the mention of the Scottish cleek, favours the idea that its practice in Scotland was antecedent to that in Holland. While a 'flag in the hole' would imply that the Dutchmen did sometimes come so near our game as to make a hole for the ball to be putted out, most of the engravings simply indicate that a post or mark was put up on the ice, the winner evidently being the player who made the ball touch this in the fewest strokes. In a 'Book of Hours' (1500-1510) in the British Museum, Mr. Henry W. Maybecr, in 1894, unearthed a miniature illustration of players evidently putting at a hole, of which in the Illustrated London News of June 9th, 1894, he gives a full account as disproving Mr. Andrew Lang's contention that the early Flemish golfers never putted at holes. He even goes on to show that the players wore red coats, and that like some modern patents the clubs had steel faces. This is all very interesting, but still not conclusive. That a kind of golf was played in Holland need not be denied. It, however, was given up. On the other hand Scotland at quite as early a period was in the possession of this game, and to Scotland it owed at least its progress and development on its present lines.

The great popularity of the game of golf among the common people of Scotland some centuries ago, and the value set upon the practice of archery at that time, are well illustrated by some Acts of Parliament. In March, 1457, the Scots Legislature 'decreeted and ordained that wapinschawwingis be haldin be the Lordis and Baronis spirituale and temporale, four times in the zeir, and that the Fute-ball and golf be utterly cryit doune, and nocht usit; and that the bowe merkis be maid at ilk paroche Kirk a pair of buttis, and schuting be used ilka Sunday.' In May, 1471, a similar Act was passed, the object as expressed being for the opposing of 'Our auld enimies of England,' who were evidently then superior to the Scots as bowmen. Again in May, 1491, it was ordained 'That in na place of the realme there be usit Futc-ball, Golfe, or nther sik improfitabill sportis but for the common gude of the realme, and defence thairof, and that bowis and schutting be hautit, and bow-markes maid therefore ordained in ilk parochin, under the pain of fourtie shillinges, to be raised be the Schireffe and baillies foresaid.'

These Acts are the earliest reliable records of the existence of this game and its popularity in Scotland. They do not give us information as to its nature or the clubs and balls used, but it is probable that the game of those days was more allied to shinty than in the modern game.

'During the Time of the Sermonses,' an oil painting by J. C. Dullman, R.I., represents a common occurrence in the olden days when golfers were so keen on the game that they played during the time they should have been at Church, and came under arrest for what was then considered a crime. In 1592 and 1593 the Town Council of Edinburgh expressly forbade this Sunday golf, and John Henrie and Pat Rogie were prosecuted 'For playing off the Gowff on the Links of Leith every Sabbath the time of the sermonses.' In Kirk Session records numerous cases are quoted where delinquents had to sit several Sundays on the cutty-stool or suffer even worse punishment for this misdemeanour.

Perth, where Robert Robertson sat in the seat of repentance in 1604, must have been a sporting place in those days, for it is there that we come upon the earliest literary reference in this country to Golf and Curling, and curiously enough they are allied in their reference with Archery. In the Muses Threnodie written in 1620, and published in 1638, Henry Adamson, a 'stickit' minister of the Fair City, along with George Ruthven (1546-1638), a physician and surgeon in Perth, and a relative of the Earl of Gowrie, who suffered there in 1600 for alleged treason, mourn the death of a personal friend of both, and the trio were all addicted to Archery, Golf, and Curling.

About the time here referred to the game of Golf was in high repute with the Stuart Kings. They not only enjoyed the game themselves, but they encouraged it among the people, and as through Puritan influence the views of Sunday had been so narrowed that no recreations were allowed on that day, they did what they could to get their subjects to change their minds and their manners.

James VI. in 1618 declared his desire to be "That after the end of divine service, our good people be not disturbed, letted, or discouraged from any lawful recreation such as dauncing, either men or women, archerie for men leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation,' but prohibiting 'the said recreations to any that are not present in the Church at the Service of God before their going to the said recreations.'

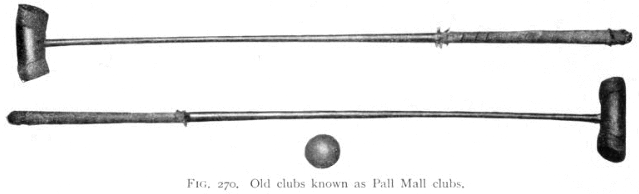

In 1603 the same King had appointed William Mayne to be royal clubmaker, and James Melville, ball maker. The clubs cost one shilling each, and the balls fourpence each, the latter being of leather stuffed with feathers (Fig. 267), His ill-fated son, Prince Henry, was a golfer, and from a Harleian MS. by one who saw him play the game, is described as 'not unlike to Pale-Maille.' It is evident that this was not golf, but as the Stuarts, and especially Charles II., were devotees of Pall Mall as well as of golf, the spectator referred to might readily have mixed them up. A set of the malls and balls used in Pall Mall is shown in Fig. 270.

