Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Maori by Raymond Firth, 1929.

The Land and the People

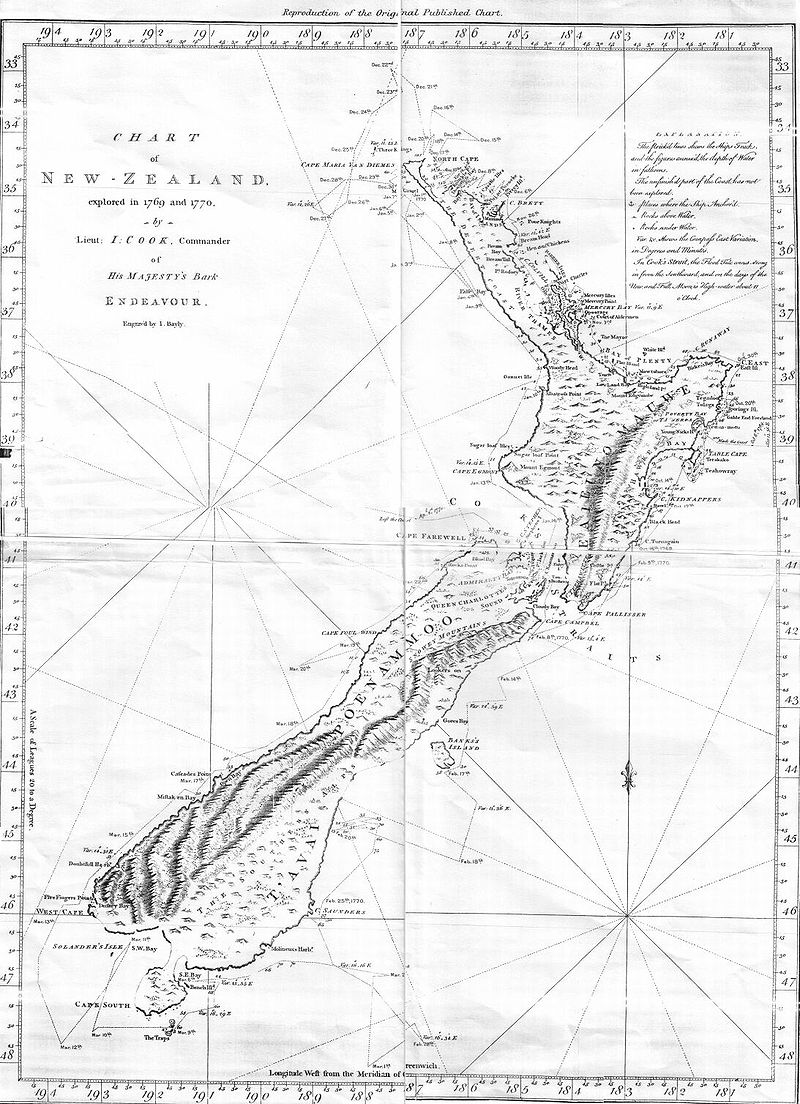

To understand Maori life, one must try and visualize the land of Aotea-roa (New Zealand) as it was in the days before the foot of the pakeha had trodden its shores. Superficially there have been great changes in the last century and a half, the forest has fled before axe and fire, but the essential features of the country remain the same.

There is a great diversity of scenery, from the warm bays of the north to the volcanic lava-strewn mountains of the central plateau, and the cold, white peaks and glaciers of the Southern Alps. In some parts stretches a deeply indented coast-line, forest-clad to the water's edge, brown and rugged cliffs alternating with sandy bays and secluded harbours. The western shores bear a wilder and more grand aspect, the cliffs loftier and more forbidding, fewer inlets, and at times long stretches of beach, surf-battered, running smooth for miles along a wind-swept coast. From a rocky headland, bathed in sunlight, one looks along a beach of black iron-sand, sparkling from a myriad tiny points, bordered inland by grey dunes and the leafy green of the bush, while to seaward the great rollers of the Tasman, moving on in ceaseless procession, shatter themselves with a pulsating roar into lines of hissing white foam.

So one can understand the reference in the Maori watchman's song:—

Whakapuru tonu, whakapuru tonu Te tai ki Harihari; Ka tangi Here Te tai ki Mokau.

Pent back, pent back, the thundering surf resounds On Harihari’s cliffs; With hollow tone the wailing sea Beats on the Mokau coast.

