From My Quest of the Arab Horse, by Homer Davenport, 1909.

Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

[Homer Davenport was an Oregonian journalist and political cartoonist during the Gilded Age. Beyond his political activities, he was also one of the first breeders of Arabian horses in the United States. Through a connection with Theodore Roosevelt, he secured the necessary papers to travel to the Ottoman Empire and purchase Arabian horses as breeding stock. After visiting Constantinople, his party traveled to Aleppo, where he broke diplomatic custom by visiting a Bedouin dignitary before the city’s governor. This move led to him being gifted a desert mare, Wadduda, and secured him an invitation from the governor as well: the start of this excerpt. Later, Davenport would return with a few dozen Arabian horses, which remain the foundational stock of most American Arabian horses.]

At ten the next morning we went with Akmet Haffez to the Governor's residence. Nazim Pasha had promised to let us see the "Pride of the Desert," the great brown stallion presented to him by the Bedouins. I was glad to have that opportunity for Mr. Forbes had already told me of the horse as you will remember; but the heat was stifling, the reflection of the sun from the red and white sand was killing and I was anxious to get off to the Anezeh with Akmet Haffez.

Frankly I did not expect much of the "Pride of the Desert." I really resented the waste of time involved in this call on the Governor. Especially hard was it to go through the motions of drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes. I thought the time would never come when all the necessary eastern hospitalities would be over, but they came to an end at last and we were taken to a balcony of the palace to see the Governor's horses.

Right now I want to apologize. I had not known what I was to see or what I was to receive. It did not seem at all probable that the "Pride of the Desert" would amount to much—but when he was brought to the court yard I apologized to myself as I am doing to you now. We forgot all about heat and sun reflection. We could only think of the horse.

