Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“Earliest Recollections” from When I Was a Girl in Switzerland by Susanna Louise Patteson, 1921.

Some of my earliest recollections are not happy ones. I tell them in this chapter because I wanted my story to have a pleasant beginning.

The most “away back” incident that I can remember happened to a doll—a “bought” doll. My other dolls had all been rag dolls. And this was a boy-doll dressed in white knitted jacket, cap and trousers, like a Swiss lad in a winter sport suit. I do not remember who gave me that doll, but have always believed that I did not have it long, because the last time I saw it, it was still white and clean. That “last time” was when I looked through tears at my dollie as it floated a few minutes in a cistern before it sank from sight. Our neighbor boy Jacques had knocked it out of my hand.

Jacques was only a year older than I, but he was a big strong boy. He was a stutterer, and whenever he could not say the words he wanted to fast enough, he would make such terrible faces that any little girl would run for dear life. His orchard and ours joined where there was a ridge all the way across. In the cleft of that ridge every spring grew the pretty flowers which here we call snowdrops. I feel sure that some of those snowdrops grew on our side; but whenever I went to get any it seemed as though Jacques was lying in wait somewhere. He would wait until I was just on the point of picking a flower and then come on the run and make one of his frightful faces. It seemed as if he knew that that was all he had to do to scare any little girl.

It was the same way with a walnut-tree that stood in our orchard, but so close to the boundary line that nearly half the nuts fell over on Jacques’ side. It was my daily task to gather up the fruits that fell in our orchard, whether apples, pears, plums, or nuts. But just as sure as I stepped across the line for a nut Jacques would run out from hiding and pursue me.

One of my earliest recollections is the funeral of my uncle, Hans-Heiri. The last time I looked at him he lay in a casket outside the front door. All the young people of our village, led by the schoolmaster, sang around the casket. Then they formed a procession and went to the churchyard, four of the young men bearing the casket on their shoulders. Many were crying as they walked along. I was crying, too, but that was because I wasn’t allowed to be in the procession. I couldn’t see why those should cry who were in it. After they had all filed into the churchyard there was more singing at the grave, and then they went into the church. From a window I could see it all, and I was still crying when they came back home.

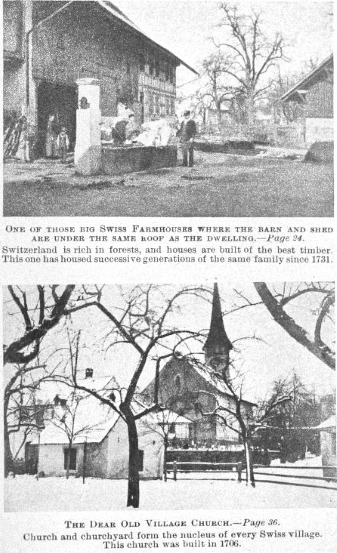

In Switzerland the Church is really a state institution, the same as the public school. During a visit some years ago to my old home I took pictures of the dear old village church just as a funeral procession was filing in through the churchyard gate. For the size of our village it was astonishing to me how many people turned out. It is a sort of unwritten law that at a funeral service every home in the village should be represented. Incidentally this photograph shows to the extreme left a part of my home and, in fact, the very window from which I watched Uncle Hans-Heiri’s funeral procession.

On the extreme right is shown a corner of the summer-house in the Pfarrhaus garden. The building in the background with that high, arched entrance was the fire-engine house. I recall only two fires in our village when the engine had to be called out. Each time my father sat in front with the driver. I shall never forget how the blazes flared up when the fire reached those wonderful feather beds, two enormous ones, with bolsters and huge pillows on every bedstead.

But to return to the picture: the one-story building in the foreground was our community wash-house. The Swiss of those days had more regard for utility than for appearance, and that squatty structure was made to face the main road right there in front of the churchyard and the Pfarrhaus, because the brook went by there, making it handy to get water. That brook then turned a right angle and passed between our house and the garden.

