Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“The Stone Age,” from Scottish History and Life by James Paton, 1902.

The Stone Age...is the condition of a people using stone and other non-metallic materials, such as bone or horn, for their cutting tools and weapons; and it may be prehistoric or historic according to the people or the area of which it is the condition. As regards Western Europe, the Stone Age is prehistoric, and is subdivided into two periods called respectively the Palaeolithic, or old stone period, and the Neolithic, or new stone period.

To the palaeolithic period are assigned certain remains of man which are found chiefly in the old river gravels and in caverns. These remains consist for the most part of implements of flint of special forms which were manufactured by chipping alone, and are found associated with the remains of extinct animals of the quaternary geologic period, such as the mammoth, cave-bear, cave-lion, hyaena, musk-ox, rhinoceros, etc. The Stone Age of Scotland differs from that of England inasmuch as it has hitherto presented no unequivocal evidence of the presence of palaeolithic man. The story of the earliest known inhabitants of this country therefore begins in the period when its fauna consisted of animals still existing, though some may have since become locally extinct.

Perhaps the earliest inhabited sites yet discovered in Scotland are the caves at Oban, and the kitchen-middens or shell-mounds on the island of Oronsay. Four caves, opening in the cliff behind the old sea-beach on which the lower part of the town of Oban is built, have yielded evidence of occupation by man. The refuse of the food of the occupants consisted chiefly of the bones of the ox and swine, red deer and roe deer, various birds and fishes, and an extensive accumulation of the shells of the common edible molluscs and Crustacea of the adjacent shore.

Mingled with this mass of food-refuse were occasionally found implements of stone and bone of peculiar forms. No cutting implements of stone were found, except a knife-like flake of flint and a well-made flint scraper of the ordinary neolithic type. In one cave also were found a few fragments of coarse pottery. But the bone implements were very numerous, and among them the most characteristic were fish-spears, or small harpoons of bone or deer-horn with barbs along the sides (Figs. 1-4), and in one case (Fig. 1) with a perforation at the butt end for a line, so that it might be used as a harpoon with a disengaging head.

The harpoons of the palaeolithic period found in the caves of England and France with remains of the extinct animals have cylindrical shanks and free-standing barbs, whereas these have flat shanks, and the barbs are formed by cutting obliquely into the sides of the shank. Besides those from the Oban caves and from the Oronsay shell-heaps, the only other Scottish specimen known is that found in the river Dee in Kirkcudbrightshire (Fig. 5) belonging to the Kirkcudbright Museum.

The contents of the Oronsay kitchen-middens or refuse-heaps were of similar character—the similarity extending to the implements (which included bone harpoons) as well as to the refuse of the food, and thus indicating that the stage of culture was in both cases the same. But the facts that the people possessed domestic animals, subsisted by hunting and fishing, and had craft sufficient for navigation between the mainland and the isles, do not imply a stage of culture which can be called extremely low.

Judging from the human remains found in the Oban caves as well as from the other circumstances, Professor Sir William Turner says: 'From a certain community of character in all the four caves and their contents, more especially in the tools and implements found in them, one is led to the inference that the people who had occupied them belonged to the same epoch, and were of the same race. Although both the pottery and the implements were rude and simple in material and shape, yet from the absence of all remains of extinct animals their inhabitants cannot be referred to palaeolithic times, but are much later in date. It would seem appropriate to class them alongside of the men whose remains are associated with the dolmens in France and with the long barrows in England, for the adults agree in possessing dolicocephalic crania, a moderately low stature, and not unfrequently platycnemic tibiae.'

Dolmens, cromlechs, long barrows, giants’ graves, and many other names have been given at different times, and in different places, to the sepulchral constructions of the Stone Age. The megalithic erections, consisting of an enormous capstone supported on three or more vertical groups or pillar-stones, which are called cromlechs in Ireland and Wales are not found in Scotland. But the chambered cairns, analogous to the long barrows of England, the dolmens of France, and the gang-graben of Denmark, do form a conspicuous feature in the prehistoric aspect of Scotland.

Though the analogy among these sepulchral constructions is obvious, they cannot be said to be all similar. Each country has its own peculiarities and different groups even in the same country differ in certain features. But with all their variety of external form they furnish evidence from their contents of the prevalence of a certain community of burial customs and a certain similarity of attainment in culture.

