Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“I Organize the Battalion of Death” from Yashka, My Life as Peasant, Officer and Exile by Maria Bochkareva and Isaac Don Levine, 1919.

The journey to Petrograd was uneventful. The train was crowded to capacity with returning soldiers who engaged in arguments day and night. I was drawn into one such debate. Peace was the subject of all discussions, immediate peace.

"But how can you have peace with the Germans occupying parts of Russia?" I broke in. "We must win a victory first or our country will be lost."

"Ah, she is for the old regime. She wants the Tsar back," murmured threateningly some soldiers.

The delegate accompanying me here advised me to keep my mouth shut if I wanted to arrive safely in Petrograd. I heeded his advice. He left me at the station when we got to the capital. It was in the afternoon, and I had never been in Petrograd before. With the address of Rodzianko on my lips I went about making inquiries how to go there. I was finally directed to board a certain tram-car.

About five in the afternoon I found myself in front of a big house. For a moment I lost courage. "What if he has forgotten me? He may not be at home and nobody will know anything about me." I wanted to retreat, but where could I go? I knew no one in the city. Making bold, I rang the bell and awaited the opening of the door with a trembling heart. A servant came out and I gave my name, with the information that I had just arrived from the front to see Rodzianko. I was taken up in an elevator, a novelty to me, and was met by the secretary to the Duma President. He greeted me warmly, saying that he had expected me and invited me to make myself at home.

President Rodzianko then came out, exclaiming cheerfully:

“Heroitchik mine I I am glad you came," and he kissed me on the cheek. He then presented me to his wife as his heroitchik, pointing to my military decorations. She was very cordial and generous in her praise. “You have come just in time for dinner," she said, showing me into her bathroom to remove the dust of the journey. This warm reception heartened me greatly.

At the table the conversation turned to the state of affairs at the front. Asked to tell of the latest developments, I said, as nearly as I can remember:

"The agitation to leave the trenches and go home is growing. If there will be no immediate offensive, all is lost. The soldiers will leave. It is also urgent to return the troops now scattered in the rear to the fighting line."

Rodzianko answered approximately:

"Orders have been given to many units in the rear to go to the front. However, not all obeyed. There were demonstrations and protests on the part of several bodies, due to Bolshevist propaganda."

That was the first time I ever heard of the Bolsheviki. It was May, 1917.

"Who are they?" I asked.

"They are a group, led by one Lenine, who just returned from abroad by way of Germany, and Trotzki, Kolontai and other political emigrants. They attend the meetings of the Soviet at the Taurida Palace, in which the Duma meets, incite to strife among classes, and call for immediate peace."

I was further asked how Kerensky then stood with the soldiery, being informed that he had just left for a tour of the front.

“Kerensky is very popular. In fact, the most popular man with the front. The men will do anything for him," I replied.

Rodzianko then related an incident which made us all laugh. There was an old door-man in the Government Offices who had served many Ministers of the Tsar. Kerensky, it appeared, made it a habit to shake hands with everybody. So that whenever he entered his office he shook hands with the old door-man, quickly becoming the laughing-stock of the servants.

"Now, what kind of a Minister is it," the old foot-man was overheard complaining to a fellow-servant, “who shakes hands with me?"

After dinner Rodzianko took me to the Taurida Palace, where he introduced me to a gathering of soldiers’ delegates, then in session. I was given an ovation and a prominent seat. The speakers told of conditions at various sections of the front that tallied exactly with my own observations. Discipline was gone, fraternization was on the increase, the agitation to leave the trenches was gaining strength. Something had to be done quickly, they argued. How can the men be kept fit till the moment when an offensive is ordered? That was the problem.

Rodzianko arose and suggested that I be asked to offer a solution. He told them that I was a peasant who had volunteered early in the war and fought and suffered with the men. Therefore, he thought, I ought to know what was the right thing to do. Naturally, I was thrown into confusion. I was totally unprepared to make any suggestions and, therefore, begged to be excused for awhile till I thought the matter over.

