Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Tuskegee and its People: Their Ideals and Achievements edited by Booker T. Washington, 1906.

Resources and Material Equipment

by Warren Logan

When the Alabama Legislature in 1881 passed an act to establish a Normal School for colored people at Tuskegee and appropriated for it $2,000 yearly, it made no provision whatever for land or buildings; these were left to be provided for by the people who were to be benefited by the school. Here was almost a case of being required to make bricks without straw. But as matters have turned out, this neglect was the best thing that could have happened to the school. First it gave opportunity for the employment of those splendid qualities of pluck, self-help, and perseverance which have distinguished Mr. Washington so preeminently in the building of Tuskegee. Moreover, the State has contributed nothing to the school in the way of land or buildings; it has not sought to control the property of the institution, leaving it free to be managed by the Board of Trustees.

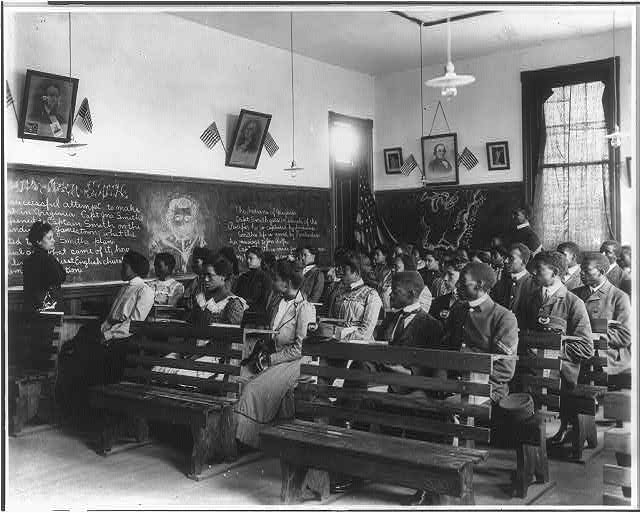

The school was opened on the 4th of July, 1881, in an old church building in the town of Tuskegee, which lies nearly two miles from the present school-grounds. Later in the same year the growth of the school made it necessary to obtain additional room, which was found in a dilapidated shanty standing near the church and which had been used as the village schoolhouse since the war. These buildings were in such bad condition that when it rained it was necessary for the teacher and students to use umbrellas in order to protect themselves from the elements while recitations were being conducted.

Students who came from a distance boarded in families in the town, where the conditions of living were very much like those in their own homes, and these were far below proper standards. Mr. Washington, understanding the great need for colored people to be trained in correct ways of living as well as to be educated in books, determined to secure a permanent location for the school, with buildings in which the students might live under the care and influence of teachers day and night, during the whole period of their connection with the school.

It so happened at this time that there was an old farm of 100 acres in the western part of the town of Tuskegee, well suited to be the site of such a school, which could be had for $500. But where was the money to be found to pay for it? Mr. Washington himself had no money, and the people of the town, much interested as they were in the enterprise, were wholly unable to give direct financial assistance. General J. F. B. Marshall, then treasurer of the Hampton Institute in Virginia, was appealed to for a loan of $200 with which to make the first payment. This he gladly made, and the farm was secured. In a few months sufficient money was raised from entertainments and subscriptions in the North and South (one friend in Connecticut giving $800) to return the loan of General Marshall and pay the balance due on the purchase of the property.

The land thus secured, preparations were at once begun to put up a school building, toward the cost of which Mr. A. H. Porter, of Brooklyn, N. Y., gave $500, the structure being named Porter Hall in recognition of Mr. Porter's generosity. In this building, which has three stories and a basement, all the operations of the school were for a time conducted. In the basement were a kitchen, dining-room, laundry, and commissary. The first story was devoted to academic and industrial class-rooms; in the second was an assembly-room, where devotions and public exercises for the whole school were held, while the third was given op to dormitories.

From this small beginning has grown the present extensive plant at Tuskegee comprising 2,300 acres of land, on which are located 123 buildings of all kinds devoted to the uses of the institution. Some idea of the impression which the size of the school makes upon one who sees it for the first time may be gathered from the remark of a Northern visitor, who, upon returning to his home from a trip through the South, was asked by a friend if be had seen "Booker Washington's school.” ''School?'' be replied. "I have seen Booker Washington's city.''

About 150 acres constitute the present campus the rest of the school-lands being devoted to farms, truck-gardens, pastures, brick-yards, etc. Running through the grounds proper and extending the entire distance of the farms for two or three miles is a driveway, on either side of which, and on roads leading from it, are located the buildings of the Institute. These, for the most part, are brick structures, and have been built by the students themselves under the direction of their instructors in the various building trades. The plans for these buildings have been drawn in the architectural-drawing division of the Institute. While not as ornate as the buildings of some other institutions, they are substantial and well adapted to the uses for which they are intended. The newer buildings, constructed in the last ten years, are more artistic and imposing, showing great improvement in matters of architectural design and finish.

