Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Livy, Vol III. by Livy, translated by George Baker, 1833.

5. But, from the day on which he was declared chief, he acted as if Italy had been decreed to him as his province, and he had been commissioned to wage war with Rome. Thinking every kind of delay imprudent, lest, while he procrastinated, some unforeseen event might disconcert his design, as had been the case of his father Hamilcar, and afterwards of Hasdrubal, he determined to make war on the Saguntines: and, as an attack on them would certainly call forth the Roman arms, he first led his army into the territory of the Olcadians, a nation beyond the Iberus; which, though within the boundaries of the Carthaginians, was not under their dominion, in order that he might not seem to have aimed directly at the Saguntines, but to be drawn on into a war with them by a series of events, and by advancing progressively, after the conquest of the adjoining nations, from one place to the next contiguous. Here he took and plundered Althea, the capital of the nation, abounding in wealth; and this struck such terror into the smaller cities that they submitted to his authority, and to the imposition of a tribute.

He then led his army, flushed with a victory and enriched with spoil, into winter-quarters at New Carthage. Here, by a liberal distribution of the booty, and by discharging punctually the arrears of pay, he firmly secured the attachment both of his own countrymen and of the allies; and, at the opening of the spring, carried forward his arms against the Vaccaeans, from whom he took by storm the cities Hermandica and Arbacala. Arbacala, by the bravery and number of its inhabitants, was enabled to make a long defence. Those who escaped from Hermandica, joining the exiles of the Olcadians, the nation subdued in the preceding summer, roused up the Carpetans to arms, and attacking Hannibal as he was returning from the country of the Vaccaeans, not far from the river Tagus, caused a good deal of disorder among his troops, incumbered as they were with spoil. Hannibal avoided fighting, and encamped on the bank; then, as soon as the enemy afforded him an opportunity, he crossed the river by a ford, and carried his rampart to such a distance from its edge as to leave room for the enemy to pass over, resolving to attack them in their passage.

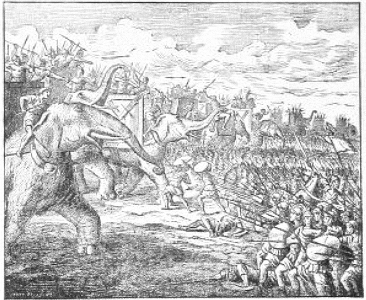

He gave orders to his cavalry, that as soon as they should see the troops advance into the water they should fall on them: his infantry he formed on the bank, with forty elephants in their front. The Carpetans, with the addition of the Olcadians and Vaccasans, were one hundred thousand in number; an army not to be overcome, if a fight were to take place in an open plain. These being naturally of an impetuous temper, and confiding in their numbers, believing also that the enemy’s retreat was owing to fear, and thinking that there was no obstruction to their gaining an immediate victory but the river lying in their way, they raised the shout, and without orders rushed from all parts into it, every one by the shortest way.

At the same time a vast body of cavalry pushed from the opposite bank into the river, and the conflict began in the middle of the channel, where they fought on very unequal terms: for in such a situation the infantry, not being secure of footing, and scarcely able to bear up against the stream, were liable to be borne down by any shock from the horse, though the rider were unarmed, and took no trouble; whereas a horseman, having his limbs at liberty, and his horse moving steadily, even through the midst of the eddies, could act either in close fight or at a distance. Great numbers were swallowed up in the current; while several, whom the eddies of the river carried to the Carthaginians’ side, were trodden to death by the elephants.

The hindmost, who could more safely retreat to their own bank, attempting to collect themselves into one body from the various parts to which their terror and confusion had dispersed them, Hannibal, not to give them time to recover from their consternation, marched into the river with his infantry in close order, and obliged them to fly from the bank. Then, by ravaging their country, he reduced the Carpetans also, in a few days, to submission. And now all parts of the country beyond the Iberus, except the territory of Saguntum, was under subjection to the Carthaginians.