The session continued, while I sank deep into thought. For half an hour I raked my brain in vain. Then suddenly an idea dawned upon me. It was the idea of a Women's Battalion of Death.

"You heard of what I have gone through and what I have done as a soldier," I turned to the audience upon getting the floor. "Now, how would it do to organize three hundred women like me to serve as an example to the army and lead the men into battle?"

Rodzianko approved of my idea. "Provided," he added, ''we could find hundreds more like Maria Botchkareva, which I greatly doubt."

To this objection I replied that numbers were immaterial, that what was important was to shame the men and that a few women at one place could serve as “an example to the entire front "It would be necessary that the women's organization should have no committees and be run on the regular army basis in order to enable it to serve as a restorative of discipline," I further explained.

Rodzianko thought my suggestion splendid and pictured the enthusiasm that would be bound to be provoked among the men in case of women occupying some trenches and taking the lead in an offensive.

There were objections, however, from the floor. One delegate got up and said:

"None of us will take exception to a soldier like Botchkareva. The men of the front know her and have heard of her deeds. But who will guarantee that the other women will be as decent as she and will not dishonor the army?"

Another delegate remarked:

"Who will guarantee that the presence of women soldiers at the front will not yield there little soldiers?"

There was a general uproar at this criticism. I replied:

''If I take up the organization of a women's battalion, I will hold myself responsible for every member of it. I would introduce rigid discipline and would allow no speech-making and no loitering in the streets. When Mother-Russia is drowning it is not a time to run an army by committees. I am a common peasant myself, and I know that only discipline can save the Russian Army. In the proposed battalion I would exercise absolute authority and get obedience. Otherwise, there would be no use in organizing it."

There were no objections to the conditions which I outlined as preliminary to the establishment of such a unit. Still, I never expected that the Government would consider the matter seriously and permit me to carry out the idea, although I was informed that it would be submitted to Kerensky upon his return from the front.

President Rodzianko took a deep interest in the project. He introduced me to Captain Dementiev, Commandant of the Home for Invalids, asking him to place a room or two at my disposal and generally take care of me. I went home with the Captain, who presented me to his wife, a dear and patriotic woman who soon became very much attached to me.

The following morning Rodzianko telephoned, suggesting that before the matter was broached to the War Minister, Kerensky, it would be wise to take it up with the Commander in Chief, General Brusilov, who could pass upon it from the point of view of the army. If he approved of it, it would be easier to obtain Kerensky's permission.

General Headquarters were then at Moghilev and there we went. Captain Dementiev ajid I, to obtain an audience with the Commander in Chief. We were received by his Adjutant on the 14th of May. He announced our arrival and purpose to General Brusllov, who had us shown in.

Hardly a week had elapsed since I left the front, and here I was again, this time not in the trenches, however, but in the presence of the Commander in Chief. It was such a sudden metamorphosis and I could not help wondering, deep in my soul, over the strange ways of fortune. Brusilov met us with a cordial hand-shaking. He was interested in the idea, he said. Wouldn't we sit down? We did. Wouldn't I tell him about myself and how I conceived the scheme?

I told him about my soldiering and my leaving the front because I could not reconcile myself to the prevailing conditions. I explained that the purpose of the plan would be to shame the men in the trenches by having the women go over the top first. The Commander in Chief then discussed the matter from various angles with Captain Dementiev and approved of my idea. He bade us adieu, expressing his hope for the success of my enterprise, and, in a happy frame of mind, I left for Petrograd.

Kerensky had returned from the front. We called up Rodzianko and told him of the result of our mission. He informed us that he had already asked for an audience with Kerensky and that the latter wanted to see him at seven o'clock the following morning, when he would broach the subject to him. After his call on Kerensky Rodzianko telephoned to tell us that he had arranged for an audience for me with Kerensky at the Winter Palace at noon the next day.

Captain Dementiev drove me to the Winter Palace and a few minutes before twelve I was in the ante-chamber of the War Minister. I was surprised to find Gen- eral Brusilov there and he asked me if I came to see Kerensky about the same matter. I replied in the af- firmative. He offered to support my idea with the War Minister, and introduced me right there to General Polovtzev, Commander of the Petrograd Military District, who was with him.