The great chambered cairns of Scotland present several varieties in their external form as well as in their internal construction; but there are radically only two distinctive varieties—those having chambers with an entrance passage from the outside, and those having closed chambers, which are more of the nature of megalithic cists. In external form the cairn maybe long or short, round or oval, but the internal arrangement and the nature of the burial deposits must be regarded as the classifying features.

It is characteristic of the Scottish cairns that they appear to be distributed in local groups, each group having special features of its own. The northern group in Orkney, Caithness, and Sutherland has chamber and passage, but it also has the chamber definitely subdivided. The Clava group in the valley of the Nairn has chamber and passage, but it has sometimes an exterior encircling ring of standing stones like the great cairn at New Grange in Ireland. The Arran group has closed chambers or megalithic cists placed side by side. The Argyleshire group has examples of both varieties.

These cairns are not mere structureless heaps of stones piled over a chamber. When the external ruin is cleared away they are found to possess a definite ground-plan, outlined towards the exterior by a single or double wall, or sometimes by a setting of boulders or flat oblong stones placed end to end. Like the long barrows of England, the chambered cairns of Scotland are characterised by aggregate burial, cremated and uncremated, cremation however appearing to be the more prevalent custom, especially in the northern districts.

In the cairn of Unstan, near Stennis, Orkney (Fig. 6), which had a subdivided chamber 21 feet long by 6 ½ feet in breadth, entered by a passage 14 feet in length by 2 feet in width, there were found upon and in the floor a large quantity of bones, human and animal, mingled with ashes and charcoal, and the broken fragments of about thirty urns, of which only a few could be sufficiently reconstructed to show the shape. They were wide shallow, basin-shaped vessels of a hard black paste with rounded bottoms and nearly vertical brims ornamented with groups of parallel lines arranged in triangular spaces. Two of these urns are shown in Figs. 7 and 8. The implements found with them were a triangular arrow-head of flint with barbs and stem (Fig. 9) and two larger arrow-heads of finer workmanship of leaf-shaped form (Figs. 10 and 11), a flint knife with a ground edge, a scraper of flint, and one of those elongated tools known as fabricators (Fig. 12) because they seem to have been used in shaping other implements of flint by flaking.

A circular cairn at Camster in Caithness, 75 feet in diameter (Figs. 13 and 14) and about 18 feet high, had a central chamber subdivided into three compartments the first of which was roofed over by flat slabs while the others were both covered by one roof formed by the overlapping of the side walls until the width could be spanned by two flat slabs, The chamber was 10 feet in height and about 7 ½ feet in diameter, and was entered by a passage from the outside of the cairn of over 20 feet in length. The floor of the chamber was a compacted mass of ashes and burnt bones, human and animal, among which were chips of flint and many fragments of urns chiefly of a hard black paste and, in some cases, round bottomed. The only finished implement found was a well-made flint knife with a ground edge.

In the largest of the oblong cairns of Caithness (Fig. 15), which are from 240 to 190 feet in length, and present the peculiar prolongations at the ends that have suggested for them the appellation of horned cairns, the floors of the chambers were covered by layers of ashes, charcoal, and burnt and unburnt bones, human and animal, mingled with fragments of urns of a hard black paste. In the corner of one chamber was a cist set on the floor, which contained an urn of coarse reddish paste and twisted cord ornamentation, and a necklace of seventy beads of jet or lignite. In another of the horned cairns of smaller size at Ormiegill (Fig. 16) with a similar stratum of burnt burials in the floor, there were found a triangular hollow-based arrow-head of flint (Fig. 25), a flint knife with a ground edge, a number of saws and scrapers of flint, and a polished hammer of grey granite having a perforated haft-hole with perfectly straight sides.

In the chamber of another similar cairn at Garrywhin there were found among the ashes and bones, human and animal, which covered the floor, three leaf-shaped arrow-heads of flint. Of the Argyleshire cairns, one at Achnacree (Fig. 17), 75 feet in diameter and 15 feet high, had a subdivided chamber reached by a passage about 28 feet in length. In it was found a round-bottomed urn of the same hard black paste, and the fragments of another having ear-like projections from opposite sides like the handles of the modern quaich.

