“Festivals of the Church” from Russian Festivals and Costumes for Pageant and Dance by Louis Harvy Chalif, 1921.

The New Year

Following the old calendar of the "Orthodox" or "Greek" church, the Russian year begins on what is, here, January 14. Their "New Year's Eve" — January 13 — is, by the church calendar, St. Sylvester's Eve. This is a night of great possibilities, according to popular superstition; almost anything in the way of the supernatural might occur. In some districts the peasants cherish the belief that the miracle of the wedding feast of Cana may be repeated at stroke of midnight. So they fill large jars with water and sit around them waiting for the water to be converted into wine. There seems to be no authentic instance, however, of their hopes being realized.

Whether the girls who try, on this mystic eve, to pry into the future and learn what matrimonial fate awaits them are more often rewarded is uncertain, also. They have various formulas for the test. One consists of placing a wedding ring in a glass of clear water and gazing through it until the face of the lover-to-be appears to her. In another, the inquiring maiden shuts herself into her room with two mirrors which she places opposite so that each reflects the other. Then, putting a candle on each side, she seats herself between the mirrors, watching intently for the countenance of her future husband to appear in the rear glass, reflecting in the one she faces. Still another way is for the girl to go out alone into the highway at midnight to ask his name of the first man who passes by, believing that it will prove to be the name of the destined mate; but this test is probably not very popular with timid damsels, and still less so with their sensible and prudent mothers.

Having devoted the New Year's Eve to' questioning the fates and trying to look into the future, when the day comes all throw themselves into whole-hearted enjoyment of the present. Every "izba" is decked out for gayety and abundant refreshments provided for the boys and young men who go from door to door singing the New Year songs and throwing, as we do confetti, wheat, rice, corn and dried peas. These are a symbol of the prosperity and happiness all wish for each other to enjoy during the year to come. In return for the songs and good wishes, each family visited insists upon treating to varied delicacies, rich cakes and tempting drinks ; sometimes even gifts of money are offered.

Epiphany and the "Benediction of the Waters"

Should any maiden be still unsatisfied after her attempts to read fate on the old year's last night, she can try again on Epiphany Eve, January 18. A test belonging peculiarly to this eve is "throwing the shoe." The girl goes outside her own gate and standing with her back to it and her eyes closed, throws an old shoe. The way the shoe is found to lie reveals the direction from which the youth of her dreams and hopes is to be expected.

Water blessed by the priest at the Epiphany church service is firmly believed by the devout peasant to have great curative power. It is brought home in a bottle to be kept beneath the holy image or ikon in the place of honor or "krasni ugol" — "beautiful corner." A few drops of this water will be administered to the sick all through the rest of the year, or given for relief from fright, or to drive away any of the powers of darkness, were it the very "Old Nick" himself.

The next day, January 19, brings a very important date in the church calendar. There is no more imposing or impressive ceremonial observed in all Russia than that of the "Benediction of the Waters" or "Fete of the Jordan." In all cities and large towns situated upon streams, stately processions of vested clergy and worshippers together with the soldiers, move to the music of chanting choir and military band down to the river's bank where a cruciform break is made in the ice through which the cross borne in the procession is dipped into the water with the priest's blessing. At this, there is a military gun salute, followed by the sprinkling of the people in benediction by the priest.

In February

February has its day of religious festivity also: the “Purification of the Virgin" on the 15th. On that day youths and maidens go out very early in the morning, bearing willow wands with which they decorate one another, wreathing them about the waist and waving them in the dance or in the games which they enjoy until breakfast time, when all partake of an outdoor picnic.

