Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From The Book of the National Parks, by Robert Sterling Yard, 1919

The Spaniards found our semiarid southwest dotted thinly with the pueblos and its canyons hung with the cliff-dwellings of a large and fairly prosperous population of peace-loving Indians, who hunted the deer and the antelope, fished the rivers, and dry-farmed the mesas and valleys. Not so advanced in the arts of civilization as the people of the Mesa Verde, in Colorado, nevertheless their sense of form was patent in their architecture, and their family life, government, and religion were highly organized. They were worshippers of the sun. Each pueblo and outlying village was a political unit.

Let us first consider those national monuments which touch intimately the Spanish occupation.

Gran Quivira National Monument

Eighty miles southeast of Albuquerque, in the hollow of towering desert ranges, lies the arid country which Indian tradition calls the Accursed Lakes. Here, at the points of a large triangle, sprawl the ruins of three once flourishing pueblo cities, Abo, Cuaray, and Tabirá. Once, says tradition, streams flowed into lakes inhabited by great fish, and the valleys bloomed; it was an unfaithful wife who brought down the curse of God.

When the Spaniards came these cities were at the flood-tide of prosperity. Their combined population was large. Tabirá was chosen as the site of the mission whose priests should trudge the long desert trails and minister to all.

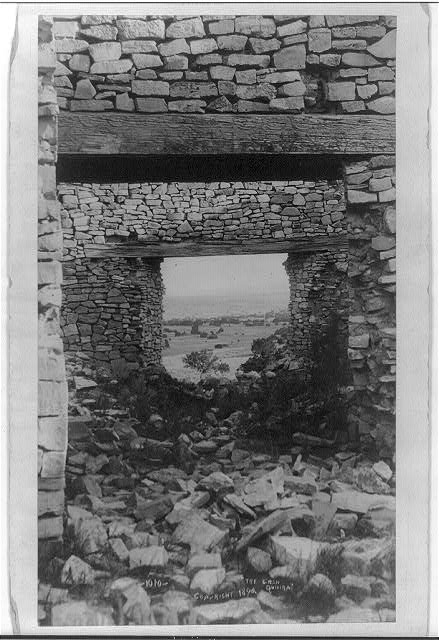

Undoubtedly, it was one of the most important of the early Spanish missions. The greater of the two churches was built of limestone, its outer walls six feet thick. It was a hundred and forty feet long and forty-eight feet wide. The present height of the walls is twenty-five feet.

The ancient community building adjoining the church, the main pueblo of Tabiri, has the outlines which are common to the prehistoric pueblos of the entire southwest and persist in general features in modern Indian architecture. The rooms are twelve to fifteen feet square, with ceilings eight or ten feet high. Doors connect the rooms, and the stories, of which there are three, are connected by ladders through trap-doors. It probably held a population of fifteen hundred. The pueblo has well stood the rack of time; the lesser buildings outside it have been reduced to mounds.

The people who built and inhabited these cities of the Accursed Lakes were of the now extinct Firo stock. The towns were discovered in 1581 by Francisco Banchez de Chamuscado. The first priest assigned to the field was Fray Francisco de San Miguel, this in 1598. The mission of Tabirá was founded by Francisco de Acevedo about 1628. The smaller church was built then; the great church was built in 1644, but was never fully finished. Between 1670 and 1675 all three native cities and their Spanish churches were wiped out by Apaches.

Charles F. Lummis, from whom some of these historical facts are quoted, has been at great pains to trace the wanderings of the Quivira myth. Bandelier mentions an ancient New Mexican Indian called Tio Juan Largo, who told a Spanish explorer about the middle of the eighteenth century that Quivira was Tabirá. Otherwise history is silent concerning the process by which the myth finally settled upon that historic city, far indeed from its authentic home in what now is Kansas. The fact stands, however, that as late as the latter half of the eighteenth century the name Tabirá appeared on the official map of New Mexico. When and how this name was lost and the famous ruined city with its Spanish churches accepted as Gran Quivira perhaps never will be definitely known.

“Mid-ocean is not more lonesome than the plains, nor night so gloomy as that dumb sunlight," wrote Lummis in 1893, approaching the Gran Quivira across the desert. “The brown grass is knee-deep, and even this shock gives a surprise in this hoof-obliterated land. The bands of antelope that drift, like cloud shadows, across the dun landscape suggest less of life than of the supernatural. The spell of the plains is a wondrous thing. At first it fascinates. Then it bewilders. At last it crushes. It is intangible but resistless; stronger than hope, reason, will—stronger than humanity. When one cannot otherwise escape the plains, one takes refuge in madness"

This is the setting of the "ghost city" of "ashen hues” that "wraith in pallid stone,” the Gran Quivira.

El Morro National Monument

Due west from Albuquerque, New Mexico, not far from the Arizona boundary, El Morro National Monument conserves a mesa end of striking beauty upon whose cliffs are graven many inscriptions cut in passing by the Spanish and American explorers of more than two centuries. It is a historical record of unique value, the only extant memoranda of several expeditions, an invaluable detail in the history of many. It has helped trace obscure courses and has established important departures. To the tourist it brings home, as nothing else can, the realization of these grim romances of other days.

El Morro, the castle, is also called Inscription Rock. West of its steepled front, in the angle of a sharp bend in the mesa, is a large partly enclosed natural chamber, a refuge in storm. A spring here betrays the reason for El Morro's popularity among the explorers of a semidesert region. The old Zuñi trail bent from its course to touch this spring. Inscriptions are also found near the spring and on the outer side of the mesa facing the Zuñi Road.