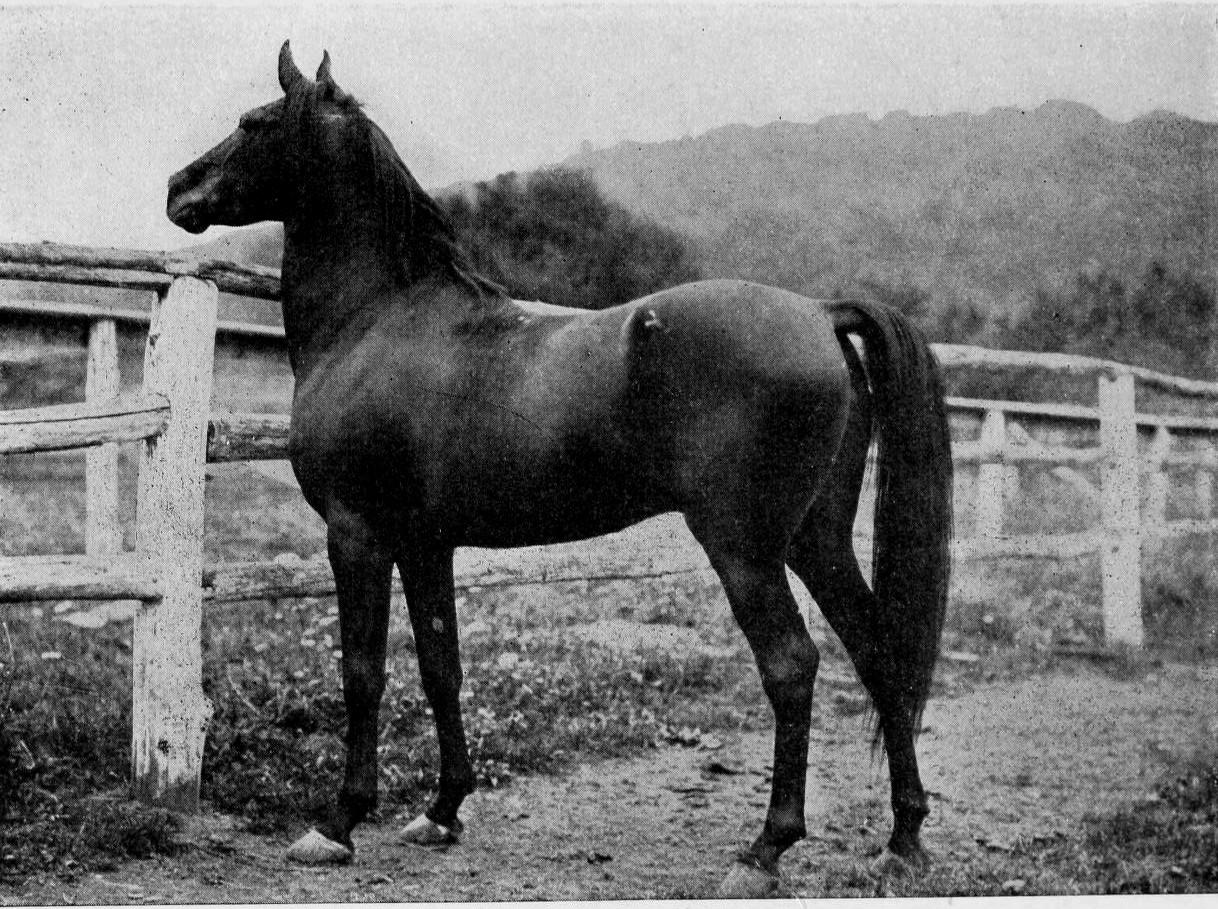

He was of the pure Maneghi Sbeyel strain and what a stocky fellow he was! He was powerful enough for any purpose, especially for a long killing race where weight was to be carried. There was not a white hair on him, and Akmet Haffez began on his fingers to count the stallion's pedigree through his dams' side, each one of which had been the greatest mare of her time. Other horses were shown, but we remembered only the brown stallion.

And here came the second surprise. Just as we were leaving the Governor's palace, he asked me to accept the brown stallion as his present. I had taken the war mare from Haffez, he said, and so I should accept this horse from him. This seemed to be beyond reason. The Governor was a poor man, and we had heard of the failure of the Italian Government to secure the horse, although a large price had been offered for him. But the Governor was firm.

"You have accepted," said he, "the present of the war mare, Wadduda, from Akmet Haffez; you must accept this horse as a present from me."

So I did, but later in the day I sent to Hickmut Bey, the Governor's son, as a present, a check for one hundred French pounds. Honors were therefore easy, but nevertheless I had had presented to me on the eve of my start for the desert, a mare and a stallion which I could not have purchased with all my letters of credit.

The rest of the day was taken up in preparing for the journey to the desert with Haffez. At five o'clock we had left Aleppo. I rode Wadduda; Haffez was on a bay, four years old, a Hamdani Simri; Thompson contented himself with his gray, and Moore straddled an Abeyeh Sherrakieh mare. One of Haffez's sons rode the "Pride of the Desert." A priest was sent as a secretary, and Ameene, of course, accompanied us.

The Governor had picked twelve soldiers to go as a guard, but I suggested that there was no reason for a guard when Akmet Haffez was with us; his presence was more than an army. The suggestion made an instant hit and when I asked the reason Haffez explained that the Bedouins had a poor opinion of such Europeans as they had seen because they always came to the desert surrounded by soldiers. The Bedouins believed that all Europeans were cowards. So, save for the rifle which I was carrying to present to Hashem Bey, we were without arms. Several camels with tents and provisions, had gone on with cooks and extra camel men.

It was a gala occasion. Akmet Haffez had not been outside of Aleppo for thirty years and, as he rode by my side, like a fine old Indian chief, his followers who lined the streets, were full of enthusiasm. It was a great evening. Still one thing bothered me. I had not yet made friends with my mare. She fretted and was nervous. I was on her back without the flowing robes usually worn by the riders she was used to. Jack and Arthur had donned Arab costume, but at the last moment I could not give up my flannel shirt and my comfortable ragged coat and trousers. So I broke the rules of the desert and went as I was dressed.

I argued to myself that some time Wadduda would have to get used to me and my clothes and that she had best begin at once. So I let her fret. We rode on for miles over dirt and rock and Wadduda still seemed fretful. She wanted something; that was evident, but what it was I could not quite make out. Then suddenly I was enlightened.

