Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

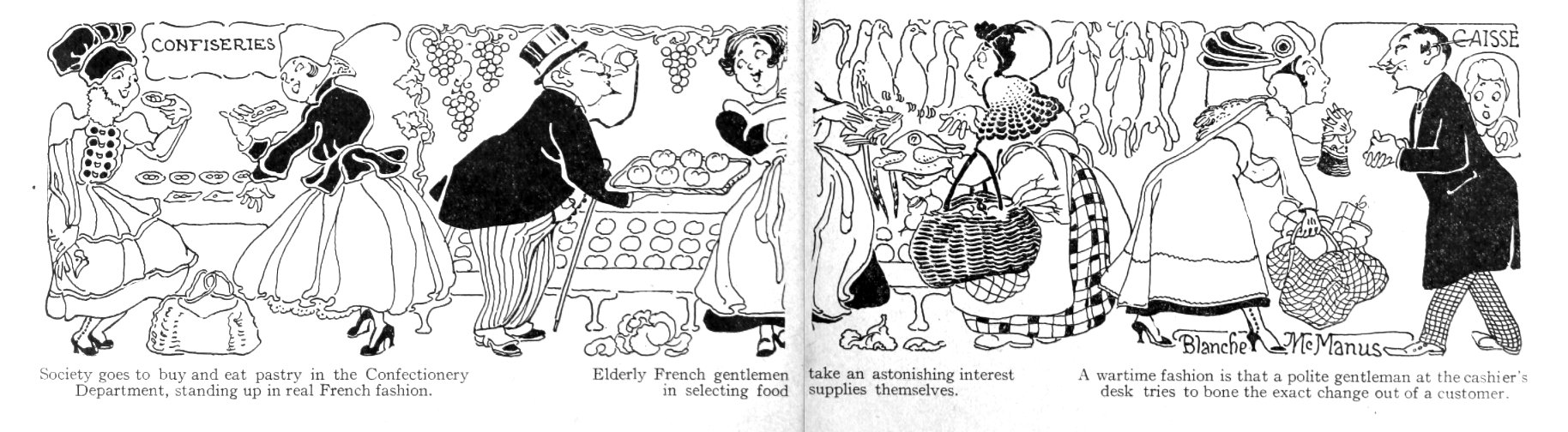

“Standing in the Food Line in Paris,” by Blanche McManus from American Cookery, Volume 21, 1916.

Standing in the food line in Paris is both an amusing and an aggravating period of the feminine day's work. Don't make the mistake of thinking that this means getting something for nothing in these necessitous war times. It only indicates the way we have to shop in the super-groceries of Paris at all times; that is, we get into line and await our turns, as is the Paris grocery fashion, and like all Paris fashions it is entirely peculiar and unique unto itself. It is as if you were buying a ticket. It is a meal-ticket, in fact, that costs double what it once did and the Frenchwoman, most careful and conscientious of housekeepers, fairly raves over the present food-prices which have jumped fifty to a hundred percent since the war has tangled up her housekeeping routine.

For the super-grocery itself, it has been a sunshiny period of more than usual opulence in profits. There are half a dozen of these super-groceries in Paris, each with establishments distributed in various parts of the city, and in some cases branch houses throughout the country, all co-operating to the general end. The peculiarity is that these establishments are really grocery-markets, and besides they are in most cases actual manufacturers, or assemblers, of most of the products which they sell.

It is the department store idea applied to the selling of food with unusual elaboration, and as a result it has brought every style of eatable together in one store from the de luxe can and package goods, through meats, to fruits and vegetables, so that the French-woman can do her day's buying of provisions under one roof.

Remaining images from text.

The mixed character of the super-grocery makes for a curious mixture of inconvenience and luxuriousness. Their installation tends towards both hygienic and ornamental effects, usually of white marble and tiling with much plate glass and effective brass and nickel finishings, while elaborate, symbolically designed friezes decorate the walls of the various departments with pleasing effect. Meanwhile the floors are strewn with fine sawdust, which is brushed, up frequently, after the homely, but efficient provincial French fashion of keeping floors clean.

While the grocery department proper has an imposing facade of plate glass windows and doors they are something in the nature of stage-scenery, as the remainder of the store is practically arcaded entrances, which stay open winter and summer to accommodate the crowds that surge in and out. There is yet another anomaly for most have installed perfectly appointed tea-rooms.

But the greatest peculiarity of the super-grocery-market is its method of doing business, and this results in the food-line. There is nothing in the way of the usual counter, only long table-like shelves on which the varied comestibles are laid out, each ticketed with its price, as on a bargain counter in a department store, nor are there any stools or chairs in the place. You may walk around and inspect the goods at your leisure and no one will disturb you by coming up and demanding what you wish to buy.

