Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

Letter No. 2

Winnipeg,

April 16, 1911.

My Dear Mother,

At last I am in the capital of the great “West,” and am nearly at the end of my travels. I am not sorry, for the railway journey is far more disagreeable than the sea voyage, except those three first days; and I was very sorry for the poor women, who had a lot of little children to look after on the train. The first-class people had beautiful railway carriages, with a dining car and sleeping berths, and I daresay were almost as comfortable as if they were in a good hotel; but we second-classes could not expect that, and we did not get it. There was no real hardship, only it was uncomfortable and tiring.

At Montreal I bought a basket of food to last till we reached Winnipeg. I paid six shillings for it. It contained bread, butter, jam, canned beef, cake, tea and sugar; and was enough, for I was not nearly so hungry on the train. The "cars" were rather crowded, and the intermediates and English steerage all came the same class. The Galicians, or whatever they were, were put in two carriages by themselves, fortunately for us. The sleeping accommodation was rough, bare berths were fixed up, each for two, but there were no mattresses, and some of the fellows had brought no blankets of any kind, and with the hardness of the berth and the jolting of the train, were pretty stiff and chilly in the morning. I was very glad of the two heavy rugs that I had with me.

As I was in a lower berth, and could see out of the window, I saw a good deal of the country we passed in the night, for there was a full moon, and I woke up a great many times. I must describe the journey as shortly as I can, for I want to tell you most about Winnipeg. The whole journey seems only to have left four or five distinct impressions on my mind, in something like this order: first, a long stretch of country, not so very unlike home, farm-houses, trees and orchards, ploughed fields and meadows, with every few miles a country village, then followed a long run through a hilly, rocky country with fir or pine woods, and for a good distance a wide river not far from the railway.

The river, I think it was the Ottawa, was very beautiful, with its high banks covered with evergreen trees, while floating down it were huge rafts of logs, with little huts on them, or tents, and men to pilot them along.

At last we came in sight of some part of Lake Superior. We would run for quite a long way in full sight of the lake, with its waters shining in the sun with here and there little rocky islands, and then we would be back in the forests again. It was beautiful, but there was such a lot of it, and it was so lonely and lifeless not a bird or beast to be seen. The last stretch of our journey was in the night, but by the moonlight it still seemed to be rocks and mountains, forest and lake, till we got nearly to Winnipeg, when we came into a flat country, with openings in the woods and occasional farm-houses. We got into Winnipeg at about 9 o'clock this morning, and the first thing Jack Dalton (that's the fellow who was with me at Quebec) and I did was to go to a restaurant, where we got a good breakfast for a shilling.

We then went down to the Emigration Office near the station, to try and find out where we had better go to look for farm work. We found most of our fellow train passengers there pretty thick on the ground too. Emigrants who wish can stay there for nothing till they go out to the country places, and there are berths for them to sleep in, and stoves and things for them to prepare their own food. Jack and I decided, however, that if we had to stay a night we would go to an hotel, as we each had nearly thirty shillings left of the two pounds apiece with which we left home.

There is a Government Employment Office in connection with the emigrant building, and there we found a good many of the English fellows who came over with us, waiting till the clerk in charge could attend to them. The clerk was writing at a desk and paid no attention to us for a goodish while, and Jack began to get quite indignant at being kept standing so long. At last he put his books away and turned round to us with a big sheet of paper in his hand. "Now, you fellows," he said, "I have a list here of farmers who want men or boys. I am going to read out who the farmer is, where he lives, what he wants, and the wages he will give, and when any one hears what he thinks will suit him he had better speak up, and I will give him a card of directions how to get there."

No one seemed very anxious to take the first places he read out, the wages were so much smaller than they all expected. Some of the grown-up men had letters from an office in London, not a Government office, telling them that men without experience could get forty dollars (about eight pounds) a month as soon as they got to Manitoba. The highest wages the clerk read out was thirty dollars a month for men used to farm work, while for boys, from fourteen to twenty years old, it ran from five to fifteen dollars in most cases.

A good many of the men went away, growling that the whole emigration business was a swindle, and that they could make more money at home. The younger ones, however, had most of them only a little money left, and were afraid of being "stony broke" in a strange place, so one by one they took the places that sounded most promising and got their cards of directions.

There were two fellows wanted for a place called Minnedosa, so Jack and I decided to take them and keep together. One was for a stout lad of eighteen or nineteen to do farm work, wages fifteen dollars a month, that's Jack, and the other for a willing boy of sixteen or seventeen, to do the “chores" round a farm, wages ten dollars a month and that's me. I don't know what "chores" are, and when I asked the clerk if I could do them without experience, he laughed, and said, "You'll be all right; the ‘chores' are everything that everybody else doesn't do."

We got our cards, found out that there would not be a train to Minnedosa till 8 o'clock tomorrow morning, and then went out to see all we could of Winnipeg. First, however, we went to an hotel, to secure a room for to-night and to have a bath and brush our clothes, for we both looked rather grubby and generally "tough," as they say here, after our long railway journey. By the time this was done it was 12 o'clock, and the hotel bell rang for dinner. It was a treat to sit down again to a table with a nice white cloth, with everything fresh and clean and someone to wait on you. The dinner, too, was a great improvement on the "grub" baskets we had on the train.

We hardly knew how to start on our sight-seeing, but decided to take the electric street cars the full length of Main Street, the big business street, first, and then to go on some of the branch lines. We had all the afternoon, and each separate trip only costs five cents, or two-pence-halfpenny.

