Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Mexico of the Mexicans by Lewis Spence, 1917.

The educational system of Mexico has been reorganised on modern lines. In the old days the schools were under ecclesiastical rule—by no means a desideratum. Colleges were founded so early as 1530, and in 1553 the University of Mexico came into being. This institution, however, never achieved a position compared to that of the greater South American Universities, but, this notwithstanding, education continued to flourish in Mexico; and when at last the Spaniards were expelled from the country, increased efforts were made to introduce educational reform.

Matters were, however, still under the discipline of the Church, and it was found that for this reason but little could be achieved. The subjects taught in those earlier days were, for the most part, Latin rhetoric, grammar, and theology, which curriculum was supposed to furnish the student with a liberal education. In 1833 the usefulness of the University of Mexico became doubtful, its labours were suspended, and in 1865 it passed out of existence.

After the overthrow of Maximilian, its place was taken by a number of individual colleges, institutions of law, medicine, and engineering being founded in 1865, and proving much more suitable to the modern requirements of the country. Good schools, too, began to spring up in the provinces; and in 1874 there were no fewer than 8,000 of these, with an attendance of 360,000 pupils.

When visiting Mexico at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Humboldt professed himself greatly surprised at the development of education in the capital, and at the number and worth of its scientific institutions. But the Spanish-American has always been most amenable to educational and refining influences. Indeed, few races in the world exhibit such signs of enthusiasm for culture as do those of Latin-America. The movement was strongly fostered by President Diaz, who, indeed, regarded it as the basis of Mexican existence. Diaz made a thorough personal study of educational methods and requirements, and may indeed be said to have founded the present machinery of instruction in vogue within the Republic.

A National Congress of Education was convened in December, 1899, and also in the following year; and its provisions were carried into effect in 1892 through a law regulating free and compulsory education in the Federal District and national territories. Prior to this, Mexican public education had been under the supervision of a company known as the Compañia Lancasteriana, so called after Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838), the English educationist whose system was matter for so much controversy at the beginning of last century, and which consisted to a great extent of instruction by monitors and mnemonics.

This doubtful and antiquated method was now abandoned, and the schools taken in charge by the Department for Public Education; but no comprehensive or far-reaching scheme was arrived at until 1896, when a simple yet liberal plan was constituted. At first, the various States objected to educational interference within their boundaries; but, later, they came to see the evils accruing to a lack of uniformity. In 1904, over 9,000 public schools were opened for instruction, with an enrolment of 620,000 pupils. Nearly 3,000 of the schools were supported by the municipalities, and there were also over 2,000 private and religious establishments with 135,000 pupils.

Secondary instruction was by no means neglected. for at the last date for which figures are available there were 36 secondary establishments with nearly 5,000 pupils, and 65 schools for professional instruction with 9,000 students, of which 3,800 were women. This last statement shows how thoroughly modernised the educational movement has become in the Republic.

A quarter of a century ago, Mexican women would never have dreamed nor have been desirous of participating in the benefits of the higher education, but now their keenness to embrace professional careers is intense. It is, of course, extremely probable that the relative proximity and example of their Northern neighbours in the United States, where female education has made such advances, has had much to do with their enlightenment, for many Mexican women, like their brothers, are now educated in the United States, whence they return with the most modern opinions regarding instruction, erudition, and general culture.