The gannet dives, the gulls cry; no other living thing is seen. Mile after mile stretches the unbroken coast, till in the far distance the eye loses sense of form and shape in the shimmering blue haze. Inland, as covering for the Earth Mother, lies the dark forest with its mosses and drooping ferns, the virgin bush, broken only by the tiny clearings of neolithic man. At times it gives way to rolling open fern-lands, to tussock or swamp or the sage-green manuka scrub. Such is the face of Nature in the home of the ancient Maori.

To turn now to the more prosaic features of the topography. The country on the whole is rugged. A main mountain chain, running parallel with the major part of the coast-line, forms the backbone of both islands, attaining in the north a height of only three thousand to six thousand feet, but much more lofty in the south, culminating in the peak of Ao-rangi, twelve thousand feet above sea level.

Towards the centre of the North Island also occur a series of volcanic peaks and cones, while even the remainder of the country is broken by subsidiary ranges and hilly areas. In the North Island, says the Maori in his myth, these were the result of the convulsions of the fish of Maui, which, being hauled up to the surface by that culture-hero to be as a source of food for man, was thoughtlessly slashed and tasted ere the tapu could be lifted from it, and so struggled till it died.

Hence come mountains and valleys as the wrinkles and folds in its skin. The land is well watered, streams and rivers being plentiful, and though as a rule somewhat swift, offering in their lower reaches scope for canoeing. The lake system of the country is well developed. The lakes are concentrated mainly in the central district of the North Island, where they are due to volcanic action, and the more southerly part of the South Island, considerable variation owing to the great range of latitude of these islands (34' S.-47' S.).

It is almost sub-tropical in the Northern Peninsula, but grows distinctly colder as one approaches the south. In former region, even the depth of winter sees no snow. In the latter the climate is still fairly mild, hut snowfalls are comparatively frequent on the higher levels. This climatic variation had considerable effect upon the situation of the natives in the corresponding areas, especially in the matter of clothing and of cultivated foods.

In general there is no lack of rain, though here again there is considerable variation, owing to the interception of the rain-bearing winds from the west by the central mountain chain. For this reason the bush of the western districts, more particularly in the South Island, tends to be more luxuriant. There is no rainy period, as in the Tropics, and the seasonal change, though marked, is by no means extreme.

The flora presents a great diversity, both in number of species and variety of plant associations. The lowland and mountain forests are generally of the sub-tropical rain-forest type, dim-lit, sombre and evergreen, the giant trees rising from dense masses of undergrowth, luxuriant in ferns and mosses, with trailing epiphytic plants perched on the massive trunks of their hosts.

The dark leaf-mould is underfoot tree ferns and the nikau palm rise gracefully at intervals, while the supple-jack and the clinging bush-lawyer lurk to retard the step. In the flora of the higher mountain sides the beech forest holds the field, to be replaced at greater altitudes by the sub-alpine vegetation, low and stunted, with its diversity of small plants. In some parts of the country in former times grasslands or tussock were to be seen, the latter denoting, maybe, a less fertile region, but more frequently the open land was clothed with the ubiquitous bracken or the sage-like manuka scrub.

Of animal life in pre-European days, there was a remarkable scarcity, except as regards avifauna. The only indigenous land mammal was the bat; lizards, and that hoary survivor of bygone ages, the spined tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), represented the reptiles; the rat, which the Maori claims as an immigrant in the ancestral canoes, and the dog, a domesticated type, made up the tale of animals.

Of bird life, however, there was no lack. The gentle pigeon, the parrot of harsh voice, and the silver-tongued parson-bird or tui—kukupa, kaka, and koko, the trio of onomatopoeic name—were abundant, and furnished many a toothsome meal to the forest-dweller. Then the kiwi, the quaint Apteryx, the kakapo or ground parrot, and the thieving weka, the flightless rail with his eerie cry, with bell-bird, robin, owl, parakeet, kea, huia, and many other lesser species also peopled the bush.

Swamp, shore, and the open sea, too, each had its feathered folk. Altogether there were over two hundred species in New Zealand of great diversity of type and habit. Fish of many species were plentiful round the coast, about thirty-five kinds being used for food, while the eel and sometimes other freshwater fish, together with the succulent crayfish, inhabited inland lakes and streams.

Geologically the country presents a number of features of interest, but for our purpose the main question lies in the availability of raw material for implements. The nature of the mineral resources denied to the Maori the use of metals. Suitable stone for tools, however, occurred in many parts, while obsidian and nephrite were to be found in a few localities.

Firth, Raymond. Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Maori. George Routledge & Sons, 1929.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.