Not only have the students performed the building operations that entered into the construction of these buildings, but they have also manufactured the brick, and have prepared much of the wooden and other materials that were used. We sometimes speak of a man as self-made, but I have never known another great educational institution that could be so described. Tuskegee, itself, is distinctively self-made.

Porter Hall was completed and occupied in the spring of 1888. The following year a brick building for girls was undertaken, and two years later completed. This building, named Alabama Hall, is rectangular in shape and four stories high. It contains a kitchen and dining-room, reception-rooms, apartments of the Dean of the Woman's Department, and sleeping-rooms. There was no special gift made for this building, the money required for its erection being taken from the general funds of the Institute as they could be spared. A wing added later gave more space for dining-rooms and provided a number of sleeping-rooms.

The money used in putting up the buildings at Tuskegee is made to do double duty. In the first place, it provides the buildings for which it was primarily given, and, in the second place, furnishes opportunities for young men to learn the trades which are employed in their construction. Following closely upon the completion of Alabama Hall, there was begun another brick structure to be used as a dormitory for young men. Olivia Davidson Hall bears the honored name of the school's first and only Assistant Principal. Miss Davidson performed a conspicuous part in establishing the school and placing its claim for support before the public. This building is a four-story structure, and the first of the school's buildings for which the plans were made by the teacher of architectural drawing. The plans for all the buildings put up by the Institute are now made in the division of architectural drawing in charge of Mr. R. R. Taylor, a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who is ably assisted by Mr. W. S. Pittman, a graduate of Tuskegee and of the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia.

The need for a building to house the mechanical industries which, until 1892, had been conducted in temporary frame buildings on different parts of the grounds, led to the erection of Cassedy Hall, a three-story brick building standing at the east entrance to the grounds. Cassedy Hall, together with a smaller building devoted to a blacksmith shop and foundry, was used for the purpose mentioned, until three years ago, when all the industries for men were moved into the Slater-Armstrong Memorial Trades Building, at the opposite end of the grounds. Through the generosity of Mr. George F. Peabody, of New York, Cassedy Hall has since been converted into a dormitory for young men, and serves admirably for this purpose.

Phelps Hall, which is the Bible Training School Building, is the gift of two New York ladies who desired to do something to improve the Negro ministry. The building is of wood and has three stories, containing a lecture-hall, recitation-rooms, library, and sleeping-rooms for young men. A broad veranda extends entirely around the building.

Last year there were enrolled fifty-six students for the course in Bible Training, and among them were a number of ordained ministers who have regular charges. Phelps Hall was dedicated in 1892, Dr. Lyman Abbott preaching the dedicatory sermon and General Samuel C. Armstrong delivering an address, which was among his last public utterances.

In the next year Science Hall (now called Thrasher Hall, after the lamented Max Bennett Thrasher) was built. This is a handsome three-story building, with recitation-rooms and laboratories In the first two stories, and sleeping-rooms for teachers and boys in the third story. About this time a frame cottage with two stories and attic was built by the school as a residence for Mr. Washington. This he occupied until the gift of two Brooklyn friends enabled him to erect on his own lot, just opposite the school-grounds, his present handsome brick residence, where he dispenses a generous hospitality to the school's guests and to the teachers of the Institute. The cottage which he vacated was afterward utilized for a time as a library, but now is the home of Director Bruce of the Academic Department.

Alabama Hall, already mentioned, soon proved inadequate to meet the needs of the Woman's Department. A long one-story frame building, having the shape of a letter T, was then erected just in the rear of Alabama Hall. It has been used for girls sleeping-rooms until this year, when it was taken down to make room for a park and playground for young women. There were also successively built for the growing demands of this department, and in the vicinity of the original girls' building. Willow Cottage, Hamilton Cottage, Parker Memorial Home, Huntington Hall, and only this last year Douglass Hall. Huntington Hall is the gift of Mrs. Collis P. Huntington. In design, finish, and appointments it is one of the best buildings owned by the school.

Three years ago a wealthy but unostentatious gentleman, who would not permit his name to be used in connection with his benefaction, gave the school $25,000 for a building for girls, suggesting that the structure should bear the name of some noted Negro. Douglass Hall was erected with this money and named in honor of that great leader of the race, Frederick Douglass. It is a two-story brick building, with a basement in its central section, and contains 40 sleeping-rooms, a reception-room, bathrooms, and a large assembly-room with a seating capacity of 450. In this room the Dean of the Woman's Department holds meetings with the girls on questions of health morals, and manners. The building is heated with steam and lighted by electricity. AH in all, Douglass Hall is the best of the buildings so far built by the Institute, and is a fitting monument to the man whose name it bears.