Just as the big red sun was setting we came to the desert. Wadduda stopped as if she were paying some tribute to the closing day. The faint roadway now seemed to disappear and before us was a vast barren plain. The sky was of a soft blue, tinted to gold by the sun, which had just set. I turned in my Oregon-made saddle, as easily as I could, that I might see where the rest of the caravan was. The mare did not notice my turning. With a quick and graceful toss of the head, she began to play. I sat deep down in my saddle and let her frolic uninterrupted. She finally stopped short, and snorted twice.

Turning slightly to the left she started galloping with a delightful spring. It was the return home, the call of the wild life with its thrills of wars and races; with its beautiful open air, as compared with the musty stuffed corral she had been picketed in. She was getting away from civilization and back to the open. Once in a while she stopped short, apparently to scent the rapidly cooling atmosphere. Now and then she pranced, picking her way between camel thistles. Her ears were alert; her eyes were blazing with an expression of intense satisfaction.

All this time, I found by my wet cheeks, that I had been crying with- out knowing it. I was wrought up to a state of much excitement. I was again a boy and felt the presence of my parents, and recalled the stories of the Arab horses, they used to tell me when I was a child. I remembered the drawings I had made of them as a boy. It was hard to realize that I was I, and that I was astride the most distinguished mare of the desert. I seemed then to realize what she was and what she meant to me. My face was dripping again and I felt glad I was alone.

Wadduda had stopped short again and was scanning the horizon. I touched the mare with my heels, but she did not move. She was thinking. Of what, who knows? Perhaps of her wars; or of combats on the desert, or of the keen edge of the Bedouin lance given when she had seen both horse and rider fall from the thrust of the spear of the Great Sheikh who had ridden her.

So for a long time we waited together — the mare and I, in the gathering dusk, and as we waited I almost wished that we could always be alone. The call of the desert came strong to both of us then.

But we were not to be left alone for long. The mare and I had ridden far in advance of the caravan, but now the people were galloping along in an effort to catch up. They soon reached us and Akmet Haffez, who would not let me go astray in the desert, took his place on my left, and so we rode and talked on and on into the beautiful night. I was tired from the excitement of the secret which only Wadduda and I knew and it was a relief to have Moore and Thompson tell me something that rested me. We were going to stop about midnight at the camp of a cousin of Akmet Haffez. We were to have a midnight dinner and start before sun-up toward the Anezeh.

But it was after midnight when we came to the singing and joyous Bedouins, who were shouting "Akmet Haffez!" "Akmet Haffez!" as we dismounted rather stiffly.

I helped take the saddle off my mare, and then we were ushered into a tall, cone-shaped mud house and escorted to a divan where the quilts and rugs were thicker. Before us, face down, on the clean, beautiful quilts, was the cousin of Akmet Haffez. He was mumbling a prayer and our interpreter softly translated it. The prayer was a beautiful sentiment. The petitioner was asking God to release him ever after from work so that he might stand at the caravan routes and tell all generations of the great honor that had been paid to him by us who were going to eat his rice and melons and who were to distinguish him further by sleeping under his shelter. It is true that the prayer was more eloquently thankful than most hosts would indulge in for a party so big and so hungry, but at the close of it we were led out into the yard where all his cattle and goats and sheep were resting and the sight of them made us more cheerful. Then we were taken into the cone-shaped mud house and there was a feast, long to be remembered.

It was spread on low tables about a foot from the ground, with short-legged little wicker stools for us to sit on. On the tables was spread bread about an eighth of an inch thick and this served as a table cloth. The bread baked on rocks in the sun, was made of barley and wheat rolled, and now and then in eating it you came to a full stop; a period as it were, consisting of a small gravel. In the center of the table was a large mound of finely-cooked rice and on top of this mound was a roasted head of sheep. The carcass, nicely roasted, was strewn around the mound of rice at intervals. There were red, yellow and green melons; egg plant, chicken cut up fine, and clabber milk of the goat, sheep, camels and cows. There were grape leaves rolled with rice in the center and there were fine light green grapes and fresh figs. To drink there was a mixture of sour milk and water.