Suddenly the door swung open and a young face, with eyes inflamed from sleeplessness, beckoned to me to come in. It was Kerensky, at the moment the idol of the masses. One of his arms was in a sling. With the other he shook my hand. He walked about nervously and talked briefly and dryly. He told me that he had heard about me and was interested in my idea. I then outlined to him the purpose of the project, saying that there would be no committees, but regular discipline in the battalion of women.

Kerensky listened impatiently. He had evidently made up his mind on the subject. There was only one point of which he was not sure. Would I be able to maintain a high standard of morality in the organization? He would allow me to recruit it immediately if I made myself answerable for the conduct and reputation of the girls. I pledged myself to do so. And it was all done. I was granted the authority there and then to form a unit under the name of the First Russian Women's Battalion of Death.

It seemed unbelievable. A few days ago it had dawned upon me as a mere fancy. Now the dream was adopted as a practical policy by the highest in authority. I was transported. As Kerensky showed me out his eyes fell on General Polovtzev. He asked him to extend to me all necessary help. I was overwhelmed with happiness.

A brief consultation took place immediately between Captain Dementiev and General Polovtzev, who made the following suggestion:

"Why not start at the meeting to be held tomorrow night in the Mariynski Theater for the benefit of the Home for Invalids? Kerensky, Rodzianko, Tchkheidze, and others will speak there. Let us put Botchkareva between Rodzianko and Kerensky on the program."

I was seized with fright and objected strenuously that I could never appear publicly and that I would not know what to talk about.

"You will tell the same things that you told Rodzianko, Brusilov and Kerensky. Just tell how you feel about the front and the country," they said, brushing away my objections.

Before I had time to realize it I was already in a photographer's studio, and there had my picture taken. The following day this picture topped big posters pasted all over the city, announcing my appearance at the Mariynski Theater for the purpose of organizing a Women's Battalion of Death.

I did not close an eye during the entire night preceding the evening set for the meeting. It all seemed a weird dream. Where did I come in between two such great men as Rodzianko and Kerensky? How could I ever face an assembly of educated people, I, an illiterate peasant woman? And what could I say? My tongue had never been trained to smooth speech. My eyes had never beheld a place like the Mariynski Theater, formerly frequented by the Tsar and the Imperial Family. I tossed in bed in a state of fever.

"Holy Father," I prayed, my eyes streaming with tears, "show Thy humble servant the path to truth. I am afraid; instill courage into my heart. I can feel my knees give way; steady them with Thy strength. My mind is groping in the dark; illumine it with Thy light. My speech is but the common talk of an ignorant babai make it flow with Thy wisdom and penetrate the hearts of my hearers. Do all this, not for the sake of Thy humble Maria, but for the sake of Russia, my unhappy country.

My eyes were red with inflammation when I arose in the morning. I continued nervous all day. Captain Dementiev suggested that I commit my speech to memory. I rejected his suggestion with the comment:

"I have placed my trust in God and rely on Him to put the right words into my mouth.”

It was the evening of May the 21st, 1917. I was driven to the Mariynski Theater and escorted by Captain Dementiev and his wife into the former Imperial box. The house was packed, the receipts of the ticket office amounting to twenty thousand rubles. Everybody seemed to point at me, and it was with great difficulty that I controlled my nerves.

Kerensky appeared and was given a tremendous ovation. He spoke only about ten minutes. Next on the program was Mrs. Kerensky, and I was to follow her. Mrs. Kerensky, however, broke down as soon as she came out in the limelight. That did not add to my courage. I was led out as if in a trance.

"Men and women-citizens!” I heard my voice say. “Our mother is perishing. Our mother is Russia. I want to help save her. I want women whose hearts are crystal, whose souls are pure, whose impulses are lofty. With such women setting an example of self-sacrifice, you men will realize your duty in this grave hour!”

Then I stopped and could not proceed. Sobs choked the words in me, tremors shook me, my legs grew weak. I was caught under the arm and led away under a thunderous outburst of applause.

