Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Elements of Culture in Native California by Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1922.

Boats

Native California used two types of boat: the wooden canoe and the tule balsa, a shaped raft of rushes. Their use tends to be exclusive without becoming fully so. Their distribution is determined by cultural more than by physiographic factors.

The northwestern canoe was employed on Humboldt bay and along the open, rocky coast to the north, but its shape as well as range indicate it to have been devised for river use. It was dug out of half a redwood log, was square ended, round bottomed, of heavy proportions, but nicely finished with recurved gunwales and carved-out seat. A similar if not identical boat was used on the southern Oregon coast beyond the range of the redwood tree. The southern limit is marked by Cape Mendocino and the navigable waters of Eel river. Inland, the Karok and Hupa regularly used canoes of Yurok manufacture, and occasional examples were sold as far upstream as the Shasta.

The southern California canoe was a seagoing vessel, indispensable to the Shoshonean and Chumash islanders of the Santa Barbara group, and considerably employed also by the mainlanders of the shore from Point Concepcion and probably San Luis Obispo as far south as San Diego. It was usually of lashed planks, either because solid timber for dugouts was scant, or because dexterity in woodworking rendered a carpentered construction less laborious. A dugout form seems also to have been known, and perhaps prevailed among the manually clumsier tribes toward San Diego. A double-bladed paddle was used. The southern California canoe was purely maritime. There were no navigable rivers, and on the few sheltered bays and lagoons the balsa was sufficient and generally employed. The size of this canoe was not great, the beam probably narrow, and the construction light; but the sea is normally calm in southern California and one side of the islands almost always sheltered.

A third type of canoe had a limited distribution in favorable localities in northern California, ranging about as far as overlay twining, and evidently formed part of the technological culture characteristic of this region. A historical community of origin with the northwestern redwood canoe is indubitable, but it is less clear whether the northeastern canoe represents the original type from which the northwestern developed as a specialization, or whether the latter is the result of coastal influences from the north, and the northeastern form a deteriorated marginal extension. This northeastern canoe was of pine or cedar or fir, burned and chopped out, narrow of beam, without definite shape. It was made by the Shasta, Modoc, Atsugewi, Achomawi, and northernmost Maidu.