For those acquainted with the story of Spanish exploration this national monument will have unique interest. To all it imparts a fascinating sense of the romance of those early days with which the large body of Americans have yet to become familiar. The popular story of this romantic period of American history, its poetry and its fiction remain to be written.

The oldest inscription is dated February 18, 1526. The name of Juan de Oñate, later founder of Santa Fe, is there under date of 1606, the year of his visit to the mouth of the Colorado River. One of the latest Spanish inscriptions is that of Don Diego de Vargas, who in 1692 reconquered the Indians who rebelled against Spanish authority in 1680.

The reservation also includes several important community houses of great antiquity one of which perches safely upon the very top of El Morro rock.

Casa Grande National Monument

In the far south of Arizona not many miles north of the boundary of Sonora, there stands, near the Gila River, the noble ruin which the Spaniards call Casa Grande, or Great House. It was a building of large size situated in a compound of outlying buildings enclosed in a rectangular wall; no less than three other similar compounds and four detached clan houses once stood in the near neighborhood. Evidently, in prehistoric days, this was an important centre of population; remains of an irrigation system are still visible.

The builders of these prosperous conununal dwellings were probably Pima Indians. The Indians living in the neighborhood to-day have traditions indicated by their own names for the Casa Grande, the Old House of the Chief and the Old House of Chief Morning Green. “The Pima word for green and blue is the same,” Doctor Fewkes writes me. "Russell translates the old chief's name Morning Blue, which is the same as my Morning Green. I have no doubt Morning Glow is also correct, no doubt nearer the Indian idea which refers to sun-god. This chief was the son of the Sun by a maid, as was also Tcuhu-Montezuma, a sun-god who, legends say, built Casa Grande.”

Whatever its origin, the community was already in ruins when the Spaniards first found it. Kino identified it as the ruin which Fray Marcos saw in 1539 and called Chichillticalli, and which Coronado passed in 1540. The early Spanish historians believed it an ancestral settlement of the Aztecs.

Its formal discovery followed a century and a half later. Domingo Jironza Petriz de Cruzate, governor of Sonora, had directed his nephew, Lieutenant Juan Mateo Mange, to conduct a group of missionaries into the desert, where Mange heard rumors from the natives of a fine group of ruins on the banks of a river which flowed west. He reported this to Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, the fearless and famous Jesuit missionary among the Indians from 1687 to 1711; in November, 1694, Kino searched for the ruins, found them, and said mass within the walls of the Casa Grande.

This splendid ruin is built of a natural concrete called culeche. The external walls are rough, but are smoothly plastered within, showing the marks of human hands. Two pairs of small holes in the walls opposite others in the central room have occasioned much speculation. Two look east and west; the others also on opposite walls, look north and south. Some persons conjecture that observations were made through them of the solstices, and perhaps of some star, to establish the seasons for these primitive people. “The foundation for this unwarranted hypothesis,” Doctor Fewkes writes, ''is probably a statement in a manuscript by Father Font in 1775, that the 'Prince 'chief' of Casa Grande, looked through openings in the east and west walls 'on the sun as it rose and set, to salute it' The openings should not be confused with smaller holes made in the walls for placing iron rods to support the walls by contractors when the ruin was repaired."

Tumacacori National Monument

One of the best-preserved ruins of one of the finest missions which Spanish priests established in the desert of the extreme south of Arizona is protected under the name of the Tumacacori National Monument. It is fifty-seven miles south of Tucson, near the Mexican border. The outlying country probably possessed a large native population.

The ruins are most impressive, consisting of the walls and tower of an old church building, the walls of a mortuary chapel at the north end of the church, and a surrounding court with adobe walls six feet high. These, like all the Spanish missions, were built by Indian converts under the direction of priests, for the Spanish invaders performed no manual labor. The walls of the church are six feet thick and plastered. within. The belfry and the altar-dome are of burned brick, the only example of brick construction among the early Spanish missions. There is a fine arched doorway.

For many reasons, this splendid church is well worth a visit It was founded and built about 1688 by Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, and was known as the Mission San Cayetano de Tumacacori. About 1769 the Franciscans assumed charge, and repaired and elaborated the structure. They maintained it for about sixty years, until the Apache Indians laid siege and finally captured it, driving out the priests and dispersing the Papagos. About 1850 it was found by Americans in its present condition.

Navajo National Monument

The boundary-line which divides Utah from Arizona divides the most gorgeous expression of the great American desert region. From the Mesa Verde National Park on the east to Zion National Monument on the west, from the Natural Bridges on the north to the Grand Canyon and the Painted Desert on the south, the country glows with golden sands and crimson mesas, a wilderness of amazing and impossible contours and indescribable charm.

Within this region, in the extreme north of Arizona, lie the ruins of three neighboring pueblos. Richard Wetherill, who was one of the discoverers of the famous cliff-cities of the Mesa Verde, was one of the party which found the Kit Siel (Broken Pottery) ruin in 1894 within a long crescent-shaped cave in the side of a glowing red sandstone cliff; in 1908, upon information given by a Navajo Indian, John Wetherill, Professor Byron Cumming, and Nell Judd located Betatakin (Hillside House) ruin within a crescent-shaped cavity in the side of a small red canyon.

Twenty miles west of Betatakin is a small ruin known as Inscription House upon whose walls is a carved inscription supposed to have been made by Spanish explorers who visited them in 1661.

While these ruins show no features materially differing from those of hundreds of other more accessible pueblo ruins, they possess quite extraordinary beauty because of their romantic location in cliffs of striking color in a region of mysterious charm.

Yard, Robert Sterling, The Book of the National Parks, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1919.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.