When we sat down, I saw Akmet Haffez rolling up his sleeves. I saw no plates, knives or forks, or even spoons, but I took the hint quicker than Jack or Arthur. Possibly I had always lived nearer to the ground than they. Akmet Haffez had no sooner plunged into the rice than I did the same. His motions were easy to imitate, still the Bedouins laughed heartily at the quick way I mastered their simple art of eating. We ripped and tore at the table cloth and at the other dishes for more than an hour, and then having washed our hands out of a peculiar brass pitcher, we returned to our sleeping rooms. The program was to lie down and sleep till about three o'clock, when we were to start again and ride, reaching the Anezeh, we hoped, before it got very hot. At three o'clock we were saddling the horses and were soon off.

A couple of hours after sun-up, we began to realize that we were really in the desert. Two Arabs on mares, a gray and bay, came galloping toward us. They were carrying spears that looked fifty feet long. As they approached Haffez, they stopped and said "Salam Alakum — "Peace be with you." They talked for some minutes, when Ameene told me that some of the Anezeh had gone across the Euphrates to war, but that Hashem Bey had left his cousin a few miles on where the latter would receive us. We were disappointed that we were not to meet Hashem at once, but there was really no room for complaint, and with the couriers with the long spears we went on.

It was about eleven o'clock when we reached the top of a small knoll. I was sore and tired for I had not ridden for so long in years and the heat must have been telling somehow on my expression, for Akmet Haffez yelled to me to cheer up and pointing on ahead shouted: "Anezeh!" I looked, but could see nothing.

After a while, through the haze I noticed that the plain was covered with blackish tents and camels. And then the whole plain seemed to be covered with camels. In the distance they looked like row after row of tea-kettles. Wadduda was prancing. She had seen her tribe first. Tired as I was, it was a thrilling sight. It was the realization, at last, of a wish that I had cherished since a small boy, and my emotions got the best of me. We could see horsemen racing here and there. They were preparing to greet us and were getting into holiday garb.

Frankly it was too much for me. I tried to tell Akmet Haffez through the interpreter what I felt and to thank him for what he had done, but I am afraid I made a mess of it. That kindly old man saw my emotion and replied with all the native courtesy of the desert combined with the manner of the true gentleman. It was an honor to him, he said, that we had allowed him to introduce us to his Anezeh.

We were now getting near to the outskirts of the camp, and though I was as sore as an Aleppo button looks, under the excitement I urged on. We saw a big grass plot in front of a large tent. Haffez rode straight for it on his mare and as he dismounted, men came out and kissed him on the cheeks. All of the big officials had done this when an Arab took my mare and I got off. I could hardly walk and the heat was making me dizzy. I tried to be unconcerned, but my hips and knees were about broken.

Sheikh after sheikh we met, and we bowed and touched our right hands to our lips and foreheads as they did, and then shook hands. We were led in under a big reception tent. The bridle from my mare was brought in and tied to the center pole of the tent, denoting that we were welcome. We were at last among the Fedaan Anezeh, the most warlike and most uncivilized race of Bedouins in the world. To be frank again, I was much overcome with emotion to realize that we were in the tents of the greatest war tribe of Bedouins and under possibly the most favorable conditions possible.

Ameene felt that it was up to me to say something. Too tired to stand, almost too weak to talk from the heat, hunger and thirst, still I leaned toward the interpreter, and asked him to tell Akmet Haffez and the Anezeh, that while I had been born in the far western part of what he called "Americ," I had realized, ever since a small boy, that I was just as much of an Arab as any in the desert and that now that I had seen the Anezeh tribe, I felt I had been one of its members all my life. I thanked Akmet Haffez for bringing me to such a people, for it was the supreme moment of my life.

Without hesitation, this old man reached across the camel's saddle and with a voice full of emotion said:

"No, the day is ours, not yours; ever since the Anezeh became a tribe we have known that one of us was missing. Now you have come and the number is complete. To-day we celebrate the gathering of the entire tribe."

And thus was I received by the Anezeh.

Davenport, Homer. My Quest of the Arab Horse. B.W. Dodge & Co., 1909.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.