At Largie, near Kilmartin, a large dilapidated cairn of about 130 feet in diameter showed a chamber to which no passage was found. In the floor of the chamber and in the usual layer of ashes and burnt bones, human and animal, there were found several flake knives and scrapers, and five arrow-heads of flint, and also a round-bottomed urn of hard black paste ornamented with vertical scrapings all over the exterior surface.

In Arran a number of large cairns recently explored by Dr. T. H. Bryce contained subdivided chambers having no entrance passage from the outside, or megalithic cists placed side by side, along the central portion of the cairn. These subdivisions or cists contained the remains of several individuals who had been buried unburnt and apparently placed in the usual contracted position in the corners of the compartments. Their anatomical characters were found to be identical with those of the burials in the long barrows of England. The implements deposited with them were flint arrow-heads, scrapers, flake-knives, a polished stone axe, and a polished stone hammer not unlike that from the Caithness cairn, while the pottery consisted of vessels of hard black paste, round bottomed, and having ear-like projections on the upper part of the sides.

All these cairns, however much they may differ in details, are obviously of one constructional type distinguished by the presence of interior chambers, and by a definite external ground plan defined by a bounding wall or a setting of stones. The burial customs are the same in all aggregate burial, with or without cremation, and with deposit of grave-goods, of which only the imperishable parts, such as the stone heads of arrows and axe-hammers, have remained. The grave-goods probably included clothing, as we know that they included personal ornaments. Whether the clay vessels which accompany the other deposits were exclusively cinerary, or were used for other purposes, such as those connected with funeral feasts, we have no means of ascertaining.

Nor can we determine whether the remarkable accumulation of the bones of animals in the floors of the chambers may indicate a custom of including the domestic animals belonging to the dead among the grave-goods deposited with him, or whether, as suggested by the presence of the bones of wild animals, such as deer and wild birds, they may be the remains of funeral feasts consumed on each occasion of the reopening of the family tomb. But apart from this, the contents of these tombs show that the people were in possession of the domestic animals, that they also hunted the wild animals with success, that their tools and weapons, though made of flint and other stones, were well made, exhibiting taste as well as skill in their manufacture, and their pottery though not thrown on the wheel was not ungraceful in shape, and not destitute of character in the matter of its ornamentation.

With the help of the knowledge derived from the examination of the burial-places of the Stone Age we are enabled to select from the mixed multitude of objects that are casually found in the soil such tools, weapons, and ornaments as correspond with those of the burial deposits, and thus to classify them also as of Stone Age types. These are further classified by their forms and purposes, such as scrapers, knives, saws, borers, and fabricators, which are always made of chipped flint; axes and adzes which when made of flint are sometimes fashioned by chipping only, but more usually partly or wholly polished, and when made of other material than flint are always polished.

The weapons are arrow and spear-heads, which are always made of chipped flint, and war axes or hammers, seldom made of flint, but in general more or less finely polished. Excellent examples of the principal forms of all these different varieties of stone implements and weapons are in the collections exhibited by Mr. Tom Scott, A.R.S.A., Rev. John McEwen, Mr. William Forbes, Mr. William Smith, and the Falconer Museum, Forres.

The flint scrapers are the most abundant and ubiquitous tools of the Stone Age. They are of all sizes from little more than ½ an inch in diameter up to 2 ½ inches. The shape is constant, and resembles the broken off end of a round-nosed chisel which has the edge on one face of the blade (Figs. 18, 19). Many of them are so short that it is difficult to conceive how they could be effectively used for any purpose without being fixed in a handle of some kind. Some however are made from longer flakes so that the tool itself supplies the handle. The use of the scraper is conjecturally indicated by the name given to it, but probably it served for many purposes. A similar tool of stone inserted in a bone handle is used by the Esquimaux for scraping or currying skins. Besides the round-nosed scraper which is so common, there are side scrapers and hollow scrapers (Fig. 20), the latter having the scraping edge concave instead of convex. Its conjectural use was that of smoothing arrow-shafts to a regular roundness a purpose which it has been demonstrated to serve admirably.