"Mazlenitza"

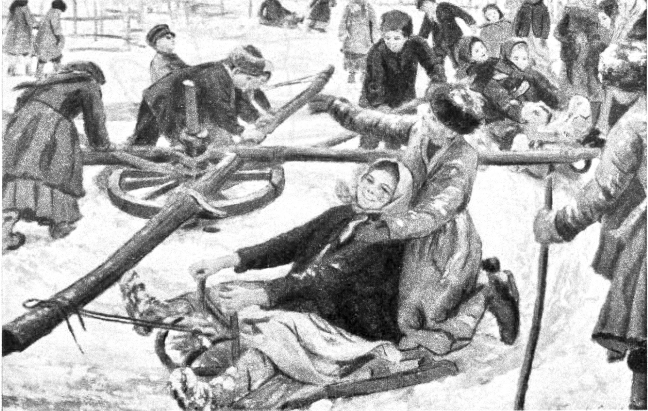

"Mazlenitza" or carnival week—the last before Lent—is called in Russia "Butter Week." The name is well justified by the tremendous amount of melted butter consumed upon the "bliny" or rye flour pancakes prepared after a special recipe and served hot with not only the butter but also with sour cream and caviar. In every Russian house-hold these "bliny" form a prominent, if not the chief, part of the family diet during "Butter Week." But this is not the week's only name. It is also called the "Broad" week, the "Honor" week, the "Happy" week; "the sister of thirty brothers and the daughter of three mothers"; "the grandchild of forty grandmothers"; "a paper body with a sugar mouth"; and other fantastic titles. Each of its days has also its name, as follows: Monday: Wstretsha, "the welcome." Tuesday: Zaigry, "the play-day." Wednesday: Lakomka, "sweet mouth." Thursday: Shiroky, "the broad." Friday: Matchikha, "the step-mother." Saturday: Zolovka, "sisters-in-law company." Sunday: Proshtshalny den, "farewell day." As in the Latin and Catholic countries, this is a great time for gayety. Dancing and feasting occupy the evenings; there is as much revelry as if the coming Lenten abstinence were going to last six years instead of weeks. But that is just the whole-hearted Russian way of doing things. The fasting and religious observances will be equally thorough.

Palm Sunday and Holy Week

When Palm Sunday comes, every one goes about bearing boughs of "pussy" willow. They take the place of the strips of palmetto distributed to American congregations, in a way, but have other significance as well. After being taken to the church and presented to the priest for blessing, they are carried to the fields and waved above the springing grain as a protection against damage by storm or hail. Some of the devout think that the blest buds or "pussies" have medicinal value, or at least have power as an antidote for sore throat, and swallow them for that purpose—a rather difficult feat, considering their fuzziness.

After these more serious uses of the willow, the boys play with the wands, doing frolicsome battle with them in which they say, "it is not I, but the willow, that beats you."

An odd superstition with some Russians is that any one who eats honey on Holy Thursday—the Thursday before Easter—need not fear being stung by serpents.

Besides the universal religious beliefs attached to Good Friday, the Russians have some quaint legends and superstitions of their own. One is that the day is an especially propitious time to seek buried treasure, if it is undertaken before sunrise. And that on this day one may gaze into the sun without being blinded.

But the most interesting is the tale of the spirit of "Good Friday," represented as a wrinkled old crone, going about spying upon the housewives to see if her day is being properly observed and inflicting dire punishment where she finds one at work. One legend has it that "Good Friday" once visited a woman who was busy at her kneading trough.

"What are you doing?" asked the gaunt and fearsome visitor.

"Don't you see.? I am kneading dough," impatiently the woman replied, not taking the time to look up from her work. "Good Friday" made no rejoinder, but turned and left the house. Straightway the over-industrious housewife's hands were changed to wood like her kneading bowl.

Easter

On Easter Eve—Holy Saturday—the churches are brilliantly illuminated and the choir's harmonious voices fill the air with rejoicing. The sacred building is thronged with worshippers awaiting the midnight mass and the supreme moment when the choir will burst forth in the triumphant "Christ is Risen," and the bells will peal the joyous hour. At this, each one will kiss his neighbor three times. In this greatest of the church's celebrations, the material side is not forgotten. The women stand about laden with plates and baskets of food, waiting for the priest to bless and sprinkle it with holy water. On the cakes and eggs thus blest, each household will "break the fast" of Lent before beginning the Easter feasting.

Easter Day, after its highly ornate church services, is observed as the supreme feast day and occasion of hospitality. In every home one or more large tables are decorated with flowers and little lambs made of butter, cheese or sugar, and set out with abundance of rich and appetizing foods and drinks of which each visitor is expected and urged to partake.