The Slater-Armstrong Memorial Agricultural Building was completed and dedicated in 1807. Hon. James Wilson, Secretary of Agriculture of the United States, honored the school by his presence and an address on the occasion of the formal opening of this building. It is a brick structure of two-and-a-half stories, with redtation-rooms, laboratory, museums, library, and an office for the use of the Department of Agriculture. In addition to its appropriation of $8,000 for the general work of the school, the State of Alabama makes an annual appropriation of $1,500 for the maintenance of an Agricultural Experiment Station. The plots of the Station and the school-farm are in close proximity to the Agricultural Building, and on these the young men taking the course in Agriculture put in practise the theories which they learn in the class-room. Many important experiments have been undertaken by the Station, of particular interest being those relating to soil building, the hybridization of sea-island cotton with some of the common short-staple varieties, fertilizer tests with potatoes, by which it has been shown that it is possible to raise as much as 266 bushels per acre on light, sandy soil such as that comprising the school-lands, while the average field in the same part of Alabama is not more than 40 bushels to the acre.

The next building of importance to be put up after the Agricultural Building was the Chapel. Another gift from the two New York ladies who gave the money for Phelps Hall made possible this magnificent structure, admittedly one of the most imposing church edifices in the South. It is built of brick, 1,200,000 bricks entering into its construction, all of which were laid by student masons. It has stone trimmings, and in shape is a cross, the nave with choir having a length of 154 feet, and the distance through the transept being 106 feet. There are anterooms and a study for the Chaplain of the Institute. Including the gallery the seating capacity is 2,400. Here all gatherings of the school for religious and other purposes are now held. The great Tuskegee Negro Conference that assembles in February of each year holds its meetings in the Chapel. Near the Chapel are the Barracks, two long, roughly constructed one-story frame buildings, which are used as sleeping quarters for young men until they can be better housed in permanent buildings.

Until 1900 the mechanical industries at Tuskegee were conducted in Cassedy Hall and some adjoining frame buildings. In that year they were moved into the commodious quarters which the then just completed Slater-Armstrong Memorial Trades Building furnished. This building is rectangular in shape, is built about a central court, and covers more space than any other of the school buildings. In its outside dimensions it is 288 feet by 816 feet. The front half of the building is two stories high, the rear half one story. It is constructed of brick, with a tin roof, and, like the other larger buildings at the Institute, has steam heat and electric light. The money for this building came in part from the J. W. and Belinda L. Randall Charities Fund of Boston and the steadfast friend of the school, Mr. George Foster Peabody, of New York. There is a tablet in the building bearing the following inscription: "This tablet is erected in memory of the generosity of J. W. and Belinda L. Randall, of Boston, Massachusetts, from whose estate $20,000 were received toward the erection of the building."

The various shops in this building are fairly well equipped with tools and apparatus to do the work required of them and to teach the trades pursued by the young men. Taking the Machine Division as an example, we find it supplied with one 18-inch lathe, one 14-inch lathe, one 20-inch planer, one 12-inch shaping-machine, one 20-inch drill-press, one 6½-inch pipe-cutting and threading machine, one Brown and Sharpe tool-grinder, one sensitive drill-press, and, of course, the customary tools that go with these machines. The Electric-Lighting Plant is also located in this building. Not only does this Division light the buildings and grounds of the Institute, but it furnishes light to individuals in the town of Tuskegee, which is, at present, without other electric-lighting facilities.

In 1895 the school suffered the loss by fire of its well-appointed barn, together with some of its finest milch cows. This is the only serious fire that has occurred in the history of the school—a record almost unparalleled in an establishment so large. This fact has led to the school being able to get insurance at a lower rate than is generally given to educational institutions. It was not until 1900 that the school fully recovered from the loss of its barn. In this year friends in Brooklyn gave the money with which to rebuild the barn on a larger scale. It was deemed wise not to put all the money into one building, but to erect numbers of smaller ones and locate them so as to minimize the fire risk. Accordingly, plans were made to build a hennery, creamery, dairy-barn, horse-barn, carriage-house, tool-house, piggery, silos, and slaughter-house. All these buildings were at once put up, and are now giving effective service. At present the school owns 47 horses and colts, 76 mules, 495 cows and calves, 601 pigs, and 977 fowls of different kinds. These animals are all of good stock, some of them being thoroughbreds, and are cared for by the students who work in the Agricultural Department.

Dorothy Hall, the building which accommodates the Girls' Industrial Department, was built in 1901 on the side of the driveway opposite the Boys’ Trades Building. This building is the gift of the two New York ladies who gave the Chapel and Phelps Hall. It serves its purpose admirably, the rooms being large, well lighted, and airy. Here are conducted all the trades taught to young women, including sewing, dressmaking, millinery, laundering, cooking, housekeeping, mattress-making, upholstering, broom-making, and basketry. As with the boys' trades, there is a very fair equipment of accessories for proper teaching.

