“After having thus briefly noticed the gods, the giants, the dwarfs, etc., there remains for consideration a series of subordinate beings, who are confined to particular localities, having their habitation in the water, the forests and woods, the fields and in houses, and who in many ways come in contact with man.

A general expression for a female demon seems to have been Minne, the original signification of which was, no doubt, woman. The word is used to designate female water-sprites and wood- wives.

Holde is a general denomination for spirits, both male and female, but occurs oftenest in composition, as brunnenholden, wasserholden (spirits of the springs and waters). There are no bergholden or waldholden (mountain-holds, forest-holds), but dwarfs are called by the diminutive holdechen. The original meaning of the word is bonus genius, whence evil spirits are designated unholdes.

The name of Biliviz (also written Piltviz, Piletms, Buiweeks) is attended with some obscurity. The feminine form Bulwechsin also occurs. It denotes a good, gentle being, and may either, with Grimm, be rendered by aquum sciens, aequus, bontus; or with Leo by the Keltic bilbheitk, bilbhith (from bil, good, gentle, and bheith or bhith, a being). Either of these derivations would show that the name was originally an appellative; but the traditions connected with it are so obscure and varying, that they hardly distinguish any particular kind of sprite. The Bilwiz shoots like the elf, and has shaggy or matted hair.

In the latter ages, popular belief, losing the old nobler idea of this supernatural being, as in the case of Holla and Berchta, retained the remembrance only of the hostile side of its character. It appears, consequently, as a tormenting, terrifying, hair and beard-tangling, grain-cutting sprite, chiefly in a female form, as a wicked sorceress or witch. The tradition belongs more particularly to the east of Germany, Bavaria, Franconia, Voigtland and Silesia. In Voigtland the belief in the bilsen- or bilver-schnitters or reapers, is current. These are wicked men, who injure their neighbours in a most unrighteous way: they go at midnight stark naked, with a sickle tied on their foot, and repeating magical formulae, through the midst of a field of corn just ripe. From that part of the field which they have cut through with their sickle all the com will fly into their own barn. Or they go by night over the fields with little sickles tied to their great toes, and cut the straws, believing that by so doing they will gain for themselves half the produce of the field where they have cut.

The Schrat or Schratz remains to be mentioned. From Old High German glosses, which translate scratun by pilosi, and waltschrate by satyrus, it appears to have been a spirit of the woods.

In the popular traditions mention occurs of a being named Judel, which disturbs children and domestic animals. When children laugh in their sleep, open their eyes and turn, it is said the Judel is playing with them. If it gets entrance into a lying-in woman's room, it does injury to the new-bom child. To prevent this, a straw from the woman's bed must be placed at every door, then no Jiidel nor spirit can enter. If the Jiidel will not otherwise leave the children in quiet, something must be given it to play with. Let a new pipkin be bought, without any abatement of the price demanded; put into it some water from the child's bath, and set it on the stove. In a few days the Jiidel will have splashed out all the water. People also hang egg-shells, the yolks of which have been blown into the child's pap and the mother's pottage on the cradle by linen threads that the Jiidel may play with them instead of with the child. If the cows low in the night the Jiidel is playing with them. But what are the Winseln? We are informed that the dead must be turned with the head towards the east, else they will be terrified by the Winseln, who wander hither from the west.

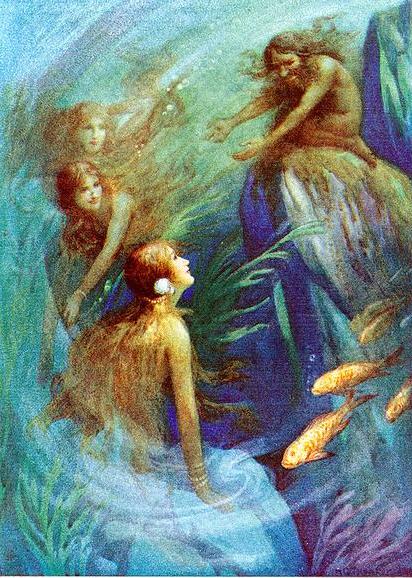

Of the several kinds of spirits which we classify according to the locality and the elements in which they have their abode the principal are the demons of the water or the Nixen. Their form is represented as resembling a human being, only somewhat smaller. According to some traditions the Nix has slit ears, and is also to be known by his feet, which he does not willingly let be seen. Other traditions give the Nix a human body terminating in a fish's tail, or a complete fishes form. They are clothed like human beings, but the water-wives may be known by the wet hem of their apron, or the wet border of their robe. Naked Nixen, or hung round with moss and sedge, are also mentioned.

