Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Flame-bearers of Welsh History by Owen Rhoscomyl, 1905.

The Plot to Destroy Llwelyn

Now the Norman lords of Cymru — the lords-marcher as they were called — hated the Cymric Prince always, but neither did they love the King of England. They looked upon themselves as independent princes, each in his own domain.

So long as there were Princes of Cymru, however, to make war on the King of England, then the Kings of England would have to encourage the lords-marcher in their independence, that they might harass the Princes of Cymru. Once the Princes of Cymru were extinguished, then the next step of the Kings of England would be to crush the lords-marcher. Some of the Norman lords saw that, and they at least had no great wish to see Llywelyn crushed utterly.

Llywelyn knew this. Already some of the barons were in secret correspondence with him, and when he received word from Edmund Mortimer of Wigmore, one of the great lords-marcher, saying that he wished to come over to his side, he believed it. For the Mortimers were his cousins, descended from his father's sister, Gladys, daughter of Llywelyn the Great.

Now an English chronicler of that day tells us that Edmund Mortimer did this thing to please King Edward. Llywelyn had always believed that Edward would deal treacherously with him. Edward, therefore, to throw Llywelyn off his guard, chose Edmund Mortimer for this work, for Llywelyn had once spared the life of the father of this Mortimer, because of the kinship between them. He would never suspect treachery, then, from the Mortimers, who were his kinsmen and sons of the man whose life he had spared.

But there was another man in this dark plan who should stand forefront in the blame. That man was John Giffard, a baron whose lands lay close to those of the Mortimers, and who had just been appointed Constable of the new Castle of Builth.

Whether Edward set him to work with the Mortimers, or whether, as seems more probable, the Mortimers themselves took him into council and set him on the work, does not matter here. But, by the rewards which Edward gave him afterwards, it is certain that the actual plot which finally closed round Llwyelyn was his.

For he was even more the right man to deceive the intended victim than the Mortimers themselves. First and foremost, he was one of those barons who had joined Simon de Montfort in the struggle for English liberty. He was, indeed, one of the busiest under de Montfort — as long as he thought it would pay. In those old days, when the champions of English liberty looked to Llywelyn for the ready help he always gave, Giffard must have professed himself a great friend of the Prince.

Further, Giffard had married Maud Longsword (Longespee) who was also a cousin of Llywelyn, for whom she had a warm affection, as she proved afterwards. And that marriage, moreover, made him a lord-marcher, in right of his wife's possessions.

Lastly, Llywelyn, knowing him personally, would know him to be quite unscrupulous, as his whole record shows him to have been. He had deserted Montfort m the old days, when he thought that hero's star was waning, and he was always ready to steal lands and revenues, wherever he thought he could do it.

In fact, as the documents of his life show, John Giffard was always for himself, no matter who was king or prince. He had fought against Edward and his father, when he thought it would pay. He was capable of fighting against Edward again if he thought that would pay. He was therefore just the man to change sides once more, after the defeat of Luke de Tany had so altered all the prospects of the war. On all counts, then, he would be just the man to be the fittest tool in this affair.

The letters of Edmund Mortimer brought Llywelyn down to the valley of the Wye, with a little band of warriors from Gwynedd. John Giffard, Constable of Builth Castle, made him believe that Builth Castle would be given up to him. Never repeat that old phrase about 'The Traitors of Builth.'

The Men of Builth, fair play to them, were always as ready as the rest to come out for freedom. And the bard who composed the wild and fiery lament for Llywelyn speaks of Saxon, not Cymric, treachery. The only Saxon there was John Giffard.

Giffard had only just been appointed to the command of Builth. Before him, Roger L'Estrange, lord-marcher of Ellesmere and Knockyn, two Cymric lordships in what is now Shropshire, had been commanding there. The Cymry from Ellesmere and Knockin were still at Builth under Giffard when Llywelyn came down.

Now a year or two before this, when the castle was being built, Edward had commanded the father of the Mortimers to cut four roads in different directions from Builth. One of those roads was to a place which he called, in the document, by a name which it still bears, Cevn Bedd, or, as we now say, Cevn y Bedd. It was called Cevn Bedd because of the bedd or grave of some mighty chief of old, who lies buried at the foot of a stone on Waen Eli there.