Registration of volunteers for the Battalion from among those present took place the same evening, there and then. So great was the enthusiasm that fifteen hundred women applied for enlistment. It was necessary to put quarters at my immediate disposal and it was decided to let me have the building and grounds of the Kolomensk Women's Institute, and I directed the women to come there on the morrow, when they would be examined and officially enlisted.

The newspapers carried accounts of the meeting and other publicity helped to swell the number of women who volunteered to join the Battalion of Death to two thousand. They were gathered in the garden of the Institute, all in a state of jubilation. I arrived with Staff Captain Kuzmin, assistant to General Polovtzev, Captain Dementiev and General Anosov, who was introduced to me as a man very interested in my idea. He looked about fifty and was of impressive appearance. He wanted to help me, he explained. In addition, there was about a score of newspaper men. I mounted a table in the center of the garden and addressed the women in the following manner:

"Women, do you know what I have called you here for? Do you realize clearly the task lying ahead of you? Do you know what war is? War I Look into your hearts, examine into your souls and see if you can stand the great test.

"At a time when our country is perishing it is the duty of all of us to rise to its succor. The morale of our men has fallen low, and it is up to us women to serve as an inspiration to them. But only those women who have entirely sacrificed their own personal interests and affairs could do it.

"Woman is naturally light-hearted. But if she can purge herself for sacrifice, then through a caressing word, a loving heart and an example of heroism she can save the motherland. We are physically weak, but if we be strong morally and spiritually we will accomplish more than a large force.

"I will have no committees in the Battalion. There will be strict discipline and guilt will be severely punished. There will be punishment for even slight disobediences. No flirtations will be allowed and any attempts at them will be punished by expulsion and sending home under arrest. It is the purpose of this Battalion to restore discipline in the army. It must, therefore, be irreproachable in character. Now, are you willing to enlist under such conditions?''

"Yes! We are! All right! All right!” the women responded in a chorus.

“I will now ask those of you who accept my terms to sign a pledge, binding you to obey any order of Botchkareva. I warn you that I am stem by nature, that I will personally punish any misdemeanor, that I will demand absolute obedience. Those of you who hesitate, better not sign the pledge. There will now be a medical examination."

There were nearly two thousand signed pledges. They included names of some of the most illustrious families in the country, as well as those of common peasant girls and domestic servants. The physical examination, given by ten physicians, some of whom were women, was not of the same standard as that required of the men. There were, naturally, very few perfect specimens of health among the women. But we rejected only those suffering from serious ailments. Altogether there were a few score rejections. Those accepted were allowed to go home with instructions to return on the day following when they would be quartered permanently in the Institute and begin training.

It was necessary to obtain outfits, and I applied to General Polovtzev, Commander of the Military District of Petrograd, for them. The same evening two thousand complete outfits were delivered at my headquarters. I also asked General Polovtzev for twenty-five men instructors, who were well disciplined, could maintain good order and knew all the tricks of the military game, so as to be able to complete the course of instruction in two weeks. He sent me twenty-five petty officers of all grades from the Volynski Regiment.

Then there was the question of supplies. Were we to have our own kitchen? It was found more expedient not to establish one of our own but to make use of the kitchen of a guard regiment, stationed not far from our quarters. The ration was that of regular troops, consisting of two pounds of bread, cabbage soup, kasha, sugar and tea. I would send a company at a time, equipped with pails, for their meals.

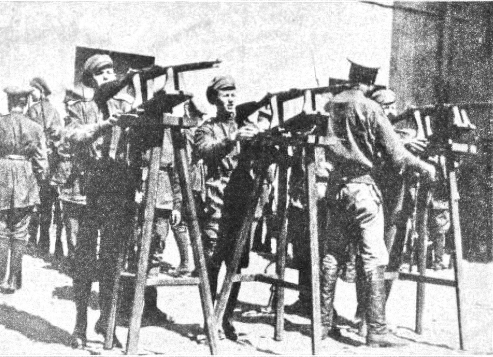

On the morning of May 26th all the recruits gathered at the grounds of the Institute. I had them placed in rows, so as to distribute them according to their height, and divided the whole body into two battalions of approximately one thousand each. Each battalion was divided into four companies, and each company sub-divided into four platoons. There was a man instructor in command of every platoon, and, in addition, there was a petty officer in command of every company, so that altogether I had to increase the number of men instructors to forty.