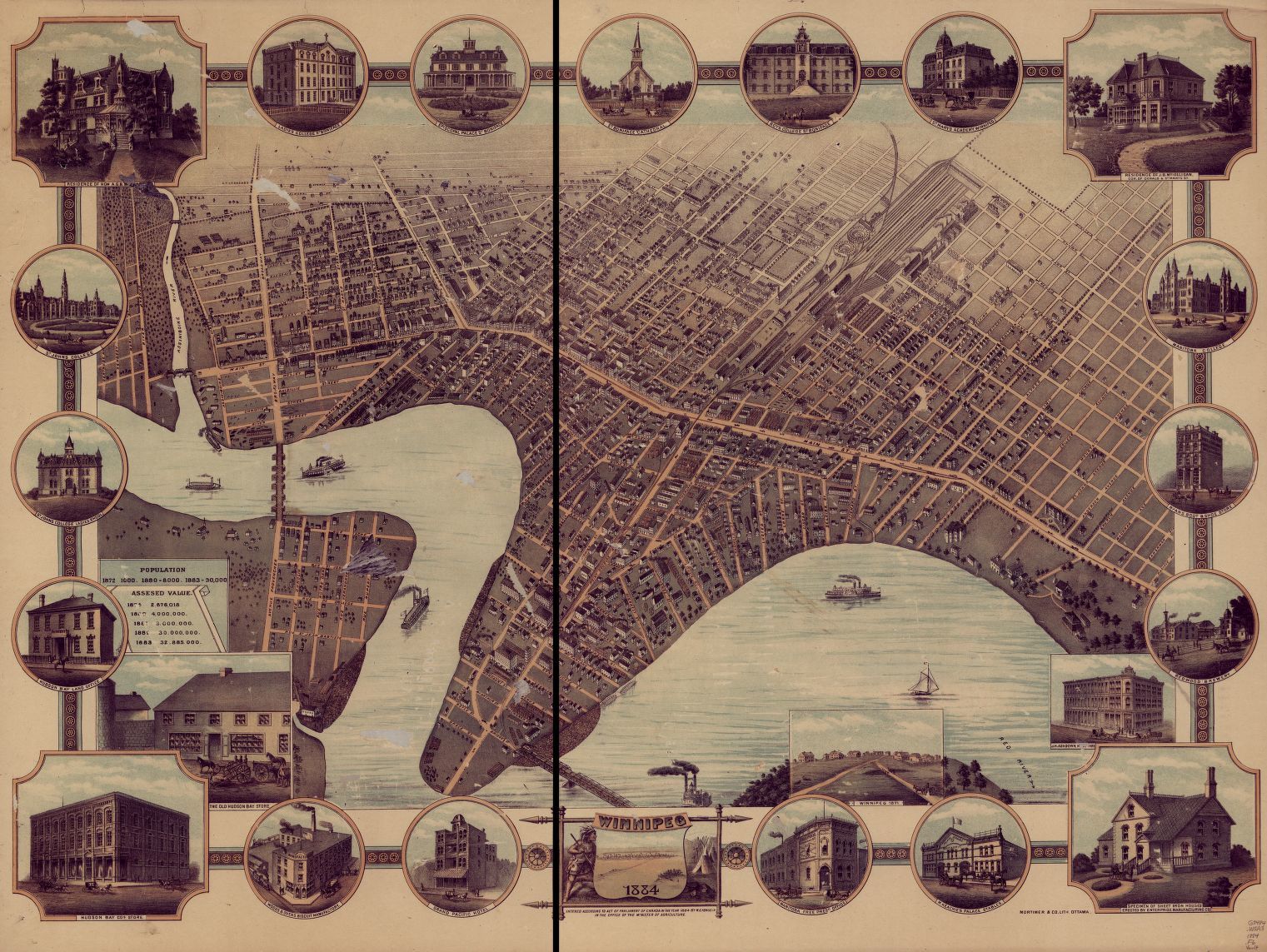

Main Street is a very wide, handsome street; there are a lot of old, shabby-looking buildings near the railway station, but farther down the shops and banks and offices are as fine as in the market-place at home, and the windows are full of beautiful things so somebody must make plenty of money, if I am only to have ten dollars a month. There were a great many people walking along the pavements, most of them well-dressed, and a decent-looking crowd, but in a great hurry, as if they expected to miss a train. The only people not in a hurry were groups of foreign-looking men at the street corners emigrants, I expect, who had not got to work and some roughish-looking fellows hanging about the poorer class of hotels, and they did not look fond of work.

After "doing" Main Street we took several side trips and saw plenty of fine houses, big public buildings and churches. Our last trip was out to St. John's, to see the Church of England College and Cathedral. The college is a good-sized place, like a biggish school at home, but the cathedral is just a little old-fashioned village church, built long ago by the early missionaries, when there were only a few white people here; but it has a nice graveyard, with plenty of trees, and is close to the Red River.

As our train leaves early in the morning, Jack and I have just paid our hotel bill before going to bed, six shillings each for supper, bed and breakfast.

You had better just address my letters to the post-office, Minnedosa, Manitoba, till you get my next letter, where I hope I shall be settled down for a year to the life of a "chore boy."

Your loving son,

Tom Lester.

Gill, Edward, editor. A Manitoba Chore Boy; The Experiences of a Young Emigrant Told From His Letters. Religious Tract Society, 1912.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.