Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“The Sword Dance” from English Folk-Song and Dance by Frank Kidson and Mary Neal, 1915.

The Sword dance is still performed in the North of England, generally at Christmas time and on Plough Monday, 6th of January. It was originally part of a pageant or Mummers' play in which the ever-recurring drama of death and resurrection was acted in various forms.

Mr Sharp says that traces of it have been found in two southern English counties. Mr Carey found a dance called "Over the Sticks" in Sussex, but it has more of the characteristics of the Scotch sword dance, in which the swords are placed on the ground and the dancer shows his skill by dancing elaborate steps over and between the swords.

Sometimes in the Midlands a similar dance is found in which long Churchwarden pipes take the place of the sticks. The sword dances of Northern England are quite different, and are allied to those found in many European countries. These show traces of ancient ceremonial worship and the slaying of the sacrificial victim, and are more in the nature of drama than dance.

In Mysterium und Mimus im Rigveda, by Leopold von Schroeder (1908), there are some very interesting suggestions as to the meaning of these ceremonial sword dances, one of which, referring to the sword dance of Yorkshire called the Giants' dance, runs as follows (p. 118):—

''The leading feature of the dance, which was performed by masked peasants, was that two swords were swung around and on to the neck of a boy without hurting him. The circumstance is of great importance that the leading giant was called Woden and his wife Frigg. This shows us the mythological significance of the dance, clearly and without doubt. Whilst we here see Woden stepping forth as a great dancer, as the chief of a troop of giant dancers, we get a new and important feature in the representation of the god which makes him still more like the wild dancer Rudra-Shiva, a feature of which we hear nothing from other accounts of Wodan-Odin, and yet which is undoubtedly old and real. We must picture to ourselves here not the great heavenly god of the Edda, but rather the still far more primitive though already powerful spirit of the wind, of the soul, and of fruitfulness, from which the great god Woden has developed. Perhaps, too, we may see in the boy round whose neck the sword was swung harmlessly, the new-born, youthful spirit of fruitfulness: whom the swords shall symbolically protect, whose growth and thriving the sword dance, as a magical enchantment bearing fruitfulness, was in all probability intended to promote. In the same way the Curetes held the sword dance round the young Zeus, and the Corybantes round the infant Dionysos, in order to protect him. In my opinion it was also to promote his growth."

One is not so dependent on present-day dancers for a description of the sword dances as one is for that of the Morris dances, for certain records have survived. Olaus Magnus, in his History of the Northern Nations, thus describes the sword dance as practised by the Swedes and Goths: —

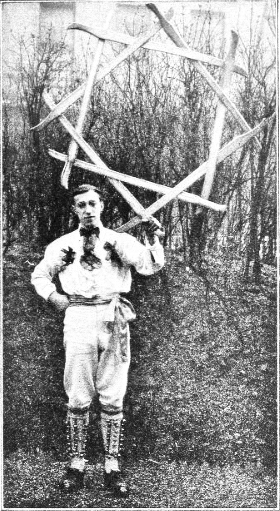

''First with their swords sheathed and erect in their hands they dance in a triple round. Then with their drawn swords held erect as before, afterwards extending them from hand to hand, they lay hold of each other's hilt and point while they are wheeling more moderately round, and changing their order, throw themselves into the figure of a hexagon which they call a rose. But presently, raising and drawing back their swords they undo that figure to form (with them) a four-square rose that may rebound over the head of each. At last they dance rapidly backwards, and vehemently rattling the sides of their swords together conclude the sport. Pipes or songs (sometimes both) direct the measure, which at first is slow, but increasing afterwards becomes a very quick one towards the conclusion."

He calls this a kind of Gymnastic Rite in which the ignorant were successively instructed by those who were skilled in it.

The first sword dance I saw performed was the Earsdon, which was accompanied by the small pipes. It looks very complicated, and is more interesting from an antiquarian point of view than from that of a dance. The performers keep huddled up together, and it is difficult for a spectator to see much of what is going on.

The second one I saw was at Flamborough, and it was danced by eight fishermen who have learnt it traditionally for longer than anyone living to-day can tell. This is a much more attractive dance, with more variety in the figures, and is almost identical with the description given by Olaus Magnus. Eventually I had two of the fishermen up to London, and they taught the dance to eight young men, who have in their turn passed it on to a great many others.

Mr Fuller Maitland has published the Sword Dance Song of Kirkby Malzeard in English County Songs, with the music. He considers that the tune of the Prologue has much of the Morris dance character, and that it was probably used for the actual dancing. The song describes each of the dancers, who comes out from among the rest as he is described by the singer. Old Thomas Wood of Kirkby Malzeard told Mr Bower, who took down the tune, that he would have nothing to do with the present Christmas sword dancers, or Moowers, "who have never had the full of it, and don't dress properly nor do it in any form, being a bad, idle company." They were originally taught by him, to make up his numbers at the Ripon Millenary Festival.

Mr Sharp has collected seven sword dances, including those of Earsdon, Flamborough, and Kirkby Malzeard, but probably none are danced as they were in the old days before more modern amusements took the place of the old folk festivals.

The sword dance, like the Morris, was essentially a man's dance, and whereas many of the Morris dances are quite suitable for women, the sword dance should be kept strictly as a man's dance.

Kidson, Frank and Neal, Mary. English Folk-Song and Dance. Cambridge University Press, 1915.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.