Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Jiu-jitsu Combat Tricks by H. Irving Hancock, 1904.

It is difficult for the skilled boxer of the Anglo-Saxon race to realise that his painstakingly acquired art is of no avail against the adept in jiu-jitsu. Yet the sooner this is realised to be a fact the sooner we shall cease reading in the newspapers of occasional instances where big Caucasians have tried pugilism on small Japanese, and have gone down ingloriously in the effort.

At least two or three times in every year we read of some Japanese who has had an altercation with an American policeman and has promptly put the latter on his back. Reinforcements, and still more reinforcements were called for before the Japanese was subdued and made a prisoner.

Last spring, in the Harvard gymnasium, there was an interesting encounter between Tyng, the strong man of that University, and a diminutive Japanese, a fellow student. Tyng tried his best foot-ball tackle, and threw his smaller opponent. But, after that, the Japanese eluded each effort to seize him. After the sport of dodging had continued for some time the Japanese darted in, took a lightning hold, and put Mr. Tyng upon the floor.

In Japanese ports a solitary native policeman has been known often to subdue as many as four turbulent sailors ashore from an American or English naval vessel, and to take the whole lot in submission to the police station. Indeed, the first American sailors to spend leave on shore in Japan after Perry had concluded the treaty with that country came home with the most wonderful tales. These sailors had had the not unusual lot to become involved in trouble ashore. They resorted to boxing with the natives. Upon their arrival here these same sailors declared that the country was peopled with devils whom the white man's best blows could not touch. Not only were these Japanese "devils" invulnerable to blows, but they actually picked up our men, one after another, and threw them into the sea!

Within the past year many exhibitions of jiu-jitsu have been given in the United States, and our younger athletes have had abundant opportunity to see jiu-jitsu and boxing contrasted. The result has been that these convinced athletes have started in promptly to acquire the Japanese art of meeting the boxer.

Seldom does the Japanese use his clenched fist. It is not considered "scientific." There is, of course, the legend of the Greek boxer who knew that he could deprive his adversary of his wind by a fist-blow in the abdomen, but who found that by driving the tips of his fingers against the abdomen he was able to penetrate deeply into the viscera. But the Japanese discovered, centuries ago, that the edge of the hand is not only more effective in warding off a blow, but that impact from such a blow will leave the adversary's muscles and bones aching. All of the common blows with the edge of the hand have been described in Chapter III.

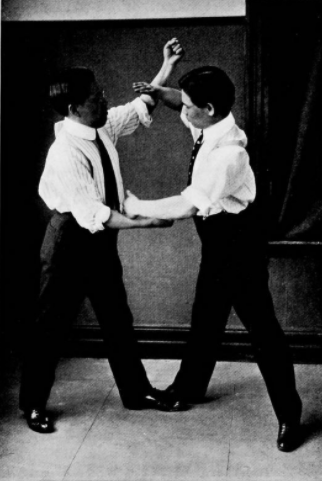

Photograph No. 11 shows a jiu-jitsian in the act of warding off a left-hander from his adversary. Here the man on the defensive has not struck with the edge of his hand, but with the edge of his fore-arm just back of the wrist. This is as it happens, it being impossible to gauge exactly in the swift movement of defence. But the blow with the edge of the fore-arm is scarcely less formidable than that with the edge of the hand. It will be noted that the assailant is met with a blow against the middle of his own fore-arm.

This method of defence meets all requirements. In the first place it is effective as a ward-off. In the next place the defensive blow on the assailant's arm results in soreness of that member for the boxer, and will weaken the force of any subsequent blow that he may aim with it. The edges of the jiu-jitsian's hand and fore-arm are so hardened by constant practice that he suffers no pain from the impact. Note, also, in the illustration that the man on the defensive has his left hand in readiness to guard himself against the boxer's right.

Very often the boxer follows up his left with his right so rapidly that the two fists seem to shoot out simultaneously. Even in this case the jiu-jitsian is not caught unawares. His hands fly to encounter the boxer's arms, and the latter, baffled in this quick attack, has also some pain to take up his attention. (See photograph No. 12.) At the same time the boxer is apt to be convinced of the futility of trying to reach such an opponent.