6. As yet there was no war with the Saguntines; but disputes, which seemed likely to be productive of war, were industriously fomented between them and their neighbors, particularly the Turdetans: and the cause of these latter being espoused by the same persons who first sowed the seeds of the contention, and plain proofs appearing that not an amicable discussion of rights, but open force, was the means intended to be used, the Saguntines despatched ambassadors to Rome to implore assistance in the war, which evidently threatened them with immediate danger.

The consuls at Rome, at that time, were Publius Cornelius Scipio and Tiberius Sempronius Longus; who, after having introduced the ambassadors to the senate, proposed that the state of the public affairs should be taken into consideration. It was resolved that ambassadors should be sent into Spain, to inspect the affairs of the allies; instructed, if they saw sufficient reason, to warn Hannibal not to molest the Saguntines, the confederates of the Roman people; and also to pass over into Africa, to represent at Carthage the complaints of these to the Romans.

After this embassy had been decreed, and before it was despatched, news arrived, which no one had expected so soon, that Saguntum was besieged. The business was then laid intire before the senate, as if no resolution had yet passed. Some were of opinion that the affair should be prosecuted with vigorous exertions, both by sea and land, and proposed that Spain and Africa should be decreed as the provinces of the consuls: others wished to direct the whole force of their arms against Spain and Hannibal; while many thought that it would be imprudent to engage hastily in a matter of so great importance, and that they ought to wait for the return of the ambassadors from Spain.

This opinion being deemed the safest, was adopted; and the ambassadors, Publius Valerius Flaccus and Quintus Baebius Tamphilus, were on that account despatched, with the greater speed, to Saguntum, to Hannibal; and, in case of his refusing to desist from hostilities, from thence to Carthage, to insist on that general being delivered up to atone for the infraction of the treaty.

7. While the Romans were employed in these deliberations and preparatory measures, the siege of Saguntum was prosecuted with the utmost vigor. This city, by far the most wealthy of any beyond the Iberus, stood at the distance of about a mile from the sea: the inhabitants are said to have come originally from the island Zacynthus, and to have been joined by some of the Rutulian race from Ardea. They had grown up, in a very short time, to this high degree of opulence, by means of a profitable commerce, both by sea and land, aided by the increase of their numbers, and their religious observance of compacts, which they carried so far as to maintain the faith of all engagements inviolate, even should they tend to their own destruction.

Hannibal marched into their territory in a hostile manner, and, after laying all the country waste, attacked their city on three different sides. There was an angle of the wall, which stretched down into a vale, more level and open than the rest of the ground round the place: against this he resolved to carry on his approaches, by means of which the battering-ram might be advanced up to the walls. But although the ground at some distance was commodious enough for the management of his machines, yet, when the works came to be applied to the purpose intended, it was found to be no way favorable to the design; for it was overlooked by a very large tower; and, as in that part longer was apprehended, the wall had been raised to a might beyond that of the rest. Besides, as the greatest share of fatigue and danger was expected there, it was defended with the greater vigor by a band of chosen young men.

These, at first with missile weapons, kept the enemy at a distance, nor suffered them to carry on any of their works in safety. In a little time they not only annoyed them from the tower and he walls, but had the courage to sally out on the works and posts of the enemy; in which tumultuary engagements the Saguntines generally suffered not a greater loss of men than the Carthaginians. But Hannibal himself happening, as he approached the wall with too little caution, to be wounded severely in the forepart of the thigh with a heavy javelin, and falling in consequence of it, such consternation and dismay spread through all the troops around him that they were very near deserting their posts.

8. For some days following, while the general’s wound was under cure, there was rather a blockade than a siege. But although during this time there was a cessation of arms, there was no intermission of the preparations, either for attack or defence. Hostilities therefore commenced anew with a greater degree of fury; and the machines began to be advanced, and the battering-rams to be brought up, in a greater number of places; so that in some parts there was scarcely room for the works.