The road from the Castle was cut accordingly. On the way it had to cross the River Yrvon, by a wooden bridge, of the sort still to be seen spanning the Upper Wye. From the bridge it continued along the ridge, following an ancient path, to the homestead of Cevn y Bedd, two miles from Builth. There one ancient trackway branched off to the right, north-west, to Lianavan Vawr, and beyond; while another, the one which the road had followed to this point, kept on forward for a little way, till it passed the head of a little dingle, with a clear spring in it, bubbling out in a tiny stream. There it turned to the left, south-west, to cross the Yrvon at another wooden bridge, within bow-shot of a ford which no man would think existed, unless someone pointed it out to him.

When Llywelyn came down he posted his little force on the high ground above the end of the road, between the two trackways. In front of him the road ran on to Builth, but the bridge that should carry it across the Yrvon had been destroyed, probably by Roger L'Estrange, after the defeat at Llandeilo had put all the lords-marcher on their defence. The lack of a bridge, however, would trouble Llywelyn little, and it was at this camp on the Cevn y Bedd, at the edge of Waen Eli, that the final phase of the plot against him was set in motion.

When the Eighteen Fell

Prince of romance from the first hour of his power, Llywelyn now entered on that scene which beggars all the sober inventions of romancers. Tradition — vivid, lasting, living tradition — still tells the tale of it, though in so wild a tangle that it needs much time and patience to straighten it out. But here is the story, partly from tradition and partly from ancient documents.

On Thursday, December 10, 1282, Llywelyn received a message from the plotters, luring him away to Aberedw, some miles down the Wye, below Builth, and on the other side of the stream. The snow was lying white on the world, and the rivers (deeper then than now) were running black and full, but the ford across the Wye at Llechryd was still passable.

Choosing eighteen of his household men, his bodyguard, Llywelyn rode to Llechryd, and crossed. There he left his eighteen to hold the ford till he should come back, and then, attended only by one squire, young Grono Vychan, son of his minister Ednyved Yychan, he pushed on down the valley to Aberedw.

At Aberedw he was to meet a young gentlewoman, who was to conduct him to a stealthy meeting with some chiefs of that district. If it be asked why he rode thus, almost alone and almost unarmoured, the answer is that he was on a secret errand, in which he must not attract attention to himself until he had seen the local chiefs, and arranged all the details of a rising on their part. The more secret and sudden that rising was, the more likely it was to succeed. He was taking one of the risks that a fearless captain takes in such a war. It was like him to do it, for he was a steadfast soul.

At Aberedw, however, the gentlewoman was not there to meet him. In truth, the whole message was part of the plot of Giffard and the Mortimers, though he did not know it yet.

Yet, as he waited, he thought of how the snow would betray which way he went, either in going to the secret meeting with the chiefs, or in stealing away for safety from any sudden enemies. Therefore he went to the smith of the place, Red Madoc of the Wide-mouth, and bade him take the thin shoes off the horses, and put them on again backwards. Anyone finding his tracks after that would think that he had been coming, not going.

Then, as dark fell, he found that the Mortimers, with their horsemen, were closing in round the place. Danger was upon him indeed. Swiftly he stole away with his squire, and hid himself in a cave which may still be seen at Aberedw.

All that night he lay hidden, and then, as soon as the earliest grey of dawn crept over the snowy earth, he stole away with his squire again, and rode back to Llechryd. He could only go slowly, so he had to go stealthily, for his horse could not gallop, because of its shoes being backwards.

At Llechryd he found his faithful eighteen, but by this time the river was too high for crossing there. They must find some bridge. Now, the nearest bridge was the one at Builth, under the walls of the great castle.

Llywelyn believed that, by the trick of the horse- shoes, he had thrown the Mortimers off his track. Also he remembered that Builth castle was to be delivered to him according to promise. He took his eighteen men and rode back to the bridge at Builth, no great distance down the valley.

He reached the bridge barely in time. The Mortimers at Aberedw had terrified Red Madoc, the smith, into confessing the trick of the horseshoes. Like hounds they were following his trail, and now they caught sight of him, crossing the bridge with his little troop.

The bridge was of wood like the rest of the bridges of that district. Llywelyn turned and broke it down behind him, the black flood of the full Wye mocking the Mortimers as they drew rein on their panting steeds, before the broken timbers. Their hoped-for victim had escaped for the moment. In their fury they turned and dashed back down the valley to cross at Y Rhyd (now called Erwood) eight miles below.