Like the dwarfs, the water-sprites have a great love of dancing. Hence they are seen dancing on the waves, or coming on land and joining in the dance of human beings. They are also fond of music and singing. From the depths of a lake sweetly fascinating tones sometimes ascend, often times the Nixen may be heard singing. Extraordinary wisdom is also ascribed to them, which enables them to foretell the future. The water-wives are said to spin. By the rising, sinking, or drying up of the water of certain springs and ponds -caused, no doubt, by the Nix- the inhabitants of the neighbourhood judge whether the seasons will be fruitful or the contrary. Honours paid to the water-spirits in a time of drought are followed by rain, as any violation of their sacred domain brings forth storm and tempest. They also operate beneficially on the increase of cattle. They possess flocks and herds, which sometimes come on land and mingle with those of men and render them prolific.

Tradition also informs us that these beings exercise an influence over the lives and health of human beings. Hence the Nixen come to the aid of women in labour; while the common story as in the case of the dwarfs asserts the complete reverse. The presence of Nixen at weddings brings prosperity to the bride; and new-born children are said to come out of ponds and springs; although it is at the same time related that the Nixen steal children for which they substitute changelings. There are also traditions of renovating springs (Jungbrunnen), which have the virtue of restoring the old to youth.

The water-sprites are said to be both covetous and bloodthirsty. This character is, however, more applicable to the males than to the females, who are of a gentler nature, and even form connections with human beings, but which usually prove unfortunate. Male water-sprites carry off young girls and detain them in their habitations, and assail women with violence.

The water-sprite suffers no one from wantonness forcibly to enter his dwelling, to examine it, or to diminish its extent. Piles driven in for an aqueduct he will pull up and scatter; those who wish to measure the depth of a lake he will threaten; he frequently will not endure fishermen, and bold swimmers often pay for their temerity with their lives. If a service is rendered to the water- sprite, he will pay for it no more than he owes; though he sometimes pays munificently; and for the wares that he buys, he will bargain and haggle, or pay with old perforated coin. He treats even his relations with cruelty. Water-maidens who have stayed too late at a dance or other water-sprites, who have intruded on his domain, he will kill without mercy: a stream of blood that founts up from the water announces the deed. Many traditions relate that the water-sprite draws persons down with his net, and murders them; that the spirit of a river requires his yearly offering, etc.

To the worship of water-sprites the before-cited passage from Gregory of Tours bears ample witness. The prohibitions, too, of councils against the performance of any heathen rites at springs, and particularly against burning lights at them, have, no doubt, reference to the water-sprites. In later Christian times some traces have been preserved of offerings made to the demons of the water. Even to the present time it is a Hessian custom to go on the second day of Easter to a cave on the Meisner, and draw water from the spring that flows from it, when flowers are deposited as an offering. Near Louvain are three springs, to which the people ascribe healing virtues. In the North it was a usage to cast the remnants of food into waterfalls.

Rural sprites cannot have been so prominent in the German religion as water-sprites, as they otherwise would have acted a more conspicuous part in the traditions. The Osnabriick popular belief tells of a Tremsemutter, who goes among the corn and is feared by the children. In Brunswick she is called the Kornweib (Corn wife). When the children seek for cornflowers, they do not venture too far in the fields and tell one another about the Comwife who steals little children. In the Altmark and Mark of Brandenburg she is called the Roggenmohme and screaming children are silenced by saying: “Be still else the Roggenmohme with her long black teats will come and drag thee away.'' Or, according to other relations, “with her black iron teats.'' By others she is called Rockenmor, because like Holda and Berchta she plays all sorts of tricks with those idle girls who have not spun all off from their spinning-wheels (Rocken) by the twelfth day. Children that she has laid on her black bosom easily die. In the Mark they threaten children with the Erbsenmuhme, that they may not feast on the peas in the field. In the Netherlands the Long Woman is known who goes through the corn-fields and plucks the projecting ears. In the heathen times this rural or field sprite was, no doubt, a friendly being, to whose influence the growth and thriving of the com were ascribed.

Spirits inhabiting the forests are mentioned in the older authorities, and at the present day people know them under the appellations of Waldleute (Forest-folk), Holzleute (Wood-folk), Moosleute (Moss-folk), Wilde Leute (Wild folk). The traditions clearly distinguish the Forest-folk from the Dwarfs by ascribing to them a larger stature but have little more to relate concerning them than that they stand in a friendly relation to man frequently borrow bread and household utensils, for which they make requital; but are now so disgusted with the faithless world that they have retired from it. Such narratives are in close analogy with the dwarf-traditions, and it is, moreover, related of the females, that they are addicted to the ensnaring and stealing of children.