The Carthaginian had great abundance of men; for it is credibly asserted that the number of his troops was not less than one hundred and fifty thousand: the townsmen were obliged to have recourse to various shifts, in order, with their small numbers, to execute every necessary measure, and to make defence in so many different places; nor were they equal to the task: for now the walls began to be battered with the rams; many parts of them were shattered; in one place a large breach left the city quite exposed: three towers, in one range, together with the whole extent of wall between them, tumbled down with a prodigious crash; and so great was the breach, that the Carthaginians looked on the town as already taken.

On which, as if the wall had served equally for a covering to both parties, the two armies rushed to battle. Here was nothing like the disorderly kind of fight which usually happens in the assault of towns, each party acting as opportunity offers advantage, but regular lines were formed, as if in the open plain, on the ground between the ruins of the walls and the buildings of the city, which stood at no great distance.

Their courage was animated to the greatest height; on one side by hope, on the other by despair; the Carthaginian believing that only a few more efforts were necessary to render him master of the place; the Saguntines forming with their bodies a bulwark to their native city, instead of its wall, of which it had been stripped; not one of them giving ground, lest he should make room for the enemy to enter by the space. The greater therefore the eagerness of the combatants, and the closer their ranks, the more wounds consequently were received, no weapon falling without taking effect either in their bodies or armor.

9. The Saguntines had a missile weapon called falarica, with a shaft of fir, round, except towards the end, to which the iron was fastened: this part, which was square, as in a javelin, they bound about with tow and daubed with pitch: it had an iron head three feet long, so that it could pierce both armor and body together: but what rendered it most formidable was, that being discharged with the middle part on fire, and the motion itself increasing greatly the violence of the flame, though it struck in the shield without penetrating to the body, it compelled the soldier to throw away his arms, and left him without defence against succeeding blows. Thus the contest long continued doubtful; and the Saguntines, finding that they succeeded in their defence beyond expectation, assumed new courage; while the Carthaginian, because he bad not obtained the victory, deemed himself vanquished.

On this the townsmen suddenly raised a shout, pushed back the enemy among the ruins of the wall, drove them off from that ground, where they were embarrassed and confused, and, in fine, compelled them to fly in disorder to their camp.

10. In the mean time an account was received that ambassadors had arrived from Rome; on which Hannibal sent messengers to the sea-shore to meet them, and to acquaint them that it would not be safe for them to come to him through the armed bands of so many savage nations; and besides, that in the present critical state of affairs, he had not leisure to listen to embassies. He saw clearly, that on being refused audience, they would proceed immediately to Carthage: he therefore despatched messengers and letters beforehand to the leaders of the Barcine faction, charging them to prepare their friends to act with spirit, so that the other party should not be able to carry any point in favor of the Romans. Thus the embassy there proved equally vain and fruitless, excepting that the ambassadors were received and admitted to audience.

Hanno alone, in opposition to the sentiments of the senate, argued for their complying with the terms of the treaty, and was heard with great attention, rather out of the respect paid to the dignity of his character, than from the approbation of the hearers. He said that “he had formerly charged and forewarned them, as they regarded the gods, who were guarantees and witnesses of the treaties, not to send the son of Hamilcar to the army.

“That man’s shade” said he, “cannot be quiet, nor any one descended from him; nor will treaties with Rome subsist as long as one person of the Barcine blood and name exists. As if with intent to supply fuel to fire, you sent to your armies a young man, burning with ambition for absolute power, to which he could see but one road, the exciting of wars, one after another, in order that he might live surrounded with arms and legions. You yourselves therefore have kindled this fire with which you are now scorched: your armies now invest Saguntum, a place which they are bound by treaty not to molest.”