I addressed the girls again, informing them that from the moment they entered upon their duties they were no longer women, but soldiers. I told them that they would not be allowed to leave the grounds and that only between six and eight in the evening they would be permitted to receive relatives and friends. From among the more intelligent recruits—and there were many university graduates in the ranks—I selected a number for promotion to platoon and company officers, their function being limited at first to the internal management of the organization, since the men officers were purely instructors, returning to their barracks at the end of the day's training.

Next I marched the recruits to four barber shops, where from five in the morning to twelve at noon a number of barbers, using clippers, closely cropped one girl's head after another. Crowds outside the shops watched this unprecedented procedure, greeting with derision every hairless girl that emerged, perhaps with an aching heart, from the barber's parlors.

The same afternoon my soldiers received their first lessons in the large garden. A recruit was detailed to stand guard at the gate and not to admit anybody without the permission of the officer in charge. The watch was changed every two hours. A high fence surrounded the grounds, and the drilling went on without interference. Giggling was strictly forbidden, and I kept a sharp surveillance over the girls. I had about thirty of them unceremoniously dismissed the first day. Some were cast out for too much laughing, others for frivolities. Several of them threw themselves at my feet, begging mercy. However, I made up my mind that without severity I might just as well give it up at the beginning. If my word was to carry weight, it must be final and unalterable, I decided. How could one otherwise expect to manage two thousand women? As soon as one of them disobeyed an order I quickly removed her uniform and let her go. In this work it was quality and not quantity that counted, and I determined not to stop at the dismissal of even several hundred of the recruits.

We received five hundred rifles for training purposes, sufficient only for a quarter of the force. This necessitated the elaboration of a method whereby the supply of rifles could be made use of by the entire body. It was thought wiser to have the members of the Battalion of Death distinguished by special insignia. We, therefore, devised new epaulets, white, with a red and black stripe. A red and black arrowhead was to be attached to the right arm. I had two thousand of such insignia ordered.

When evening came and the hour for going to bed struck, the girls ignored the order to turn in for the night at ten o'clock and continued to fuss about and make merry. I called the officer in charge to account, threatening to place her at attention for six hours in the event of the soldiers keeping awake after ten. Fifty of the girls I had right there punished by ordering them at attention for two hours. To the rest I exclaimed:

"Every one of you to bed this instant! I want you to be so quiet that I could hear a fly buzz. To-morrow you will be up at five o'clock."

I spent a sleepless night. There were many things to think about and many worries to overcome.

At five only the officer in charge was up. Not a soul stirred in the barracks. The officer reported to me that she had called a couple of times on the girls to arise, but none of them moved. I came out and in a thundering voice ordered :

“Vstavai!“

Frightened and sleepy, my recruits left their beds. As soon as they got through dressing and washing there was a call to prayer. I made praying a daily duty. Breakfast followed, consisting of tea and bread.

At eight I had issued an order that the companies should all, in fifteen minutes, be formed into ranks, ready for review. I came out, passed each company, greeting it. The company would answer in a chorus:

“Zdravia zhelaiem, gospodin Natchalnik!”

Training was resumed, and I continued the combingout process. As soon as I observed a girl coquetting with an instructor, carrying herself lightly, playing tricks and generally taking it easy, I quickly ordered her out of the uniform and back home. In this manner I weeded out about fifty on the second day. I could not emphasize too much the burden of responsibility I carried. I constantly appealed for the most serious attitude possible on the part of the soldiers toward our task. The Battalion had to be a success or I would become the laughing-stock of the country, disgracing at the same time the sponsors of my idea, who grew in numbers daily. I took no new applicants, because haste in completing the course of training to rush the Battalion to the front was of the greatest importance.