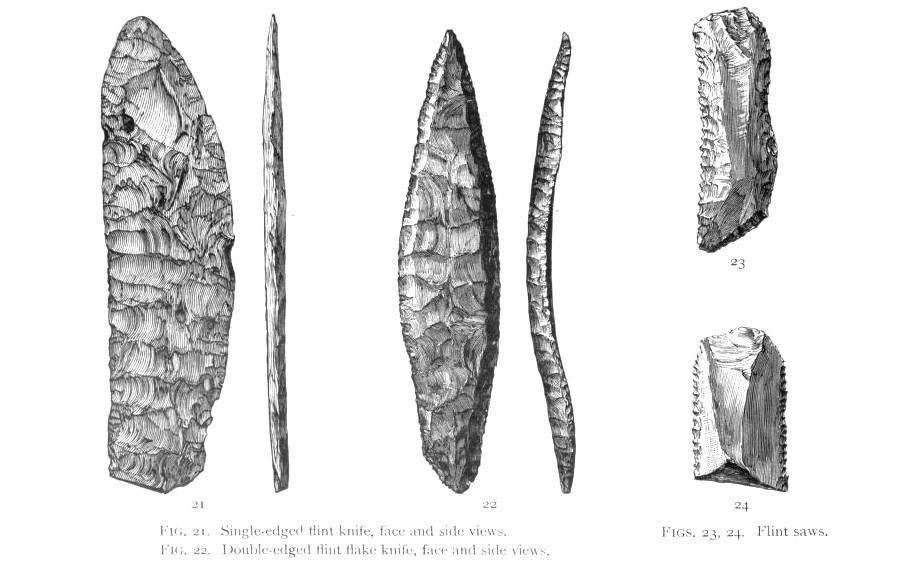

The flint knife is made from a long narrow flake by fine secondary chipping, so as to produce a cutting edge along its length on one side only, as in Fig. 21, or on both sides, as in Fig. 22. The cutting edge of a flint knife is thus always a rough edge, but may be very keen. Some flint knives have an edge made by grinding on both faces, but this method does not produce a keen edge, and these ground-edged knives may have been designed for some special purpose.

The flint saw (Figs. 23 and 24) is made from an elongated flake in the same way as the knife, but with the edge serrated. The teeth are often very fine and thickly set. From the thickness of the back of the flake the implement could not be used like a metal saw to cut completely through anything of much greater thickness than itself, but it could make a notch or furrow round a thick piece of bone or deer-horn so as to enable it to be broken across at the notched part. Such notched bones and pieces of deer-horn, partially sawn through and then broken across, are often met with on prehistoric sites.

The fabricator is a special tool of a stout punch-like shape, sometimes made from a flake ridged on the back and sometimes nearly cylindrical and carefully chipped all over the surface. It is usually from about 3 to 4 ½ inches in length, and has its ends much rounded and worn down by use, whether as a punch operated by a mallet, or by simple manual pressure, in the shaping and secondary working of such things as flint arrow and spear-heads and finely worked knives. A fabricator found with three arrow-heads in the cairn at Unstan is shown in Fig. 12.

Flint arrow-heads and lance or spear-heads differ only in size, and no sharp line can be drawn between them. There are two principal forms, the leaf-shaped (of which typical varieties are shown in Figs. 26, 28, and 29) and the triangular, though the transition form between them the double triangular, or lozenge-shape may also be considered a very numerous variety. But it is difficult to say where the line should be drawn between the transitional forms, which shade into each other almost imperceptibly.

Of the triangular form the commonest variety (shown in Figs. 30 to 34) is that with well-defined barbs and a stem or projecting tang in the middle of the base, which is not very common is that with a central notch or slot in the middle of the base by which it was fastened to the shaft-the shaft in this case being let into the arrow-head instead of the arrow-head being let into the shaft. Another rather rare variety is the single-barbed form (Fig. 25), which has a concave base and is lopsided. One side of the triangle in this case is always the thin natural unworked edge of the flake, and the other edge often shows ripple-flaking of a kind never seen on the other arrow-heads. From its peculiar form and features this variety has been regarded as intended for some other purpose than that of an arrow-head. The leaf-shaped arrow-heads are usually thinner and more finely made than those of the triangular form. They show a range of great variety of outline between the graceful slender-pointed leaf-shape and the almost geometrical lozenge-shape. The manner in which they were attached to the shaft was shown by an example (Fig. 27) found in a moss at Fyvie in Aberdeenshire.