“In a short time the Roman legions will invest Carthage, under the guidance of those same deities who enabled them in the former war to take vengeance for the breach of treaties. Are you strangers to that enemy, or to yourselves, or so the fortune attending both nations? When ambassadors came from, allies, in favor of allies, your worthy general, disregarding the law of nations, refused them admittance into his camp. Nevertheless, after meeting a repulse, where ambassadors, even from enemies, are not refused access, they have come to you, requiring satisfaction in conformity to treaty. They charge no crime on the public, but demand the author of the transgression, the person answerable for the offence. The more moderation there appears in their proceedings, and the slower they are in beginning a warfare, so much the more unrelenting, I fear, will prove the fury of their resentment when they do begin.”

“Place before your eyes the islands Ægates and Eryx, the calamities which you underwent on land and sea, during the space of twenty-four years; nor were your troops then led by this boy, but by his father Hamilcar, another Mars, as those men choose to call him. But at that time we had not, as we were bound by treaty, avoided interfering with Tarentum in Italy, as at present we do not avoid interfering with Saguntum. Wherefore gods and men united to conquer us, and the question which words could not determine, ‘Which of the nations had infringed the treaty?’ the issue of the war made known, as an equitable judge, giving victory to that side on which justice stood.”

“Hannibal is now raising works and towers against Carthage; with his battering rams he is shaking the walls of Carthage. The ruins of Saguntum (oh! that I may prove a false prophet!) will fall on our heads: and the war commenced against the Saguntines must be maintained against the Romans. Some will say, ‘Shall we then deliver up Hannibal?’ I am sensible that, with respect to him, my authority is of little weight, on account of the enmity between me and his father. But as I rejoiced at the death of Hamilcar, for this reason, that had he lived, we should now have been embroiled in a war with the Romans, so do I hate and detest this youth as a fury and a firebrand kindling the like troubles at present.”

“Nor is it my opinion, merely, that he ought to be delivered up, as an expiation for the infraction of the treaty, but that, if no one demanded him, he ought to be conveyed away to the remotest coasts, whence no accounts of him, nor even his name, should ever reach us, and where he would not be able to disturb the tranquillity of our state. I therefore move you to resolve that ambassadors be sent instantly to Rome, to make apologies to the senate; others, to order Hannibal to withdraw the troops from Saguntum, and to deliver up Hannibal himself to the Romans, in conformity to the treaty; and that a third embassy be sent, to make restitution to the Saguntines.”

When Hanno had ended his discourse, there was no occasion for any one to enter into a debate with him, so entirely were almost the whole body of the senate in the interest of Hannibal, and they blamed him as having spoken with greater acrimony than even Valerius Flaccus, the Roman ambassador. They then answered the Roman ambassadors that ‘the war had been begun by the Saguntines, not by Hannibal; and that the Roman people acted unjustly and unwisely, if they preferred the interest of the Saguntines to that of the Carthaginians, their earliest allies.’

11. While the Romans wasted time in sending embassies, Hannibal finding his soldiers fatigued with fighting and labor, gave them a few days to rest, appointing parties to guard the machines and works. This interval he employed in reanimating his men, stimulating them at one time with resentment against the enemy, at another, with hope of rewards; but a declaration which he made in open assembly that, on the capture of the city, the spoil should be given to the soldiers, inflamed them with such ardor that, to all appearance, if the signal had been given immediately, no force could have withstood them.

The Saguntines, as they had for some days enjoyed a respite from fighting, neither offering nor sustaining an attack, so they had never ceased, either by day or night, to labor hard in raising a new wall, in that part where the city had been left exposed by the fall of the old one. After this the operations of the besiegers were carried on with much greater briskness than before; nor could the besieged well judge, whilst all places resounded with clamors of various kinds, to what side they should first send succor, or where it was most necessary. Hannibal attended in person, to encourage a party of his men who were bringing forward a movable tower, which exceeded in height all the fortifications of the city.