Llywelyn expected the castle of Builth to be given up to him. But the garrison refused, doubtless making some excuse of waiting till the country had risen. He could not waste time; the bridge on the road to Cevn y Bedd was gone; he took his eighteen and led the way along the southern bank of the Yrvon to another bridge, just above the little church of Llanynys. There he crossed, and posted the eighteen to hold that bridge, doubtless feeling himself safely returned from great peril.

In thankfulness for that escape, too, he caused a White friar to hold a service for him, perhaps at the end of the bridge, perhaps in the little church of Llanynys, beside the dark Yrvon. It does not matter much where the service was held, the whole of that ground was to be made sacred that day.

This done, Llywelyn went up to the grange of Llanvair, a farmstead belonging to the parish church of Builth, doubtless to get food and an hour's sleep, after the cold watching of that winter's night in the cave. After a frosty night of scout-work, one's eyes get very heavy when one gets warm next day, and a great drowsiness stills the blood, even of the stubbornest man.

Meanwhile the Mortimers had crossed the Wye at Erwood, and with Giffard were riding fast for the bridge of Orewyn, where the eighteen held their post. In headlong haste their leading squadron charged the bridge--but the eighteen had not been chosen in vain. They kept the bridge.

While the clamour was at its height, Grono Vychan roused Llywelyn and told him of it.

'Are not my men at the bridge?' demanded the prince.

'They are,' answered Grono.

'Then I care not if all England were on the other side,' returned Llywelyn proudly. He knew what manner of men he had left to hold that bridge.

But down in front of the bridge, where the enemy were shouting in their baffled rage, as they tried in vain to hew a way across, one of Giffard's captains spoke out. It was Helias ap Philip Walwyn, from lower down the Wye.

'We shall do no good here!' he shouted. 'But I know a ford, a little distance off, that they do not know of. Let some of the bravest and strongest come with me, and we can cross and take the bridge in rear.'

At once the bravest crowded after Helias to the ford, where the water seems as dark and deep in winter as the rest of the long black pool on either hand. They crossed.

The eighteen were charged in rear as well as in front. But they kept faith. Where Llywelyn had posted them, there they died. As men should end, proudly lighting, so they ended.

'Till the eighteen fell,' says the bard, 'it was well with Llywelyn ap Gruffydd.'

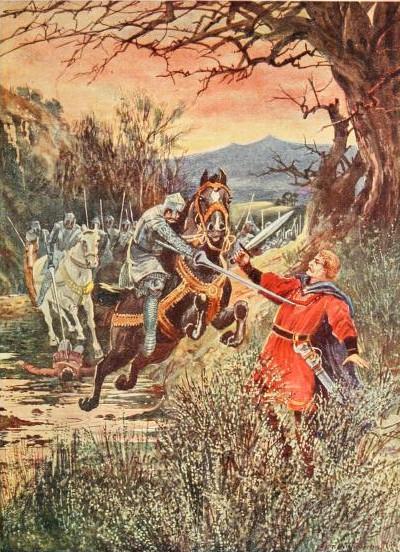

Then over their bodies poured all the mass of Mortimer's men, with Giffard's, to seek Llywelyn's little force on the high ground beyond. Fast the horsemen spurred, and as they hastened they came suddenly upon an unarmoured man with one companion, hurrying on foot towards where the bridge was roaring under the trampling host. One of the horsemen, Stephen or Adam of Frankton, in Llywelyn's old lordship of Ellesmere, dashed forward with his men, and one ran his lance through the younger of the two. The other one was running up through the little dingle, to get back to the army above in time to lead it in the coming battle. On the bank above the little spring at the head of the dingle, grew a great spread of broom (banadl). In that bush of broom Frankton overtook the man and ran his spear out through him in a mortal wound.

That man was Llywelyn. The accident had happened. Go to the spot, and the people will tell you that no broom has ever grown again in Llanganten parish from that dark day to this.

So died Llywelyn ap Gruftydd; a gallanter soul never passed to God.

Rhoscomyl, Owen. Flame-bearers of Welsh History. Welsh Educational Publishing, 1905.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.