The smartly attired floorwalker is non-existent, also the black-coated shop clerk. Instead, there are young men in long white working blouses and active young women wearing business-like aprons, all rushing about but paying not the slightest attention to you. This is bewildering to a stranger to the customs.

In this way you begin your personally conducted trip after food. Instead of going to a counter to be waited on, you take your place at the end of a long line of waiting customers beside a railing in front of one of the cashier's desks, of which there is one for each department. The universal rule of the French department store of whatever nature is that the customer herself pays at the desk.

You wait while each clerk brings her customer up to the desk, sees that she pays her bill and hands her her parcel. As the clerk finishes with her customer, she picks another one from the waiting line. As your turn comes you tell the young woman clerk what it may be that you wish to purchase and then meekly follow her from counter to counter and help her to find it. When she has succeeded in collecting together all the articles which you may have wanted from the department, she brings you up to a double wrapping-table where there is already collected a struggling mass of women shoppers, each trying to keep track of her individual clerk and purchases, which principally results in blocking the way of the workers.

In the melee you stick as best you can to the clerk's elbow as she calls off your order to be checked up by the head controller. After which your young woman leisurely hunts up wrapping paper and twine in which to do up your parcel, in such a casual way, too, that the chances are it falls apart before you get it home. The inability of the French shop employee to tie up properly a parcel, is almost a national failing and comes from generations of a lack of training in this art, caused by the habit of the Frenchwoman of all classes to go food-shopping with a market basket, or a large net bag, called a filet, on her arm in which to carry home her purchases.

Back of this stands the French fetish of economy as practised by the little grocery, which neither wraps up nor delivers its customers' parcels. Its limit of indulgence in this line is to hand out a client's sugar or salt loosely laid in a piece of last year's newspaper, bought of junk dealers especially for this purpose.

It was one of the big innovations in the business of food, when the super-grocery introduced the chic style of doing up a customer's purchases in stout and presentable brown paper parcels, while it was considered on a par with a revolution when it instituted still more recently the function of the delivery of parcels. In spite of which the bulk of the customers still bring their basket, or filet, not only because the French-woman clings to old customs, but for the reason that even the super-grocery will not make deliveries of goods under the value of ten francs—a method of business that would surely chill patronage in America.

When your white-aproned young woman does hand you your parcel, it is with the stern injunction to have your exact change ready. This is an irritating imposition, which the super-grocery especially perpetrates on its clients, a result of the rarity of small change in France since the beginning of war, caused by nervous people hoarding their silver and copper coins.

Finally, you complete your circular tour by returning to the same desk from which you started, here to pay your bill, where a man stands by to check off the amount and see that the cashier gives out the correct change. At last, the young woman clerk can wash her hands of you and is at liberty to behead once more the waiting line of foodhunters of another customer.

This method of forming the food-line is a little too dilettante in its action for the spritely American taste, but the French-woman adores any plan that bristles with inconveniences, as it makes her feel that she is very busy, and the advantage of the system is that it has broken her of the bad habit of crowding in ahead of her turn. The greatest disadvantage of the food-line from point of time is that it must be formed anew, and the same lengthy operations gone through with, for each of the various departments.

For example: you may have made your first circular tour in the grocery department proper, which occupies the front of the establishment. Then you decide to supplement your luncheon purchases with one of the plats du jour, from the list of daily dishes prepared by the store. You pass through a highly ornamental plate-glass and iron-grilled barrier into the department of these ready made dishes, which are made up and in most cases, also, partially cooked.

This idea of making up a menu of ready-made dishes was originated by the Paris super-grocery, and while it is a sort of delicatessen formula (only do not whisper such a German word into French ears), it has been by the grocery-market developed beyond the limits conceived by any other purveyor of prepared dishes. Ranged on marble tables there are, beside the usual cold meats and salads, a number of the standard dishes of the French dejeuner, substantial meat entrees, each garnished with its correct vegetable and accompanying sauce. They have already been cooked in earthenware dishes and only need to be popped into the home oven and heated up ready for the table.

The ready-made dish department is not only a repository of ease for the studio housekeeper of the Latin Quarter, and for the home maker of the kitchenette apartment, but is also patronized by the thrifty French bourgeoise who finds these dishes, which can be bought for such reasonable prices, from twenty to fifty cents each, are really far cheaper than she can make the same things for at home, with all trouble extracted, and then there is a rebate of five or ten cents on each crockery receptacle.

The selling of meat is specialized to a high degree in France. Pork is only sold at a charcutier, poultry and game in the shop of the marchand de volatile et gibier; beef, veal and mutton only are linked up at the boucherie. Even now that the super-grocery-market has introduced the food department store, it still bows to tradition and divides up, its meat department into four sections, which means for each one waiting again in the food line. It is always a long line that trails through the charcuterie department, which shows up the importance of pork products in the French scheme of food. It is not, however, for the fresh pork carcasses that hang there, that the crowd surges in, but for the de luxe forms of the porcine, which take rank among the choicest "hors-d'oeuvres" with which the French begin each luncheon and dinner, and their name is legion.