As soon as this had reached the proper distance, and had, by means of the engines for throwing darts and stones, disposed in all its stories, cleared the ramparts of all who were to defend it, then Hannibal, seizing the opportunity, sent about five hundred Africans, with pick-axes, to undermine the wall at the bottom; which was not a difficult work, because the cement was not strengthened with lime, but the interstices filled up with clay, according to the ancient method of building: other parts of it therefore fell down, together with those to which the strokes were applied, and through these breaches several bands of soldiers made their way into the city. They likewise there took possession of an eminence, and collecting thither a number of engines for throwing darts and stones, surrounded it with a wall, in order that they might have a fortress within the city itself, a citadel, as it were, to command it.

The Saguntines on their part raised an inner wall between that and the division of the city not yet taken. Both sides exerted themselves to the utmost, as well in forming their works as in fighting. But the Saguntines, while they raised defences for the inner parts, contracted daily the dimensions of the city. At the same time the scarcity of all things increased, in consequence of the long continuance of the siege, while their expectations of foreign aid diminished; the Romans, their only hope, being at so great a distance, and all the countries round being in the hands of the enemy. However, their sinking spirits were for a short time revived by Hannibal setting out suddenly on an expedition against the Oretans and Carpetans: for these two nations, being exasperated by the severity used in levying soldiers, had, by detaining the commissaries, afforded room to apprehend a revolt; but receiving an unexpected check, from the quick exertions of Hannibal, they laid aside the design of insurrection.

12. In-the mean time the vigor of the proceedings against Saguntum was not lessened; Maharbal, son of Himilco, whom Hannibal had left in the command, pushing forward the operations with such activity, that neither his countrymen nor the enemy perceived that the general was absent. He not only engaged the Saguntines several times with success, but, with three battering-rams, demolished a considerable extent of the wall; and when Hannibal arrived he showed him the whole ground covered with fresh ruins. The troops were therefore led instantly against the citadel; and after a furious engagement, in which great loss was suffered on both sides, part of the citadel was taken.

Small as were the hopes of an accommodation, attempts were now made to bring it about by two persons; Alcon, a Saguntine, and Alorcus, a Spaniard. Alcon, thinking that he might effect something by submissive entreaties, went over to Hannibal by night, without the knowledge of the Saguntines; but his piteous supplications making no impression, and the terms offered by his enemy being full of rigor, and such as might be expected from an enraged and not unsuccessful assailant, instead of an advocate lie became a deserter; affirming, that if any man were to mention to the Saguntines an accommodation on such conditions, it would cost him his life; for it was required that they should make restitution to the Turdetans; should deliver up all their gold and silver; and, departing from the city with single garments, should fix their residence in whatever place the Carthaginian should order.

When Alcon declared that his countrymen would never accept these conditions of peace, Alorcus, insisting that when men's bodily powers are subdued, their spirits are subdued along with them, undertook the office of mediator in the negotiation. Now he was at this time a soldier in the service of Hannibal, but connected with the state of Saguntum in friendship and hospitality. Delivering up his sword to the enemy’s guards, he passed openly through the fortifications, and was conducted at his own desire to the pretor. A concourse of people of every kind having immediately assembled about the place, the senate, ordering the rest of the multitude to retire, gave audience to Alorcus, who addressed them in this manner:

13. ‘If your countryman Alcon, after coming to the general to sue for peace, had returned to you with the offered terms, it would have been needless for me to have presented myself before you, as I would not appear in the character either of a deputy from Hannibal, or of a deserter. ‘But since he has remained with your enemy, either through his own fault, or yours: through his own, if lie counterfeited fear; through yours, if he who tells you truth is to be punished: I have come to you, out of my regard to the ties of hospitality so long subsisting between us, in order that you should not be ignorant that there are certain conditions on which you may obtain both peace and safety. Now, that what I say is merely out of regard to your interest, and not from any other motive, this alone is sufficient proof: that, so long as you were able to maintain a defence by your own strength, or so long as you had hopes of succor from the Romans, I never once mentioned peace to you.’