For several days the drilling went on, the girls acquiring the rudiments of soldiering. On several occasions I resorted to slapping as punishment for misbehavior.

One day the sentry reported to the officer in charge that two women, one a famous Englishwoman, came to see me. I ordered the Battalion at attention while I received the two callers, who were Emmeline Pankhurst and Princess Kikuatova, the latter of Avlium I knew.

Mrs. Pankhurst was introduced to me and I had the Battalion salute “the eminent visitor who had done much for women and her country." Mrs. Pankhurst became a frequenter of the Battalion, watching it with absorbing interest as it grew into a well disciplined military unit. We became very much attached to each other. Mrs. Pankhurst invited me to a dinner at the Astoria, Petrograd's leading hotel, at which Kerensky was to be present and the various Allied representatives in the capital.

Meanwhile, the Battalion was making rapid progress. At first we were little annoyed. The Bolshevik agitators did not think much of the Idea, expecting It to collapse quickly. I received only about thirty threatening letters in the beginning. It gradually, however, became known that I maintained the strictest discipline, conunanding without a committee, and the propagandists recognized a menace In me, and sought a means for the destruction of my scheme.

On the evening appointed for the dinner I went to the Astoria. There Kerensky was very cordial to me. He told me that the Bolsheviki were preparing a demonstration against the Provisional Government and that at first the Petrograd garrison had consented to organize a demonstration in favor of the Government. However, later the garrison wavered in its decision. The War Minister then asked me if I would march with the Battalion for the Provisional Government.

I gladly accepted the invitation. Kerensky told me that the Women's Battalion had already exerted beneficial influence, that several bodies of troops had expressed a willingness to leave for the front, that many invalids of the war had organized for the purpose of going to the fighting line, declaring that if women could fight then they—the cripples—would do so, too. Finally he expressed his belief that the announcement of the marching of the Battalion of Death would stimulate the garrison to follow suit.

It was a pleasant evening that I spent at the Astoria. Upon leaving, an acquaintance who went In the same direction offered to drive me to the Institute. I accepted the Invitation, getting off, however, within a block of headquarters, as I did not wish him to drive out of his way. It was about eleven o'clock when I approached our temporary barrack. There was a small crowd at the gate, about thirty-five men, of all descriptions, soldiers, hooligans, vagrants, and even some decent-looking fellows.

"Who are you? What are you doing here?” I questioned sharply.

"Natchalnik,” cried out the sentry, "they are waiting for you. They have been here more than an hour, breaking the gate and scouring the grounds and building for you. When they became convinced that you were away they decided to wait here for your return."

"Now, what do you want?” I demanded of the group as they surrounded me.

"What do we want, eh? We want you to disband the Battalion. We have had enough of this discipline. Enough blood has been shed. We don't want any more armies and militarism. You are only creating new troubles for the common people. Disband your Battalion and we will leave you alone."

"I will not disband!" was my answer.

Several of them pulled out revolvers and threatened to kill me. The sentry raised an alarm and all the girls appeared at the windows, many of them with their rifles ready.

"Listen," a couple of them argued again, "you are of the people and we only want the weal of the common man. We want peace, not war. And you are inciting to war again. We have had enough war, too much war. We only now understand the futility of war. Surely you don't like to see the poor people slaughtered for the sake of the few rich. Come, join our side, and let's all work for peace."

"Scoundrels!" I shouted with all my strength. "You are idiots! I am myself for peace, but we will never have peace without driving the Germans out of Russia. They will make slaves of us and ruin our country and our freedom. You are traitors!"

Suddenly I was kicked violently in the back. Some one dealt me a second blow from the side.

"Fire!" I shouted to my girls at the windows as I was knocked down, knowing that I had instructed them always to shoot in the air first as a warning.

Several hundred rifles rang out in a volley. My assailants quickly dispersed, and I was safe. However, they returned during the night and stoned the windows, breaking every pane of glass fronting the street.

Bochkareva, Maria and Levine, Isaac Don. Yashka, My Life as Peasant, Officer and Exile. Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1919.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.