Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Costume of the Ancients by Thomas Hope, 1812.

The defensive armour of the Greeks consisted of a helmet, breast-plate, greaves, and shield.

Of the helmet there were two principal sorts; that with an immoveable visor, projecting from it like a species of mask; and that with a moveable visor, sliding over it in the shape of a mere slip of metal.

The helmet with the immoveable visor, when thrown back so as to uncover the face, necessarily left a great vacuum between its own crown and the skull of the wearer, and generally had, in order to protect the cheeks, two leather flaps, which, when not used, were tucked up inwards.

The helmet with the moveable visor, usually displayed for the same purpose a pair of concave metal plates, which were suspended from hinges, and when not wanted were turned up outwards. Frequently one or more horses manes cut square at the edges, rose from the back of the helmet, and sometimes two horns or two straight feathers issued from the sides. Quadriga;, sphinxes, griffins, seahorses, and other insignia, richly embossed, often covered the surface of these helmets.

The body was guarded by a breast-plate or cuirass; which seems sometimes to have been composed of two large pieces only, one for the back and the other for the breast, joined together at the sides ; and sometimes to have been formed of a number of smaller pieces, either in the form of long slips or of square plates, apparently fastened by means of studs on a leather doublet. The shoulders were protected by a separate piece, in the shape of a broad cape, of which the ends or points descended on the chest, and were fastened by means of strings or clasps to the breast-plate.

Generally, in Greek armour, this cuirass is cut round at the loins; sometimes however it follows the outline of the abdomen; and from it hang down one or more rows of straps of leather or of slips of metal, intended to protect the thighs.

The legs were guarded by means of greaves, rising very high above the knees, and probably of a very elastic texture, since, notwithstanding they appear very stiff, their opposite edges approach very near at the back of the calf, where they are retained by means of loops or clasps. Those greaves are frequently omitted, particularly in figures of a later date.

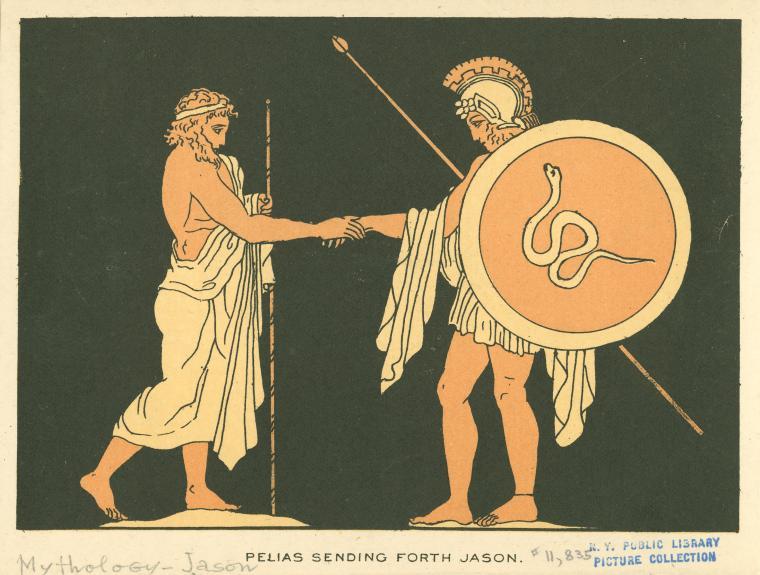

The most usual shield was very large and perfectly circular, with abroad flat rim, and the centre very much raised, like a deep dish turned upside down. The Theban shield, instead of being round, was oval, and had two notches cut in the sides, probably to pass the spear, or javelin through. All shields were furnished inside with loops, some intended to incircle the arm, and others, to be laid hold of by the hand. Emblems and devices were as common on ancient shields as on the bucklers of the crusaders. Sometimes, on fictile vases, we observe a species of apron or curtain suspended from the shield, by way of a screen or protection to the legs.

The chief offensive weapon of the Greeks was the sword. It was short and broad, and suspended from a belt, on the left side, or in front. Next in rank came the spear; long, thin, with a point at the nether end, with which to fix it in the ground; and of this species of weapon warriors generally carried a pair.

Hercules, Apollo, Diana, and Cupid, were represented with the bow and arrows. The use of these however remained not, in after-times, common among the Greeks, as it did among the Barbarians. Of the quivers some were calculated to contain both bow and arrows, others arrows only. Some were square, some round. Many had a cover to them to protect the arrows from dust and rain, and many appear lined with skins. They were slung across the back or sides by means of a belt passing over the right shoulder.

Independent of the arms for use, there was other armour of lighter and richer texture, wrought solely for processions and trophies; among the helmets belonging to this latter class some had highly finished metal masks attached to them.

The car of almost each Grecian deity was drawn by some peculiar kind of animal: that of Juno by peacocks, of Apollo by griffins, of Diana by stags, of Venus by swans or turtle doves, of Mercury by rams, of Minerva by owls, of Cybele by lions, of Bacchus by panthers, of Neptune by sea-horses.

In early times warriors among the Greeks made great use in battle of cars or chariots drawn by two horses, in which the hero fought standing, while his squire or attendant guided the horses. In after times these bigs, as well as the quadrigae drawn by four horses abreast, were chiefly reserved for journeys or chariot races.

The Gorgon's head with its round chaps, wide mouth and tongue drawn out, emblematic of the full moon, and regarded as an amulet or safe-guard against incantations and spells, is for that reason found not only on the formidable ægis of Jupiter and of Minerva, as well as on funerary-urns, and in tombs, but on the Greek shields and breast-plates, at the pole ends of their chriots, and in the most conspicuous parts of every other instrument of defence or protection to the living or the dead.

Of the Greek gallies, or ships of war, the prow was decorated with the cheniscus, frequently formed like the head and neck of an aquatic bird; and the poop with the aplustrum, shaped like a sort of honey-suckle. Two large eyes were generally represented near the prow, as if to enable the vessel, like a fish, to see its way through the waves.

Hope, Thomas. Costume of the Ancients, William Miller, 1812.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.