‘Now, when you neither have any hopes from the Romans, nor can rely for defence either on your arms or walls, I bring you terms of peace, rather unavoidable than favorable. And there may be some chance of carrying these into effect, on this condition, that, as Hannibal dictates them, in the spirit of a conqueror, so you should listen to them with the spirit of men conquered: that you consider not what you part with as loss, for all things are the property of the victor, but whatever is left to you as a gift.’

‘The city, a great part of which is already demolished, and almost the whole of which he has in his possession, he takes from you; your lands he leaves to you, intending to assign a place where you may build a new town: all your gold and silver, both public and private property, he orders to be brought to him: your persons, with those of your wives and children, he preserves inviolate, provided you are satisfied to quit Saguntum without arms, and with single garments. These are the terms which, as a victorious enemy, he enjoins: with these, grievous and afflicting as they are, your present circumstances counsel you to comply. I do not indeed despair but that, when the entire disposal of every thing is given up to him, he may remit somewhat of the severity of these articles. But even these, I think it advisable to endure, rather than to suffer yourselves to he slaughtered, and your wives and children seized and dragged into slavery before your eyes, according to the practice of war.’

14. The surrounding crowd, gradually approaching to hear this discourse, had formed an assembly of the people conjoined with the senate, when the men of principal distinction, withdrawing suddenly before any answer was given, collected all the gold and silver both from their private and public stores, into the forum, threw it into a tire hastily kindled for the purpose, and then most of them cast themselves headlong in after it. While the dismay and confusion which this occasioned filled every part of the city, another uproar was heard from the citadel. A tower, after being battered for a long time, had fallen down, and a cohort of the Carthaginians having forced their way through the breach, gave notice to their general that the place was destitute of the usual guards and watches.

Hannibal, judging that such an opportunity admitted no delay, assaulted the city with his whole force, and instantly making himself master of it, gave orders that every person of adult age should be put to the sword: which cruel order was proved, however, by the event, to have been in a manner induced by the conduct of the people ; for how could mercy have been extended to any of those who, shutting themselves up with their wives and children, burned their houses over their heads; or who, being in arms, continued fighting until stopped by death?

15. In the town was found a vast quantity of spoil, notwithstanding that the greater part of the effects had been purposely injured by the owners; and that, during the carnage, the rage of the assailants had made hardly any distinction of age, although the prisoners were the property of the soldiers. Nevertheless, it appears that a large sum of money was brought into the treasury out of the price of goods exposed to sale, and likewise that a great deal of valuable furniture and apparel was sent to Carthage.

Some writers have asserted that Saguntum was taken in the eighth month from the beginning of the siege; that Hannibal then retired into winter-quarters to New Carthage; and that, in the fifth month, after leaving Carthage, he arrived again in Italy. But if these accounts were true, it is impossible that Publius Cornelius and Tiberius Sempronius could have been the consuls, to whom, in the beginning of the siege, the ambassadors were sent from Saguntum; and who, during their office, fought with Hannibal; the one at the river Ticinus, and both, a considerable time after, at the Trebia.

Either all these matters must have been transacted in less time, or Saguntum must have been taken, not first invested, in the beginning of that year wherein Publius Cornelius and Tiberius Sempronius were consuls: for the battle at the Trebia could not have happened so late as the year of Cn. Servilius and Caius Flaminius; because Caius Flaminius entered on the office of consul at Ariminum, having been elected thereto by Tiberius Sempronius, who, after the engagement at the Trebia, had gone home to Rome for the purpose of electing consuls ; and when the election was finished, returned into winter-quarters to the army.

16. The ambassadors returning from Carthage, brought information to Rome that every thing tended to war; and nearly at the same time news was received of the destruction of Saguntum. Grief seized the senate for the deplorable catastrophe of their allies; and shame for not having afforded them succor; rage against the Carthaginians, and such apprehensions for the public safety, as if the enemy were already at their gates; so that their minds being agitated by so many passions at once, their meetings were scenes of confusion and disorder, rather than of deliberation: for ‘never,’ they observed, ‘had an enemy more enterprising and warlike entered the field with them; and at no other period had the Roman power been so unfit for great exertions, or so deficient in practice. As to the Sardinians, Corsicans, Istrians, and Illyrians, they had only roused the Roman arms without affording them exercise; and with the Gauls the affair was really a tumult, rather than a war.