It was a wide and rapidly flowing brook, inclosed in stone masonry, the water clear as crystal, coming, no doubt, from the adjacent mountain, the “Höbrig.” A plank served as bridge between our house and garden, and immediately beyond the garden was our orchard. Farther on was the property of neighbor Jacques, and oh, the times I fell off that plank when pursued by him! Fortunately there were some steps in the masonry right there, leading down to the water’s edge, so I could always help myself out of the difficulty; and by the time I again reached dry land my pursuer was always out of sight.

My Uncle Hans-Heiri had been the drummer of the village band, and I remember how he used to toss and whirl those drumsticks. He was often called to play at the feasts and reunions which formed so prominent a part in the social and military life of the Swiss. Small as it is, Switzerland has a standing army of 250,000 able-bodied and trained soldiers; but they live in their homes, except during the few weeks a year which they spend at a garrison to be instructed in military tactics. They are great for holding shooting-matches, when all the young men who are under military training meet and have target practice.

Uncle Hans-Heiri never failed to bring me something nice on returning from his trips. I believe it was he who gave me that boy-doll. At the time of his death I was too young to realize my loss. Later, on listening to conversations between my father and his friends I learned what a fine young man he had been. In those days I used often to get up on a bench that lined the wall in the living-room and look at a wreath of flowers and leaves and buds that were made out of Uncle Hans-Heiri’s hair and mounted in a frame under glass. Then I used to cry because he was gone. From what I learned later, Uncle Hans-Heiri had been a soldier. I do remember that whenever he went away with his drum he was in uniform and wore a tall chapeau with chin-strap, and carried a knapsack.

When up on that bench, for want of better amusement, I used also to look at the baptismal certificates that hung on the wall. Mine had a special interest to me because on it was a picture of a handsomely dressed lady holding a baby in front of a baptismal font and Herr Pfarrer baptizing it. I always imagined I was the baby cuddled in those flowing white robes. As I grew older, I loved to read the verses under the picture. I must have read them many times, for to my great astonishment I can now recall the first of the four verses. Liberally translated, it is this:

An inexpressible blessing comes to you through baptism. It dedicates you as a child of God; therefore, be ever piously minded.

A short time after Uncle Hans-Heiri’s death, Grandfather died also. Then after another while my new mother came, and our Greta took a long vacation.

With that new regime in our home there came more happiness into my childhood. About that time I took a notion that I wanted my hair braided, as the older girls had it, and Mother consented. She also bought me a net with a ribbon ruche across the crown. But my friends all disliked the braids, and I soon went back to curls.

Up to that time I had always slept with Greta; but Mother brought among her dower a little walnut bedstead—for me. It was just long enough to stand at the foot of her bed without projecting at either side. I was very proud to have my own little bed for the first time in my memory, and that doll which I received on the wedding day had to sleep with me.

I remember how happy it made me when Mother stroked my cheeks in her affectionate way and smoothed my hair. I liked to be in the kitchen when she was cooking meals, and chat with her. I suspect that at such times I used to boast, as children will, of things I intended to do when I should be a grown-up. I remember hearing her tell little incidents of this kind. One that has lodged in my memory is her telling Aunt Verena that I had said that when I got big all she would have to do would be to help me.

I do not recall ever seeing Greta or any one else winding up our big stationary clock, but it is one of the first things I remember seeing Mother do. It became my ambition to be tall enough so that I could reach and pull down those stone weights, and set the hands.

About this time I began to do little chores around the house, such as bringing wood into the kitchen and carrying water from the village fountain. I had a tiny copper gelte about the size of a washbowl, and I always went with Mother to the fountain and carried some water home. The village housewives washed all such vegetables as lettuce, and spinach and chard at the fountain, each always using two geltes so as to change from one to the other. This sometimes made it rather crowded, and often the women got in each other’s way. I remember once seeing one shove her neighbor’s gelte full of spinach off the trough. The spinach lay there until evening when the cattle came to water and ate it. One of those women was Barbara, the seamstress, and the other her sister-in-law. After that they were no longer friends.

I still had another grandfather, but he lived a long way off; at least so it seemed to me, because we had to go there on foot and it was a two-hour journey. My father always took me there at least once a year, and at Grandfather’s some of my happiest young days were spent. That will make a chapter all by itself.

Patteson, Susanna Louise. When I Was a Girl in Switzerland. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.