In natural sequence now the food-line forms in the regular meat department, finished as all the others in white marble with saw-dusted floors of the same material. You dodge about among serried rows of fresh-butchered beeves, muttons and veals hanging from nickeled hooks above your head. Here another style of food is in vogue. Spread out on marble counters is an array of various cuts,—steaks, roasts, chops and the like—trimmed, trussed, boned and prepared for cooking, each marked with its fixed price.

This ready-prepared system saves the making up of dilatory feminine minds as well as the time of employees during the rush hours; as the super-grocery claims to sell cheaper than the small dealer, everything must in consequence be figured down to the economic low level. So it is you may leisurely inspect the bargains displayed, make your choice and then, as often happens, take your place in the waiting line only to see someone ahead of you choose the very morsel upon which you have set your eyes and mind. This is the gamble of the food-line.

Such is the war time dearth of men that it is a young woman butcher who wields the cleaver at the chopping block, with, it must be confessed, less skill than her male prototype. Any complaint, however, will be stifled when your eye catches sight of one of the rather pathetic signs posted about, that politely requests customers to be considerate towards the young women in their arduous, adopted duties. Serving in the super-grocery is one of the many new occupations that war has opened to the women of France.

About the time that the super-grocery was established in the mid-nineteenth century the guild of Paris butchers was limited by their charter to only a very few members. These became so arrogant and wealthy that one of their number, on the occasion of a public procession, cut in ahead of the King's own carriage, whereupon, the whole of the trade was punished for the scandal; the business of butchering, then a close corporation, being thrown open to all.

This is as the story goes. But there is no doubt about the arrogant position of the Paris butcher today with the price of meat double in many instances what it was before the war. Yet it is claimed to be the most precarious of all food business and for this reason it was with timidity, originally, that the super-grocery installed its fresh meat department. Today it is one of their great successes owing to their large way of handling it.

Quite as timidly the super-grocery put on sale recently, for the first time in its history, cold storage meats and the sign now decorates the front of some of their stores, ''Viande importee congelee'' and marks what is perhaps the most revolutionary departure yet in the food business of France. The French have been bitterly opposed to the introduction of refrigerator meats, their prejudice was simply the result of never having tasted them, but now that the super-grocery has taken them up the Parisians will doubtless take to the congelee steaks and roasts with the same docility that they have displayed towards other of the super-grocery innovations. Already they have nicknamed the cold storage meat "frigo."

The crowning triumph of the super-grocery's policy is the fish department. Its importance in the scheme of food may be estimated, when it is realized that the exclusive retail fish shop does not exist in Paris. Only in the large general open-air market, held bi-weekly on some boulevard of her quarter, will the Parisian housekeeper be able to buy her fish from a few stalls selling fresh fish, which lie gasping on dry boards without ice. Or it may be that her neighboring greengrocer will put a few unappetising fish of the "remainder class" on sale on Fridays and holidays as a special favor to his clients. In both cases prices are ridiculously high, when it is considered that two thirds of France's frontiers are salt water. Sea-food is therefore the scarcest and dearest article of consumption on the French menu.

The super-grocery-market has been thus almost philanthropic in bringing fish into range of the daily steps and average purse of the Paris housewife. The fish department has been featured in a spectacular manner worthy of its exotic importance as a novelty. It is usually to be found installed in a separate division of the store, marble throughout, while the walls are tastefully and ornately decorated with gay-colored friezes, or comprehensive mural embellishments of tiles, or in porcelain relief, whose motifs comprise a long range of aquatic subjects from quaintly picturesque fishing craft to the more spectacular members of the finny tribes, all twined about in arabesques of gilded seaweed.

The fish themselves are ranged on morgue-like marble slabs bedded on green water weeds over which trickles water. Ice is such a super-luxury in France that not even the super-grocery has arisen to the need of it for its fish department. True, they have installed some forms of meat refrigerators, but of a baby size and a temperature far from freezing. They depend upon keeping things fresh by the circulation of air only, for this reason the stores stay open all day and at night are protected by grilled barriers and not closed shutters.

The clou of the fish department is the aquarium which rises in two or three ornamental tiers of marble and glass and encloses the stocks of sporty brook and mountain trout and other freshwater fish, with perhaps a purely decorative basin containing gold fish. On platters of porcelain are piled up the small shell fish, the numerous and much sought after coquillages, which also figure importantly in the long list of hors d'oeuvres.