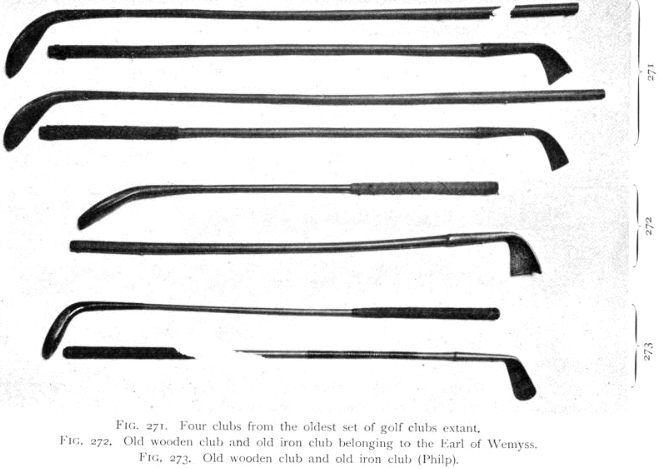

The oldest set of golf clubs extant (Fig. 271), were discovered in a boarded-up cupboard at 160 High Street, Hull, along with a paper bearing date 1741. The house, which has been rebuilt, was for the greater part of the eighteenth century the residence of a family of burgesses named Maisters. The clubs came into possession of Mr. Adam Wood, their present owner, through Mr. W. J. Hammond, who got them from Mr. Sykes, the present proprietor of the old mansion. Mr. A. J. Balfour, who has seen them, gives his opinion that they belong to the period of the Stuart Kings. There was every facility in the hundred and one specimens exhibited in Glasgow in 1901, for studying the development of the club from this most ancient set to comparatively modern times, the list closing with a complete set of Davie Strath's making. This brought the club-making up to 1878, since which year there has been considerable development in the way of bulging the face and shortening the head of the clubs. The lang-nebbit head is the peculiarity of the older form of club, and was singularly prominent in the case of the two clubs used by His Majesty the King, when as the Prince of Wales and a student in Edinburgh, he played golf at Musselburgh in 1859.

The cases owned by the Royal and Ancient Club, the Glasgow Club, the Royal Musselburgh Club, and the Edinburgh Burgess Club are all valuable as containing clubs and balls showing the various stages in the evolution of both. Perhaps the most notable complete set, after the Hull discovery, was that sent by Mr. J. E. Laidlay, a set of Philp's clubs, presented to him by the late Sir Hew Dalrymple, Bart., of North Berwick. Philp was the most finished club-maker of his day, and even yet his renown is as fresh as ever, for the exquisite finish of his workmanship has not been surpassed and an old ' Philp ' is a valuable relic wherever it is found. Young Tommy Morris' fame is commemorated by the championship belt (Fig. 274) which having been won by him three times in succession at Prestwick (then the only venue of the open championship) viz.., on Sept. 23, 1868 154 strokes; Sept. 10, 1869 157 strokes; Sept. 15, 1870 149 strokes; became his absolute property.

The trophy of Glasgow Golf Club, 1727-1828 a silver club and twenty-four balls attached, exhibited by Mr. Win. M'Inroy, is valuable as showing the make of the club and the appearance of the ball from year to year, for in this and other old clubs it was the custom for the captain each year to annex a ball of silver of the pattern of the period with his name and the date inscribed.

The balls on this trophy are all of the leather type, but the Honourable Company own three silver clubs and balls which run direct from 1744 to the present time, and on these the evolution of the ball could be fully traced. The leather was displaced by the gutta (Fig. 268) about 1846, one Paterson being the reputed inventor, though others disputed the claim. At first the gutta was almost smooth, but as it got hacked in play it flew better and this led to hand-hammering, which soon gave way to the cheaper process of casting in a mould.

The various changes may be noted in Figs. 267, 268, and 269. What further changes in clubs and balls may be in store it is not easy to predict, but the royal and ancient game is not likely to lose its place among Scottish sports.

Paton, James. Scottish History & Life. James MacLehose & Sons, 1902.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.