The workmanship of these flint implements, which are usually finished by chipping only and were not polished (except in extremely rare instances chiefly found in Ireland), is always excellent, and often so delicate as not only to defy imitation but to baffle conjecture as to how it was done. Sir John Evans, who investigated the whole subject of flint-working, both practically and theoretically, and who had himself acquired no little skill in the art, confesses that the ancient method of producing the regular fluting, like ripple marks, by detaching parallel splinters uniform in size and extending almost across the surface of a lance or spear-head of flint, is a mystery. It is a lost art even to the savage tribes who have made their implements of stone to modern times, as well as a mystery to the man of science.

Flint axes are comparatively rare in Scotland, but, though few in number, they are often very finely finished. Some are manufactured by chipping only, others are ground on the cutting face only, as in Fig. 36, and others again of the finer varieties of chalcedonic flint are polished all over, and brought to a finish almost as careful as that of a modern lapidary polishing a gem. The axes made in other varieties of the harder stones are often highly polished, but few show the finish so well as those of flint. There is, however, a group of axes all of the same form, thin, triangular, and brought to a fine cutting edge, which are made of a greenish stone, almost resembling jadeite, and are always highly polished.

A typical example of this form is shown in Fig. 35, which was found in Berwickshire, and was exhibited in the collection of Mr. Tom Scott, A.R.S.A. Some of those made of porphyritic stone are no less remarkable for the fineness of their lines and the beauty of their finish. Stone axes present a great variety of form, scarcely two being found to be absolutely alike, but they may be divided into two principal varieties those that have both ends more or less alike in shape, as in Figs. 37 and 38 found in Forfarshire, and those that taper to a more or less pointed or conical form towards the butt end.

There is also an adze-shaped axe (Fig. 39) which, though it is similar at both ends, has the one face more or less flattened and the other rounded. Some stone axes, from having lain in circumstances that have altered the colour of the surface of the stone, show the marl; of the handle where it has protected the stone from the colouring or discolouring influences. One Scottish axe has been found in a peat moss with its handle of wood still in a sufficient state of preservation to show that the axe was passed through a hole in the handle. Other forms of handling were doubtless also in use.

Probably the finer axes of highly-polished flint and other stone were not intended for common purposes, but for ceremonial use, or as weapons of war or parade. This seems to apply even more generally to the smaller and finer class of axes or hammer axes which are perforated for the insertion of the handle. The very large and heavy wedge-shaped hammer axes (Figs. 40-42), with holes perforated through have been made for some special use, such as splitting specimens the perforation is usually accomplished by working from both sides till the two bores meet in the middle. This is not quite symmetrical, because it is difficult to make the two bores meet exactly, and the outer part of each half of the perforate a wider than the diameter of the bore at the centre. Some of the perforated hammers however, have the bore perfectly smooth and of the same width throughout (as in Figs 43, and 44).

It is commonly supposed that the boring of these hard stones was a very difficult process, but it is in reality simple enough though extremely tedious. Professor Rau of New York found that he could drill a round hole through a piece of diorite by rotating a spindle of ash or pine wood with sharp quartz sand as the abrading medium, but two hours' drilling only added about the thickness of an ordinary pencil line to the depth of the hole.

Many of these hammers and axe-hammers are very finely made, and some, in addition to their graceful shape, are elaborately ornamented. Two especially, from Corwen in Wales (Fig. 45) and Morayshire (Fig. 46), have the surface ground into a pattern of concave facets reminding one of the ornamentation of cut glass. It is interesting to remark that not only is the form of these two stone hammers the same, but the pattern of the ornamentation is the same, though the one was found in Wales and the other in the North of Scotland. It is still more interesting to notice that while the Welsh example has the pattern quite finished all over the surface, the Scottish example has only one end finished, and though the pattern is blocked out along the sides, it has not been further proceeded with.

In drawing conclusions as to the relative capacity indicated by the different methods employed in the manufacture of stone implements, it is sometimes argued that the art of making and finishing flint implements by chipping alone is a manifestation of a Lower capacity than the art of grinding or polishing. But the skill, dexterity, and experience required for the production of the finer forms of chipped flint implements are beyond all question of a far higher order than is required for the production of ground or polished implements. And it must not be forgotten that the prehistoric man in always finishing certain varieties of his flint implements by chipping, selected the process most suitable alike for the material and for the purpose in view; and it is to be regarded as an indication of his capacity that he did with his materials precisely what we do with ours investigated their qualities and capabilities and framed his instruments upon intelligent principles.

Paton, James. Scottish History and Life. Glasgow J. Maclehose, 1902.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.