On the Saale they tell of Buschgrossmutter (Bush-grand-mother) and her Moosfratdein (Moss-damsels) . The Buschgrossmutter seems almost a divine being of heathenism, holding sway over the Forest-folk ; as offerings were made to her. The Forest-wives readily make their appearance when the people are baking bread, and beg to have a loaf baked for them also, as large as half a millstone, which is to be left at an appointed spot. They afterwards either compensate for the bread, or bring a loaf of their own batch, for the ploughmen, which they leave in the furrow or lay on the plough, and are exceedingly angry if any one slights it. Sometimes the Forest-wife will come with a broken wheelbarrow, and beg to have the wheel repaired. She will then, like Berchta, pay with the chips that fall, which turn to gold; or to knitters she gives a clew of thread that is never wound off. As often as any one twists the stem of a sapling, so that the bark is loosed, a Forest-wife must die. A peasant woman, who had given the breast to a screaming forest-child, the mother rewarded with the bark on which the child lay. The woman broke off a piece and threw it in her load of wood: at home she found it was gold.

Like the dwarfs the Forest-wives are dissatisfied with the present state of things. In addition to the causes already mentioned they have some particular reasons. The times, they say, are no longer good since folks count the dumplings in the pot and the loaves in the oven or since they piped the breads and put cumin into it. Hence their precepts:

“Peel no tree,

relate no dream,

pipe no bread, or

bake no cumin in bread,

so will God help thee in thy need…”

A Forest-wife, who had just tasted a new-baked loaf, ran off to the forest screaming aloud:

“They've baken for me cumin-bread,

that on this house brings great distress !”

And the prosperity of the peasant was soon on the wane, so that at length he was reduced to abject poverty.

Little Forest-men, who have long worked in a mill, have been scared away by the miller’s men leaving clothes and shoes for them. It would seem that by accepting clothes these beings were fearful of breaking the relation subsisting between them and men. We shall see presently that the domestic sprites act on quite a different principle.

We have still a class of subordinate beings to consider, viz. the domestic sprites or Goblins (Kobolde). Numerous as are the traditions concerning these beings, there seems great reason to conclude that the belief in them, in its present form, did not exist in the time of heathenism; but that other ideas must have given occasion to its development. The ancient mythologic system has in fact no place for domestic sprites and goblins. Nevertheless, we believe that by tracing up through popular tradition, we shall discern forms, which at a later period were comprised under the name of Kobolds.

The domestic sprites bear a manifest resemblance to the dwarfs. Their figure and clothing are represented as perfectly similar; they evince the same love of occupation, the same kind, though sometimes evil, nature. We have already seen that the dwarfs interest themselves in the prosperity of a family, and in this respect the Kobolds may be partially considered as dwarfs, who, for the sake of taking care of the family, fix their abode in the house. In the Netherlands the dwarfs are called Kaboutermannekens, that is, Kobolds.

The domestic sprite is satisfied with a small remuneration, as a hat, a red cloak, and party-coloured coat with tingling bells. Hat and cloak he has in common with the dwarfs.

It may probably have been a belief that the deceased members of a family tarried after death in the house as guardian and succouring spirits, and as such, a veneration might have been paid them like that of the Romans to their lares. It has been already shown that in the heathen times the departed were highly honoured and revered, and we shall presently exemplify the belief that the dead cleave to the earthly and feel solicitous for those they have left behind. Hence the domestic sprite may be compared to a lar familiaris, that participates in the fate of its family. It is, moreover, expressly declared in the traditions that domestic sprites are the souls of the dead, and the White Lady who, through her active aid, occupies the place of a female domestic sprite, is regarded as the ancestress of the family, in whose dwelling she appears.

When domestic sprites sometimes appear in the form of snakes, it is in connection with the belief in genii or spirits who preserve the life and health of certain individuals. This subject, from the lack of adequate sources, cannot be satisfactorily followed up ; though so much is certain, that as, according to the Roman idea, the genius has the form of a snake, so, according to the German belief, this creature was in general the symbol of the soul and of spirits. Hence it is that in the popular traditions much is related of snakes which resembles the traditions of domestic sprites. Under this head we bring the tradition, that in every house there are two snakes, a male and a female, whose life depends on that of the master or mistress of the family. They do not make their appearance until these die, and then die with them. Other traditions tell of snakes that live together with a child, whom they watch in the cradle, eat and drink with it. If the snake is killed, the child declines and dies shortly after. In general, snakes bring luck to the house in which they take up their abode, and milk is placed for them as for the domestic sprites…”

Sources:

"Northern Mythology: comprising the principle popular traditions and superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands" -Thorpe Benjamin, London, E. Lumley (1851)

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.