This is but the beginning of the three days spring festival, during which the whole village or neighborhood will unite in outdoor pleasures. All dressed in their gayest festal attire, they repair to the fields or meadows, there to dance and play games. Easter Monday has the most distinctive customs. On that day the favorite willow again appears, the boys ornamenting small wands with gay ribbons. They go about chasing the girls and trying to switch them with the wands "so they wont be lazy." When they succeed, the victim must buy off with a brightly colored egg. Easter eggs are also given as a reward for the carols sung by the youths as they go from house to house. Refreshments, too, are offered; home-made Easter cakes—kulicha and paska—and various drinks. Beautifully decorated eggs are considered appropriate gifts between lovers at this time.

St. George's Day

St. George's Day, though a church festival, shows every sign of being also a survival of the Pagan idea of drawing strength and beauty from contact with Mother Earth. This is a thought that seems peculiarly congenial to the Russian peasant mind. All through the year we see him using every occasion, whether it be a religious one or not, to celebrate this communion with nature. He uses, as we have seen, simple natural things as his symbols: willow wands, grass, flowers; and shows himself thus to be a child of Nature, full of childlike imagination and poetic instincts, craving beauty and ever striving to create it.

On the eve of this festival of St. George rural maidens often take water from the mill pond home with them for bathing, believing that strength and beauty come from such baths. On the day itself the first out-door bathing is indulged in as a sort of ceremonial, the men and boys going to the rivers or lakes, while the women splash in the small garden pools. Other methods of absorbing vigor and beauty from nature consist in rolling upon the new-sprung grain in the fields, or swinging upon the boughs of the dog-wood trees. One pretty custom is that of throwing flowers into the water churned into commotion by the mill-wheel as a sort of oblation or propitation of the stream so that no one may be drowned during the coming season.

Other Summer Festivals of the Church

On May 9, the name day of Little St. Nicholas—also called "the warm Nicholas" to distinguish his fete from that of the other, the "cold" Nicholas, on December 19—there is more merry-making in home and field. And again on the 14th the Russian peasant garlands his doorway with flowers and goes picnicking to the woods in honor of St. Jeremiah.

On Whitsunday—Pentecost—all the peasants come to church dressed in their light, gay-colored summer attire and bearing birch twigs and bouquets of flowers. There is a saying oft repeated by them that the person who brings no flowers to church on that day shall shed as many tears for his sins as the birch twig can hold of dew drops. This is another day upon which anxious girls may question fate on the all-important subject of future husbands. They throw garlands upon the stream, and if one sinks, its owner must face another year of single blessedness. The floating wreaths permit hope, and their course indicates the direction from which the lover may come.

On the following Sunday, Troyitza—Trinity—the high tide of joyous life and growth is celebrated. Flowers, birch boughs and grass are used in abundance to adorn the homes or izbas, being even strewn upon the floors.

St. John's Day, June 24, called here the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, is the propitious time for gathering herbs and flowers which are supposed to have medicinal properties. Doubtless some of them do—and at any rate there is another pleasant occasion for roaming the fields and forests, and, in the case of the boys and maidens, assisting fate in the business of pairing for the life- journey.

July 12, the name day of Sts. Peter and Paul, is everywhere observed, but in many places it is a very great occasion indeed, because of the great number of churches called by the names of these two mighty pillars of Christianity. In such villages or towns this will be the date of the 'Varmark" or yearly fair, with all its accompaniment of dancing, music, abundant eating and drinking and the exchanging of gifts such as cakes or other small tokens.

On August 1 comes the blessing of the horses by the priest, and this date is also the proper time, set apart by custom, for gathering honey.

The 2nd of this month is St. Elijah's day, but the poor saint has in some way become confused in the peasant mind with the Slavonic god of thunder, Perum, whose wrath devastates the land by storms and hurls bolts from heaven to terrify or smite trembling mortals.