The Carthaginians, another kind of foe, were crossing the Iberus; trained to arms during twenty-three years, in the most laborious service, among the nations of Spain; accustomed to conquer on every occasion; habituated to the command of a most able general; flushed with their late conquest of a very opulent city, and bringing with them many Spanish states; while the Gauls, ever glad of an opportunity of fighting, would doubtless be engaged in the expedition. War must then be waged against all the world, in the heart of Italy, and under the walls of Rome.

17. The provinces had been already named for the consuls, but now they were ordered to cast lots. Spain fell to Cornelius; Africa, with Sicily, to Sempronius. For the service of the year six legions were decreed, with such a number of the troops of the allies as the consuls should deem requisite, and a fleet as great as could be fitted out. Of Romans were enlisted twenty-four thousand foot, and one thousand eight hundred horse; of the allies, forty thousand foot, and four thousand four hundred horse. The fleet consisted of two hundred and twenty ships of five banks of oars, and twenty light galleys. The question was then proposed to the people, whether ‘they chose and ordered that war should be declared against the people of Carthage?’ This being determined on, a general supplication was performed in the city, and prayers offered to the gods, that the war which the Roman people had ordered might have a prosperous and a happy issue.

The forces were divided between the consuls in this manner: to Sempronius were assigned two legions, containing each four thousand foot and three hundred horse, and of the allies sixteen thousand foot and one thousand eight hundred horse, with one hundred and sixty ships of war, and twelve light galleys. With these land and sea forces Tiberius Sempronius was sent to Sicily, with intention that he should cross over to Africa, in case the other consul should be able to prevent the Carthaginians from entering Italy. The army assigned to Cornelius was less numerous, because Lucius Manlius, a pretor, was also sent into Gaul with a considerable force.

Of ships, particularly Cornelius’ share was small: sixty quinqueremes only were givert him, for it was not supposed either that the enemy would come by sea, or that he would exert himself on that element.

Two Roman legions, with their regular proportion of cavalry, and of the allies fourteen thousand foot and sixteen hundred horse were assigned to him. In this year the province of Gaul, though not yet threatened with a Carthaginian war, had posted in it two Roman legions, and ten thousand confederate infantry, with one thousand confederate horsemen and six hundred Roman.

18. These adjustments being made, they yet determined, previous to the taking up arms, to send Quintus Fabius, Marcus Livius, Lucius Æmilius, Caius Licinius, and Quintus Baebius, men venerable on account of their age, into Africa, as ambassadors, to require an explanation from the Carthaginians, whether Hannibal’s attack on Saguntum had been authorised by the state; and in case they should acknowledge it, as it was expected they would, and defend that proceeding, then to declare war against the people of Carthage.

When the Romans arrived at Carthage, and were introduced to an audience of the senate, Quintus Fabius, without enlarging on the subject, simply proposed the question as stated in their instructions; on which one of the Carthaginians replied, ‘Romans, in your former embassy you were too precipitate, when you demanded that Hannibal should be delivered up, as attacking Saguntum of his own authority. But your present proceeding, though hitherto milder in words, is, in effect, more unreasonably severe.’

‘A charge was made against Hannibal, only when you required him to be delivered up: now you endeavor to extort from us a confession of wrong committed, and at the same instant, as if we had already pleaded guilty, insist on reparation. For myself, I am of opinion that the question proper to be asked is, not whether Saguntum was attacked by public authority or private, but whether justly or unjustly? for with respect to a subject of our government, whether acting under direction of the public authority, or not, the right of inquiry, and of punishing, is exclusively our own.’