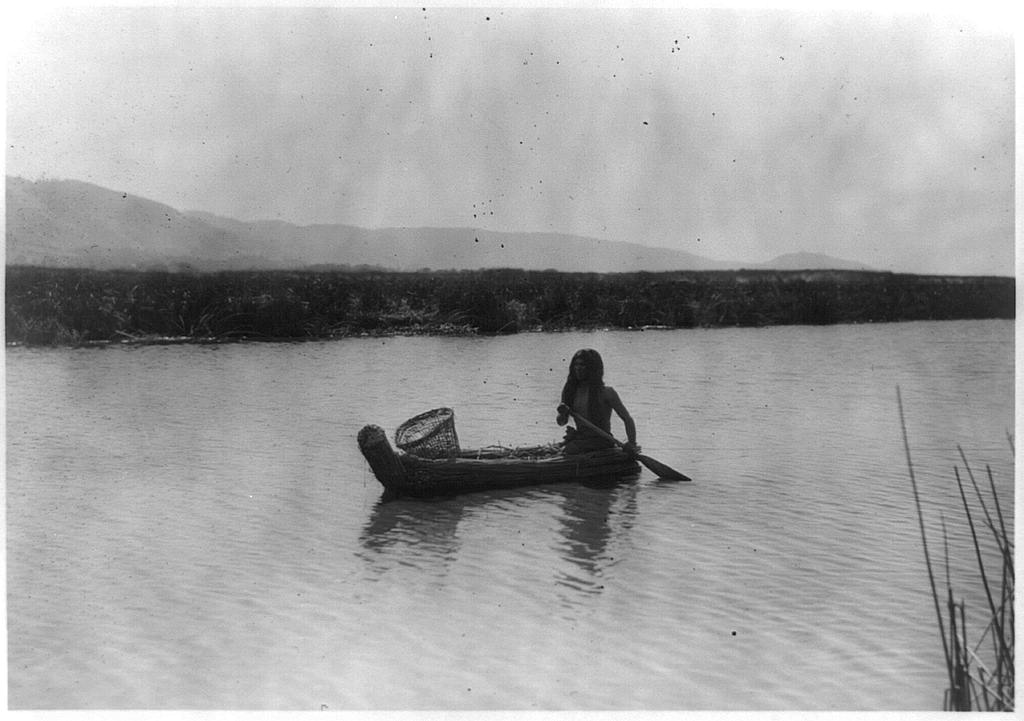

The balsa or rush raft had a nearly universal distribution, so far as drainage conditions permitted; the only groups that wholly rejected it in favor of the canoe being the Chumash and the northwestern tribes. It is reported from the Modoc, Achomawi, Northern Paiute, Wintun, Maidu, Pomo, Costanoans, Yokuts, Tubatulabal, Luiseno, Diegueno, and Colorado river tribes. For river crossing, a bundle or group of bundles of tules sufficed. On large lakes and bays well-shaped vessels, with pointed and elevated prow and raised sides, were often navigated with paddles. The balsa does not appear to have been in use north of California, but it was known in Mexico, and probably has a continuous distribution, except for gaps due to negative environment, into South America.

The balsa was most often poled; but in the deep waters of San Francisco bay the Costanoans propelled it with the same double-bladed paddle that was used with the canoe of the coast and archipelago of southern California, whence the less skilful northerners may be assumed to have derived the implement. The double paddle is extremely rare in America; like the "Mediterranean" type of arrow release, it appears to have been recorded only from the eastern Eskimo. The Pomo of Clear lake used a single paddle with short broad blade. The canoe paddle of the northwestern tribes is long, narrow, and heavy, having to serve both as pole and as oar; that of the Klamath and Modoc, whose lake waters were currentless, is of more normal shape. Whether or not the southerners employed the one-bladed paddle in addition to the double-ended one, does not seem to be known.

The occurrence of the double-bladed paddle militates against the supposition that the Chumash plank canoe might be of Oceanic origin. It would be strange if the boat minus the outrigger could be derived from the central Pacific, its paddle from the Arctic. Both look like local inventions.

Except for Drake’s reference to canoes among the Coast Miwok perhaps to be understood as balsas there is no evidence that any form of boat was in use on the ocean from the Golden Gate to Cape Mendocino. A few logs were occasionally lashed into a rude raft when seal or mussel rocks were to be visited.

A number of interior groups ferried goods, children, and perhaps even women across swollen streams in large baskets or in the south pots. Swimming men propelled and guarded the little vessels. This custom is established for the Yuki, Yokuts, and Mohave, and was no doubt participated in by other tribes.

Fishing

In fresh water and still bays, fish are more successfully taken by rude people with nets or weirs or poison than by line. Fish hooks are therefore employed only occasionally. This is the case in California. There was probably no group that was ignorant of the fish hook, but one hears little of its use. The one exception was on the southern coast, where deep water appears to have restricted the use of nets. The prevalent hook in this region was a single curved piece cut out of haliotis shell. Elsewhere the hook was in use chiefly for fishing in the larger lakes, and in the higher mountains where trout were taken. It consisted most commonly of a wooden shank with a pointed bone lashed backward on it at an angle of 45 degrees or less. Sometimes two such bones projected on opposite sides. The gorget, a straight bone sharpened on both ends and suspended from a string in its middle, is reported from the Modoc, but is likely to have had a wider distribution.