August 19, the Transfiguration, brings the “blessing of the apples" and of the honey. In some villages situated in vine-growing districts this date is set apart for the priest to bless the grapes. Everywhere it is observed as a sort of fruit harvest and time of rejoicing, when the new fruit is eaten and all the usual forms of merry-making indulged in.

Saints' Days of Autumn

On September 27 a religious festival and service of thanksgiving for the gathered harvest is held. This is made an especial day for family reunion, much as the American Thanksgiving-Day is observed.

November 2, All Souls' Day, is devoted to tender remembrance and mourning. In Russian rural districts offerings of wheat and of honey are placed upon each grave and then offered to the passer-by with the solemn greeting, "May God forgive your sins."

November 26 is a church festival in honor of St. John the Zlatoust or "golden-mouthed," who composed the liturgy used daily in the Eastern Orthodox church. The "cold" St. Nicholas has his turn for remembrance on the 19th of December, when there is a church service at which his picture is kissed by the devout and lighted candles placed before his ikon, or holy image.

Christmas in Russia

The Russian Christmas falls on what would be January 7 according to the Western calendar. A volume could well be written about the many quaint and charming observances of this supreme feast and religious celebration in the peasant home and village. So great is its importance that preparations are going on long before the actual date arrives. The young men and boys of each village come together to practise singing the Christmas carols or "kolyada" and to prepare the huge and highly decorated gilt star which they are to bear at the head of the Christmas Eve procession from house to house. If it is a town or large village there may be two or even several groups of singers. In this case there is keen rivalry in the matter of their carols and especially as to the splendor of the star. This is sometimes six feet in diameter, gilt, of course, and has gay garlands and streamers floating from it, while the centre has some brightly colored religious picture with a place contrived to hold a lighted candle. Of course the Christian origin of this is the Star of Bethlehem, but confused with it seems to be some relic of the older religion and the worship of the sun. There is lavish use of gilt paper and tinsel in the house decoration, especially as to gate and door posts, and seemingly an idea of inviting the sun-god to bless their threshold with his benevolent rays. And in the old carols sung by these groups of youths a word is used in refrain, "ovsen," which is by some supposed to be a corruption of "iasen," a Russian name for the sun; others, again, think the word is derived from the word meaning "oats" and throw oats into the house while singing the carol.

But before the visit of the "kolyada" singers comes the breaking of the fast—for, unlike the western way, the day before Christmas is a fast for the Russian—in a long and ceremonial family meal. No meat must be eaten until the evening star is seen, therefore the important dish with which this meal is begun is a fish, called, whether it literally is, or no, a "pike." A regular ceremony is gone through with in the matter of this fish. It is brought home by the master of the house, who cries joyfully to the wife, "I’ve got the fish," "A pike.?" "A pike." "God be praised" is the wife's final response as she takes it to prepare it for eating.

There is a pleasant story of the great Catherine who once invited her famous general Suvoroff to partake of the Christmas Eve banquet with her. The Empress ordered that a very rich feast be spread, with dishes of unusual and ingenious composition. Now the General Suvoroff, as his sovereign well knew, was a very devout man, and would sooner taste poison than anything but fish before the rising of the Christmas evening star. So the great Catherine tempted him, wittily trying to persuade her guest that nothing but fish of different kinds and subtly seasoned, was set before him. All in vain—as no doubt the wise Empress had foreseen. So, calling a messenger and whispering her commands to him, she ceased her teasing until the courier returned, bearing, on a splendid platter, the diamond-studded star of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky. Smilingly taking the gorgeous decoration and presenting it to her amazed general, she said : "Now you have seen the Star; will you not eat?”

The festive feature of this meal is a sort of plum-pudding called the "koutia," and the platter upon which it rests is called the "pokoutia." The carrying of this to the place of honor reserved for it is regarded as a great distinction and privilege by the member of the family selected as bearer. There are certain mysterious rites observed also with regard to the "pokoutia," other symbolic objects being placed upon it besides the "koutia" — a wisp from the interior of a haystack and a honeycomb. This must be done with great care, as for anything to fall from the "pokoutia" would be a very serious omen. The bearer, before grasping the platter, must cross himself and bow three times towards the dish. In its final place of honor upon the evening feast table it is surrounded by lighted candles, which furnish the illumination for the banquet. There is a long and solemn religious ceremony at the table, led by the head of the house, who is, on this great occasion, regarded as an officiating priest. He dresses, if possible, in white and holds in his left hand a vase of ladon or incense which he waves about, censer-wise, at the beginning of the evening's religious ceremony. His place at the table is behind the candle-sur- rounded pokoutia.