For poultry and game one must go outside where the stalls are lined up on the sidewalks in front of the store, partly protected by overhead awnings. The poultry is invariably dressed, while the game is almost exclusively composed of pheasants, hares and rabbits. On the sidewalk are also the fruits and vegetables, so is the cashier's desk for all of these outside departments; but the food-line is not formed out here, possibly for lack of space.

For a study of the idiosyncrasies of a Paris shopping crowd, there is no better method than by waiting in the food-line. The woman economical of time comes between eight, and ten; the bonnes, servant maids, bareheaded, white-aproned with baskets, form interminable lines before the noon hour; society comes in the afternoon to buy and eat, standing on the spot as is the custom, some delicacy in the pastry division, or as an excuse for a cup of tea in the attractive tea-room, which is apt to be the central feature of the confectionery department.

The elderly Parisian man is quite an habitue of the super-grocery, being a "rentier" usually, he has time and also, no matter what his position in life, he takes an astonishing amount of personal interest in the details of his food consumption. For this reason elderly aristocratic gentlemen will be seen at unexpected hours selecting with greatest care say, a semelle of fine fruits for the dinner's dessert, which are luxuriously bedded in cotton, on a flat wicker tray, in dozens and half-dozens, an invention of the super-grocery, whose innovation also has been the selling of choice fruits by piece instead of weight.

Two-thirds of the food-line is returning bottles, plates, jars and all sorts of odd crockery that are "taken back," after first having been charged on the original purchase. From two to ten cents is charged back on each piece. It would be impossible to imagine the American woman taking back an armful of rough crockery in her shopping round even for a rebate on her next purchase, but the thrifty Frenchwoman eternally occupies herself with the chase of the sou.

But the two great innovations inaugurated by the super-groceries are first: selling at the cours du jour—the ruling prices of the day—keeping, however, for the store the same margin of profits. The trade before this had been in the habit of making the customer pay all that the traffic would stand. The second, was to introduce into the business the hitherto unknown feature of fixed prices, thus doing away, too, with the pernicious graft of one, cent in every twenty cents to which all servants in France consider themselves entitled when they purchase for their employers. This "dance of the basket," as it is called, still is practised in the small shops as well as in the open-air markets of France.

The true success of the super-grocery in Paris has been, however, based on the policy of being its own chef, its own chemist and as far as possible the manufacturer of its own stock in trade. The largest of these super-groceries has five retail establishments in Paris, its own slaughter house in the Paris wholesale meat market and three great food manufacturies and storage warehouses in the suburbs, as well as one hundred and fifty affiliated groceries all over France, selling their exclusive manufactured products.

The firms are vineyard owners in all the celebrated vine growing regions of France, Algeria and Tunisia. They make no-end lists of sweet syrups, so much used by the French for soft drinks. They have, too, their own bakery, producing crackers, pastry and confectionery. Their agents all over the countryside buy up fresh fruits and vegetables, not only for their retail stores but for the preserving and canning of their own goods. They also put up pickles, condiments and mustards bearing their own brand. They grow, some at least, of their own beet-root and refine and put up their own sugars and salt.

Paris is, however, and probably will always remain, a city of small shops and the French as a nation are advocates and partisans of the small shopkeeper. Hence it has taken the great war, which has proved out so many issues, to prove out to the still sceptical Parisians the real utility of handling food on a large scale. The only fear that war has provoked in the hearts of the dwellers of Paris is the fear of running short of food, as in their memories still linger the horrors of the starvation siege of their city in the last war of the "seventies;" consequently there have been periodical "rushes" on the grocery shops by Parisians, as well as suburbanites, to buy up and stow away stocks of provisions, when German advances on Paris have seemed imminent during the last year and a half of warfare.

In these crises there were days at a time when such staples as sugar, salt, potatoes, etc., were often entirely lacking at the small specialist epicerie with its antiquated facilities and restricted ways of doing business, and could only be gotten at the super-grocery. Then it was that for weeks on end the "food-lines" in the super-groceries were running over into the streets for blocks around; people waited their turn for days; the police had to form the "service of order" while the delivery wagons of the establishments were kept going night and day between their warehouses and retail stores replenishing their rapidly depleted stocks. Then it was that the eyes of the Parisian food shoppers were opened wide at last to the advantages of modern methods and efficiency in the distribution of a city's food supply.

The super-groceries of Paris by their policy of manufacturing to so great an extent their own food ammunition and controlling their own depots of supplies and, finally, by mobilizing their forces efficiently, demonstrated their value, at the most critical period in the history of their city, to the Parisians, the most sceptical people on earth, of any departure from their old traditions, and at the same time rolled up to their own credit golden opinions and golden dividends. The enormous profits reaped by the super-groceries of Paris from their "war boom" can only be guessed.

McManus, Blanche. “Standing in the Food Line in Paris.” American Cookery, 1916.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.