In point of time, the next important building provided was the Carnegie Library, Mr. Carnegie giving $20,000 for the building and furnishings. The structure is two stories high, with massive Corinthian columns on the front. It contains, besides the library proper, a large assembly-room, an historical room, study-rooms, and offices for the Librarian. The building and the furniture are the product of student labor.

In 1901, with $2,000 given by Mrs. Quincy A. Shaw, of Boston, and $100 contributed by graduates of the Institute as a nucleus, the Children's House was built. This is a one-story frame building of good proportions, in which the primary school of the town is taught. It is the practise-school for students of the Institute who mean to teach. A kindergarten has also been established.

Mr. Rockefeller has given a dormitory for boys, which was completed and occupied last year. The lack of adequate sleeping quarters for young men,

The most pretentious building owned by the Institute is the Collis P. Huntington Memorial Building, the new home of the Academic Department, which is the gift of Mrs. Huntington as a memorial to her husband, who was one of Tuskegee's stanchest supporters. It is built near the site of the original building, Porter Hall, which it displaces as the center of the academic work of the school. The outside dimensions are 188 feet by 108 feet. It is four stories in height. Besides recitation-rooms for all the classes, it contains a gymnasium in the basement for young women, and an assembly-room on the top floor capable of seating 800 persons. The finishing is in yellow pine. The buildings of the Institute show a steady progression in quality of workmanship, materials, and architectural design and efficiency, from the rather rough, wooden Porter Hall erected by hired workmen in 1882 to the stately Huntington Hall built by students in 1904.

Located at different points on the grounds and on lots detached are cottages occupied as residences by teachers and officers of the Institute.

The furnishings for all the buildings, as well as the buildings themselves, have been made by the students in the various shops, who at the same time were learning trades and creating articles of use.

The annual cost of conducting the institution is, in round numbers, $150,000. This may seem high, but when certain facts in regard to the work are borne in mind it will not appear exorbitant. In the first place, there are really three schools at Tuskegee—a day-school, a night-school, and a trade-school. Such a system makes necessary the employment of a larger number of teachers than would be needed in a purely academic institution holding only one session a day. Teachers in the trade-school, with special technical training, can be obtained only by paying them higher salaries than are paid to those who simply teach in the classrooms.

Secondly, and principally, it is expensive to employ student labor to do the work of the school. By the time students become fairly proficient in their trades and reach the point where their services begin to be profitable, their time at the institution has expired, and a new, untrained set take their places, so that the school is constantly working on new material or raw recruits. Then, too, Tuskegee is still in the formative period of its growth as to buildings, laying-out and improvement of grounds, and equipment of its various departments. When the school's needs in these directions shall have been met, and the Negro parent shall become able to pay a larger share of the cost of educating his children, the expenses to the public of running the school may be materially reduced.

Money for the support of the school is derived principally from the following sources, viz.: The State of Alabama, $4,500; the John F. Slater Fund, $10,000; the General Education Board, $10,000; the Peabody Fund, $1,500; the Institute's Endowment Fund, $40,000; contributions of persons and charitable organizations, $84,000; a total of $150,000. The individual contributions are, for the most part, small, and come from persons of moderate means. Yet the institution annually receives some large gifts toward its expenses from those who are blessed with wealth.

Especial appeals are made by the institution for scholarships of $50 each, in order to pay the tuition of students who provide for their other expenses themselves largely by their work for the school, but who are unable to contribute anything toward the item of teaching. These scholarships are not turned over to the students, but are held by the institution and assigned for their benefit the aim being to do nothing for students which they can do for themselves, and thus help to develop in them a spirit of manly and womanly self-reliance.

The majority of the large donations, aside from those for endowment, have been for buildings and the purchase of additional farm-lands made necessary by the enlargement of the school’s agricultural work.

What may be regarded as the greatest need of the institution is an adequate endowment which will put it upon a permanent basis and make its future certain.

A gratifying beginning in the building up of an endowment has already been made. It is a fact, still well remembered by the public, that Mr. Andrew Carnegie has given to the endowment fund the princely sum of $600,000. Before that time $400,000 had been collected from other sources for the same purpose, the largest single contribution toward this amount being $50,000 from the late Collis P. Huntington.

As already stated, the income from the present endowment is $40,000, out of which several annuities are paid. This is only a little more than one-fourth of the amount that must be had each year to pay the expenses of the school. It will require an endowment of at least $8,000,000 to yield an income adequate to the present needs of the institution alone.

Tuskegee and its People: Their Ideals and Achievements, Booker T. Washington, editor. D. Appleton and Company, 1906.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.