If it is a large establishment with servants there will be two tables, but all will eat together, and in the ceremony followed each name is called in blessing, thus: "May my son, so and so, be happy. May my servant (calling his name) "be happy." Even the dead are mentioned with the wish "May they attain Paradise." The Russian being tender-hearted, simple, and full of emotion, the tears are apt to flow freely on this occasion, until the signal is given by the master of the house to drive away sadness and begin to rejoice.

An old superstition has it that the first sneeze at the Christmas evening table must be rewarded with the gift of a sheep or a calf. So the mischievous youngsters are wont to provide them- selves with sneezing powder and a great number of explosions occur as soon as the solemn part of the meal's ceremony is finished. But Father is not so easily taken in; perhaps he himself, as a boy, was up to tricks. The first of these fraudulent sneezers receives the gift of the family cat.

Probably the "kolyada" singers will arrive before the house at this juncture, and there will then be great hilarity. Treating the guests, giving presents and urging refreshments upon all, follow. There are masqueraders, too, in the guise of bears, donkeys and the like with, always, some one in the garb of "Diedushka Moroz" — Old Grandfather Frost. This personage much resembles the American "Santa Claus."

The Russian peasant is such a gregarious creature that a traveler who visited the country early in the nineteenth century said that where the English and the Germans enjoyed themselves in ''family" groups, the Russian was not happy, not ready to give himself up to whole-hearted enjoyment, until he had gathered together his whole neighborhood or "mire" to frolic with him.

This impulse sometimes leads whole Russian villages to plan their Christmas festivities together, agreeing upon one "izba"—of course a large one—in which to feast and to dance and sing. The family chosen to play hosts feel hugely honored, and at once set about notifying everybody and pressing all to come. If there is a betrothed girl in the family, the compliment is especially appreciated, and it is usually such a household which is thus honored.

In the past, feudal times, the great noble or land-owner was wont to entertain the whole district. A great tree was provided and dazzlingly adorned, while plentiful and delicious food and drinks of all kinds were pressed upon all, from the highest to the humblest alike. There is no place like Russia for insistence upon human brotherhood; even when government and laws were most cruel and oppressive, the actual personal relations between lord and serf were without haughtiness on the one hand or cringing on the other. Therefore, you may look to the Russian, of whatever station, for simple and sincere, unaffected good manners—a thing never too common, and greatly to be prized.

To return to the Christmas gatherings—if the guests came from some distance, they would drive up in gaily decorated sledges with bells ringing. A large family would fill several vehicles, and the greater the number, the more honor to the entertaining family. Arrived before the izba, one of the party, usually an elderly woman, must alight and go to notify the hostess of the coming of guests. The rest of the caravan sit outside until host and hostess come to urge them to enter. Once within, the eating and drinking begins; the drinks, especially, are urged upon the men, usually with success, though one who abstains is greatly respected.

The young people soon begin to dance. All the village musicians are there with their balalaiki, their sapelki, their harmonicas and tambourines. Wild, eccentric dances will be performed by the youths of the masquerading group who impersonate various animals, grotesque and legendary beings, and even the devil himself.

Do not suppose that one evening of such hilarity will satisfy our gayety-loving peasants; after a few hours of sleep the dancing and feasting begin anew and may continue for two or three days. The few days quiet that next ensues will restore them and prepare them to enjoy the coming New Year celebration.

The Ikon's Visit

Besides these regular and stated festivals of the church, other picturesque ceremonials take place from time to time. One is the bringing of some especially sacred ikon from its accustomed shrine in the cathedral or important church to the outlying villages. This is believed to bring untold blessings to the favored community, whose appreciation must be shown by substantial contributions to the church's funds. The holy image rides in state in a splendidly decorated sledge and is attended by priest and acolytes. This is a much grander occasion, of course, than the visitation, during Easter week, of the homes by the local ikon, in charge of the priest and borne by the boy choristers or assistants.