‘The only point, then, that comes into discussion with you is, whether the act was allowable according to treaty? Wherefore, since you chose that a distinction should be made between what commanders do by public authority, and what of their own will, there is a treaty subsisting between us, concluded by your consul Lutatius, in which provision is made for the interest of the allies of both nations. But there is no clause in favor of the Saguntines; for they were not at the time in alliance with you. But then, in the treaty entered into with Hasdrubal, the Saguntines are expressly exempted from hostilities. In answer to which, I shall urge nothing but what I have learned from yourselves: for you asserted that the treaty which your consul Caius Lutatius at first concluded with us, inasmuch as it had been concluded without either the approbation of the senate, or an order of the people, was not binding on you; and that for that reason another treaty was ratified anew, under the sanction of public authority. Now if your treaties do not bind you, unless sanctioned by your approbation and order, surely the treaty of Hasdrubal, under the same circumstances, cannot be binding on us. Cease therefore to talk of Saguntum, and the Iberus; and let your minds at length give birth to the burden of which they are long in labor.’

The Roman then, folding up a corner of his robe, said, ‘Here we bring you peace, and war; take which you choose.’ Which proposal they answered with an equal degree of peremtory heat, calling out, that ‘he should give whichever he chose.’ He then threw open the fold again, and said that ‘he gave war:’ they with one voice replied, that ‘they accepted it; and with the same spirit with which they accepted it, would prosecute it.’

19. This mode of a direct demand and declaration of war was deemed suitable to the dignity of the Roman people, even before this time, but more particularly after the destruction of Saguntum, than to enter into a verbal disquisition concerning the construction of treaties: for if the business were to be decided by argument, what similitude was there between the treaty of Hasdrubal and the former treaty of Lutatius, which was altered? Since in the latter there was an express clause inserted, that it should be valid, provided the people should ratify it but in that of Hasdrubal there was no such provision.

Besides, this treaty was confirmed in such a manner by the silent approbation of so many years, during the remainder of his life, that even after the death of its author no alteration was made in it; although, even were the former treaty adhered to, there was sufficient security provided for the Saguntines, by the exempting from hostilities the allies of both nations, there being no distinction made of those who then were, or of those who should afterwards become such. And, as it was evidently allowable to form new alliances, who could think it reasonable, either that persons should not be received into friendship on account of any degree of merit whatever; or, that people, once taken under protection, should not be defended?

The only restriction implied was, that the allies of the Carthaginians should not be solicited to revolt, nor, revolting of their own accord, should be received. The Roman ambassadors, in pursuance of their instructions received at Rome, passed over from Carthage into Spain, in order to make application to the several states of that country, and either to engage their alliance, or at least to dissuade them from joining the Carthaginians.

They came, first to the Bargusian, by whom being favorably received because that people were dissatisfied with the Carthaginian government, they roused the spirits of many powers on the farther side of the Iberus by the flattering prospect of a change in their circumstances. Thence they came to the Volscians, whose answer, which was reported with applause through every part of Spain, deterred the other states from joining in alliance with Rome. For thus the oldest member of their assembly replied, ‘Where is your sense of shame, Romans, when you require of us that we should prefer your friendship to that of the Carthaginians? The Saguntines, who embraced it, have been abandoned by you: in which abandonment you, their allies, have shown greater cruelty than the Carthaginians, their enemy, showed in destroying them. What I recommend is, that you seek connexions where the fatal disaster of Saguntum is unknown. To the states of Spain the ruins of that city will be both a melancholy and forcible warning, not to confide in the faith or alliance of Rome.’ They were then ordered to depart immediately from the territories of the Yolscians; nor did they afterwards meet from any assembly in Spain a more favorable reception; therefore, after making a circuit through all parts of that country without effecting any thing, they passed over into Gaul.

Livy. Livy, vol III. translated by George Baker, A. J. Valpy, 1833.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.