And this style of defensive work is most readily acquired. After a very few bouts of practice the jiu-jitsu novice finds that he is able, if he is as quick as the boxer, to stop any and all blows much more easily than he could if trained only in boxing. Much depends, of course, on the hardness of the edge of the hand, but the way to secure this has been ex- plained in Chapter III. It requires more time, however, to harden the edge of the hand properly than it does to learn defence with it.

A study of photograph No. 13 will result in a knowledge of how blows may be met by a defence close to the body. In this case the assailant is striking with a good deal of vigour, but the hand of the man on the defensive is forced to yield but little, and the blow is stopped.

At all times in practice, as in actual encounter, it is to be remembered that the jiu- jitsian, while warding off with one hand, is ever watchful and unceasingly ready to employ the edge of his other hand. This state of readiness does not call for one whit more of alertness or of agility in the jiu-jitsian than it does in the boxer. Any man who is quick enough to learn to box is quick enough to acquire the superior methods oi jiu-jitsu.

In one defensive blow the heel of the hand is used with effect. This is in parrying by striking the outer bend of the boxer's elbow. The blow is struck in a combination of forward and upward movement, and with a good deal of smartness. This ward-off, when employed after much practice, is very effective, for, besides defending, it shakes the boxer's confidence in his ability to land a blow.

And in at least one form the heel of the hand is used in an aggressive blow. At the first sight of an opportunity the jiu-jitsian strikes swiftly and forcibly upward, landing the heel of his hand under the point of his adversary's chin. It is not difficult to register this blow, and this feat of a second's duration usually is enough to wind up the bout or fight.

At close quarters, with a clinch at one side, but where one combatant has his hand free at the other side, the edge of the free hand is struck against the collar-bone at about its middle. Struck even lightly, this blow causes pain. When the blow is delivered with full force it results in a fractured collar-bone. A little practice, beginning with very light blows, increasing gradually in severity, will give the student a fair idea of how hard a blow of this sort may be struck without breaking the bone. And, in accordance with the well-known rule that use hardens, the collar-bone may be strengthened very considerably by undergoing endurable assaults upon it.

Blows with the tips of the fingers—jabs—are never to be delivered against any portion of the body except the abdomen and the solar plexus, A finger-tip blow against the ribs will leave soreness there, but the concussion is liable also to put the assailant's hand in bad shape.

When striking up the arm of an adversary by means of an edge-of-the-hand blow, the jiu-jitsian is advised to practise the trick of forcing up his opponent's arm higher and darting in under it to strike a blow of attack with the edge of his unoccupied hand.

The best defensive trick of all, of course, is one that stops the fight at the outset. The writer will now describe a trick that he saw performed in earnest, the defensive blow being struck with full force. The assailant struck out with his left fist. Quick as a flash the man on the defensive side-stepped once to his own left. In the same twinkling instant he let his right hand fly upward, the edge of the hand striking squarely across the assailant's right jugular, at a point midway between the jaw and the collar-bone.

A queer, gurgling sound came from the throat of the stricken one. His knees gave way under him, and he began to fall forward. Recovering, he succeeded in falling backward on his left hand and buttock. Less than half dazed, he was about to spring to his feet when his opponent's sharp warning came:

"Don't get up until I tell you to. If you do, you'll get hurt!"

The defeated assailant obeyed, sinking back to the sidewalk, while the man who had defended himself drawled:

"After this you would better not go around hunting for trouble until you've learned something about fighting. If you do, some day you will surely be hurt. Now, if you think you can go on and attend to your own affairs, you may get up and try it."

The assailant took the hint. So quickly and precisely had the defensive blow been given that it is doubtful if he understood just how his discomfiture had been brought about. And the best of it was that the man who had sought to provoke a fight had been stopped without sustaining any injury or disfigurement.

Hancock, H. Irving. Jiu-jitsu Combat Tricks: Japanese Feats of Attack and Defence in Personal Encounter, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.