Secular Holidays

If you have noted the dates of the foregoing religious festivals you are aware that May is a very busy month. Yet there is also the important secular celebration of "Mayday"—Maiovka—on the first. The night before, April 30, is devoted to the ancient rite of "burning the witches." The old superstition has it that on this eve these spirits of evil try to enter the homes and work their wicked spells. So this must be prevented by laying upon each doorstep a cross-shaped pile of grass blades upon which sand is heaped. It is believed that the witches are unable to effect an entrance until they have counted every grass blade and every grain of sand. You can see that the poor witch has a very small chance to accomplish anything under such circumstances.

And as if this precaution were not enough, the boys take great delight in building huge bonfires upon the hilltops where the evil ones are supposed to be burnt. All the youths and boys of the neighborhood assemble here and leap about, singing and shouting and often "showing off" by jumping through the leaping blaze, thus defying the witches and proving their courage. The youngsters also play with torches made of brooms dipped in tar and fired. These they wave aloft with such terrifying effect that surely any witch who may have escaped the bonfire will fly as far from that region as her own broomstick will carry her.

On this eve, also, the maypole is erected before the dwelling of the village maiden who has been voted the most popular. It is a great day for lovers. The appropriate gift from a swain to his chosen sweetheart is a small tree adorned with bright ribbons and hung with colored eggs. These decorated eggs seem to be used at all seasons, and are not alone an Easter and Christian symbol as it is here, but are connected with ancient superstition and the worship of the "new sun," the Pagan emblem of growth and fertility. For this reason the use of colored eggs is under the church's ban in Russian Poland.

After the lovers have exchanged their tokens and the gay maypole has been sufficiently admired, all go together to the fields and spend the day in picnicking, with dancing and merry songs.

Ivan Kupala

July 7 is called "The Day of Ivan Kupala," but exactly who this legendary personage, whose "day" is sometimes confused with that of St. John, may be, we are unable to say. But he must have been a gentleman of some importance as all kinds of strange happenings may be expected upon his "eve." This is the time to watch for the blossoming of a certain flower which blooms but once a year and brings all manner of good luck to the one fortunate enough to behold the exact moment of unfolding. On this eve hidden treasures are to be found and he—more likely, she—who will gather twelve different kinds of herbs and sleep upon them shall have the future revealed to him. This occasion corresponds, in folk-lore and superstition, to the English "Midsummer Night" so poetically and humorously dealt with by Shakespeare in his "Midsummer Night's Dream."

Haymaking

For the student of pageantry, no occasion would afford much more interest than the Russian haymaking festivities, with the village's favorite maiden crowned as queen, the whole gay band, armed with wreaths and wands, forming a parade to escort her back to her "izba" at even, with a pause at the church on their way, to offer a prayer. Nor, for all their hearty labor and equally vigorous play, are they too tired to dance at night until another day has almost come.

The "Yarmark"

The yearly fair, or "yarmark" also offers many picturesque and characteristic scenes. Usually the fair is held upon the name day of the village church's patron saint, and sometimes lasts for days, according to the importance of the place as a market. Gala costumes come out of their chests for this important occasion, the musicians spend all their time playing for the untiring dancers, and an onlooker would say that everything but trading was going on in the noisy, gay assembly. But that is the Russian way; he makes up his mind silently and transacts his business at last most efficiently without having seemed to interrupt the really important occupation of merrymaking. Another very important line of activity is carried on at the fair: it is the great time for match-making. Many a stalwart young peasant who has disposed of his crop of grain or his year's trapping of furs to advantage, then looks about him for a help-mate and not in vain, for the pretty, wholesome peasant girls are usually inclined to matrimony, being children of nature, and looking forward, from their cradles, to home-making and motherhood as their proper destiny.

Chalif, Louis Harvy, Russian Festivals and Costumes for Pageant and Dance, Chalif Russian School of Dancing, 1921.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.