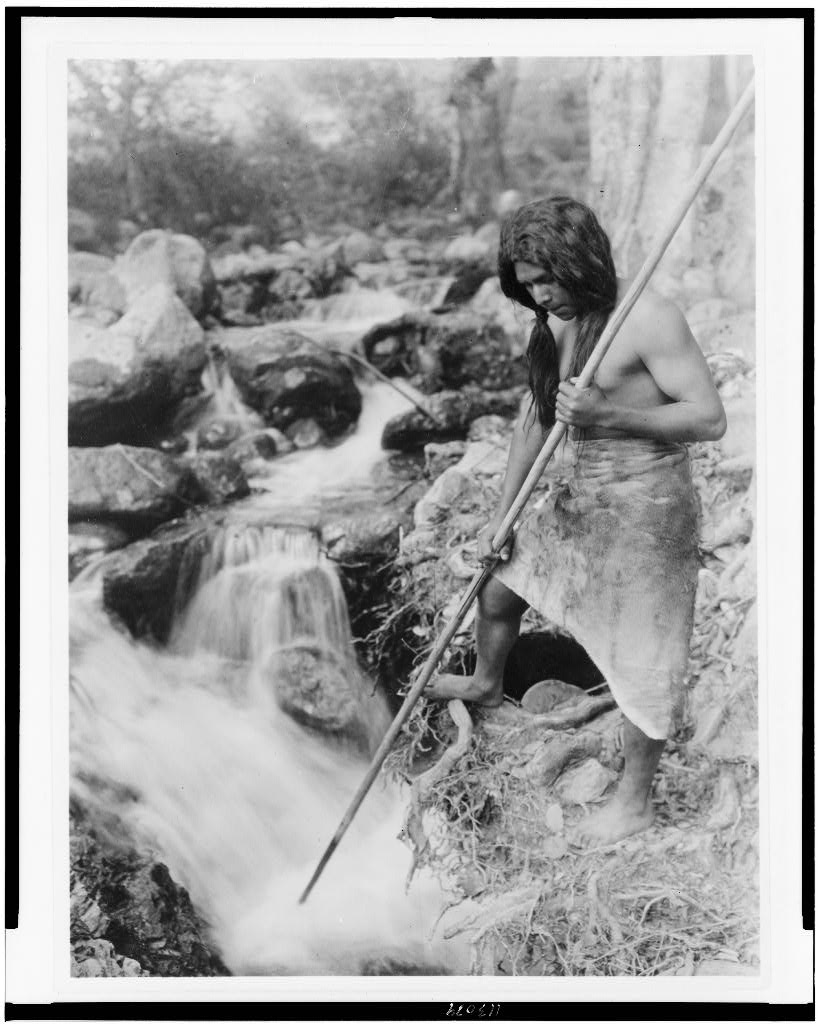

The harpoon was probably known to every group in California whose territory contained sufficient bodies of water. The Colorado river tribes provide the only exception: the stream is too murky for the harpoon. The type of implement is everywhere substantially identical. The shaft, being intended for thrusting and not throwing, is long and slender. The foreshaft is usually double, one prong being slightly longer than the other, presumably because the stroke is most commonly delivered at an angle to the bottom. The toggle heads are small, of bone and wood tightly wrapped with string and pitched. The socket is most frequently in or near the end. The string leaving the head at or near the middle, the socket end serves as a barb. This rather rude device is sufficient because the harpoon is rarely employed for game larger than a salmon. The lines are short and fastened to the spear.

A heavier harpoon which was perhaps hurled was used by the northwestern coast tribes for taking sea lions. Only the heads have been preserved. These are of bone or antler and possess a true barb as well as socket.

A single example of a Chumash sealing harpoon has been preserved. This has a detachable foreshaft of wood, set in a socket of the main shaft, and tipped with a non-detachable flint blade and a bone barb that is lashed and asphalted on immediately behind the blade.

There is one record of the spear thrower: also a specimen from the Chumash. This is of wood and is remarkable for its excessively short, broad, and unwieldy shape. It is probably authentic, but its entire uniqueness renders caution necessary in drawing inferences from this solitary example.

The seine for surrounding fish, the stretched gill net, and the dip net were known to all the Californians, although many groups had occasion to use only certain varieties. The form and size of the dip net of course differed according as it was used in large or small streams, in the surf or in standing waters. The two commonest forms of frame were a semicircular hoop bisected by the handle, and two long diverging poles crossed and braced in the angle.

A kite-shaped frame was sometimes employed for scooping. Nets without poles had floats of wood or tule stems. The sinkers were grooved or nicked stones, the commonest type of all being a flat beach pebble notched on opposite edges to prevent the string slipping. Perforated stones are known to have been used as net sinkers only in northwestern California and even there they occur by the side of the grooved variety. They are usually distinguishable without difficulty from the perforated stone of southern and central California which served as a digging stick weight, by the fact that their perforation is normally not in the middle. The northwesterners also availed themselves of naturally perforated stones.

Fish poison was fed into small streams and pools by a number of tribes: the Pomo, Yokuts, and Luiseno are specified, which indicates that the practice was widely spread. Buckeyes and soaproot (Chlorogalum) as well as other plants were employed.

Kroeber, A. L. Elements of Culture in Native California, University of California Press, 1922.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.