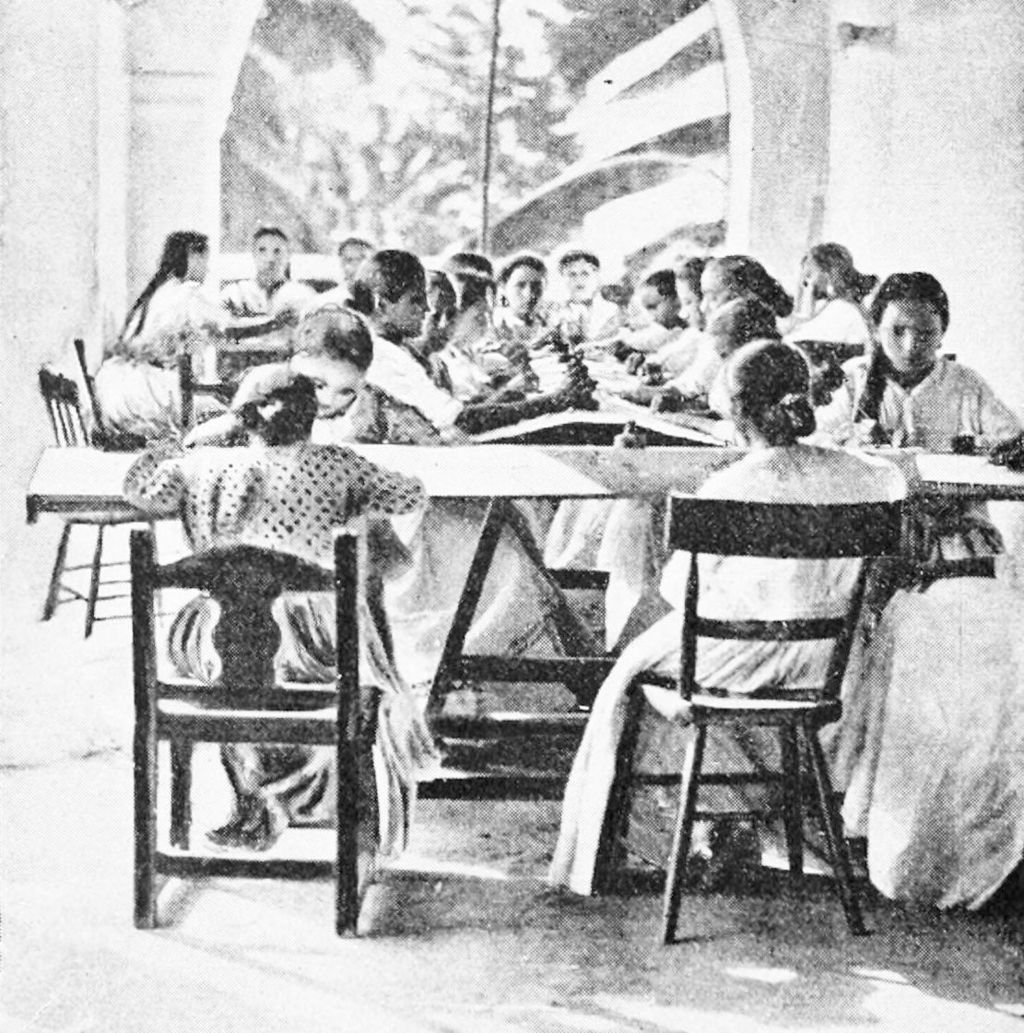

The curriculum of the Mexican public schools is carefully graded. In the preparatory departments, Spanish grammar, arithmetic, natural science, the history of his native land, practical geometry and drawing, and singing are taught the boy, as well as gymnastics and physical drill. These last two items are replaced in the girls' curriculum by sewing and embroidery.

In the higher grades, English is compulsory. Religious education is wisely banned from the schools of Mexico, for the terror of priestly interference and domination has burned itself so deeply into Mexican memory that there is no desire to encourage a recurrence of these evils. In the place of religion there is instruction in moral precepts and civic ethics. Stress is laid on the virtues of temperance—instruction that is sadly necessary in Mexico, where the ravages of the national beverage may be witnessed on every hand—and the children are taught to be good citizens and good Mexicans. Many of the schools have their temperance societies, and as far as is possible the teachers are drawn from the ranks of total abstainers.

The children appear happy and contented, intelligent, and eager for instruction, and their course of study by no means unfits them for the usual childish sports. Night schools flourish where the child may continue its education after leaving school, or the grown-up person may acquire that instruction which in early life he or she has been unable to obtain.

There are excellent training schools for teachers of both sexes. Many of these are Mixtecs and Zapotecs from the Southern States, the descendants of a highly civilised people who did much to spread the use of the old native calendar, the source of all native wisdom, throughout Mexico. In all these schools, not only instruction, but books and other apparatus are entirely free, even in such of the training colleges where the students of the professional classes resort.

The Mexican peon, when educated, does not seek to abandon the labour of his forefathers. He does not, as a rule, desire to become a clerk or to exchange his zarape for the black coat of commerce. This attitude may be regarded as lacking in ambition. On the other hand, it may prove his wisdom in avoiding the pitfalls of the life of the lesser bourgeoisie.

Spence, Lewis. Mexico of the Mexicans. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1917.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.