Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From The Travels of Mirza Abu Taleb Khan, 1814.

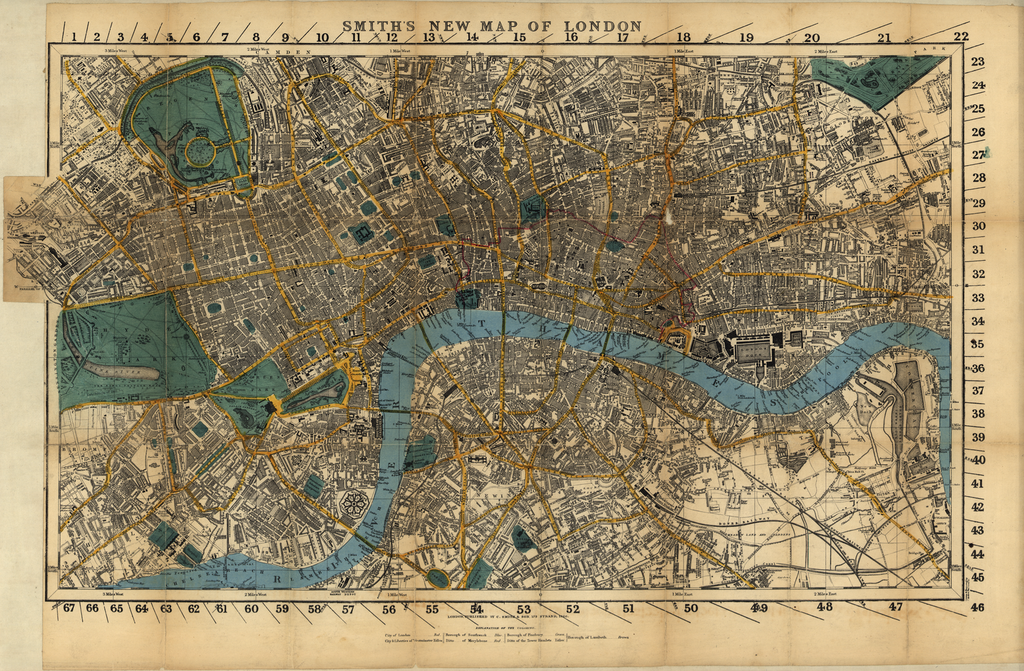

London is the capital of the Empire, and is the largest city I have ever seen: it consists of three towns joined together, and is twenty-four miles in circumference: but its hamlets, which to a foreigner appear a continuation of the city, extend several-miles in every direction; and new streets are each year added to the town, the houses of which are frequently bought or rented before they are finished, and in the course of twelve months are completely inhabited.

Thus during my residence there, ten new streets were added to the town. The houses in London are generally built of brick, though a few of them are of hewn stone: they are commonly four stories high, and have regular rows of glazed windows in front. A few of the noblemen's houses have courts or porticoes before the door, which add to their grandeur. The roofs are sloped like a tent, and are covered either with tiles, or thin stones called slates. The interior is divided and furnished like those already described in Dublin; and the streets and shops are also lighted at night, in the same manner. The shops are in regular rows; and are very rich, extensive, and beautiful, beyond any thing I can describe.

The greatest ornament London can boast, is its numerous squares; many of which are very extensive, and only inhabited by people of large fortune. Each square contains a kind of garden in its center, surrounded with iron rails, to which every proprietor of a house in the square has a key, and where the women and children can walk, at all hours, without being liable to molestation or insult.

In this city the coffee-houses are not so numerous as in Paris: here is scarcely a street, however, in which there is not either an inn, hotel, or coffee-house, to be found: many of these have a magnificent appearance, and are on so extensive a scale, that in the London Tavern they can prepare a dinner for five hundred persons of rank, at a few hours notice. I frequently dined at this tavern, with the Indian Club, by invitation; and although several other large parties were assembled there at the same time, we were not sensible, either from a want of attendance, or from any noise or confusion, that any other persons were in the house.

Of the many admirable institutions of the English, there was none that pleased me more than their Clubs. These, generally speaking, are composed of a society of persons of the same rank, profession, or mode of thinking, who meet at a tavern at stated times every month, where they either dine or sup together, and confer with each other on the topics most interesting to them, or discuss such matters of business as, for want of room, could not be easily done in a private house.

These societies frequently consist of one or two hundred members; but, as seldom above thirty or forty assemble at one time, they are easily accommodated. The absent members pay a small fine, which is carried to the account of the expences of the dinner, and the remainder is paid by those present.

There are a great variety of these clubs. Some are appropriated to gambling, or chess; others are entirely composed of painters, artists, authors, &c. &c. The Indian Club consists of a number of gentlemen who have resided for some years in the East.

At these clubs, no person but a member is admitted, without a particular invitation; and, in order to become a member, every person must be ballotted for; that is, his name and general character are submitted to the society; and if any gentleman present objects to him, he is immediately rejected.

They have also societies of nearly a similar nature, which meet at the house of the president, where they are entertained with tea, coffee, sherbet, &c. Of this kind is the Royal Society, who meet every Sunday evening at the house of Sir J. Banks, where all new inventions are first examined; and if any of them are found deficient, they are rectified, by the joint consultation of the members. All the great literary characters assemble here, and submit their works to the inspection of the society. Through the kindness of the President, I was frequently present at these meetings, and derived much mental satisfaction from them.

I also frequently attended the meetings of the Musical Society, at the house of Lady Charlotte, where I was always much delighted by the harmonious voices and skill of the performers.

In London there is an Opera, and several Play-houses, open to every person who can pay for admission. As these differ but little from the Play-houses described in my account of Dublin, it is unnecessary to say more respecting them. There are also so many other places of public amusement, that a stranger need never be at a loss to pass his lime agreeably.

A philosopher named Walker lately hired one of the old Play-houses, in which he exhibited, every night during the summer, an astronomical machine, called an Orrery, by which all the revolutions of the planets and heavenly bodies were perfectly described. From the centre of a dome twenty yards in height was suspended a glass globe, in which a bright lamp was burning that represented the Sun, and turned round, like the wheel of a mill, on its axis.

Next to the Sun was suspended a small globe that represented Mercury; a third representing Venus; a fourth, the Earth; and a fifth, the Moon: the sixth was Mars; the seventh, Jupiter, attended by four satellites; the eighth, Saturn, with five attending satellites; and the ninth, Georgium Sidus, a lately-discovered planet, with six attending satellites. All these globes were put in motion by the turning of a wheel; and exhibited, at one view, all the revolutions of the Solar system, with such perspicuity as must convince the most prejudiced person of the superiority, nay, infallibility, of the Copernican System. I was so much delighted by the novelty of this exhibition, and the information I received from it, that I went to see it several times.

The English have an extraordinary kind of amusement, which they call a Masquerade. In these assemblies, which consist of several hundred persons of both sexes, every one wears a short veil or mask, made of pasteboard, over the face; and each person dresses according to his or her fancy. Many represent Turks, Persians, Indians, and foreigners of all nations; but the greater number disguise themselves as mechanics or artists, and imitate all their customs or peculiarities with great exactness. Being thus unknown to each other, they speak with great freedom, and exercise their wit and genius.

At one of these entertainments, where I was present, a gentleman entered the room dressed in a handsome bed-gown, night-cap, and slippers, and, addressing the company, said he paid several guineas a week for his lodgings above stairs; that they had kept him awake all night by their noise; and that, notwithstanding it was near morning, they did not appear inclined to disperse; they were, therefore, a parcel of rude, impudent people, and he should send for constables to seize them. I thought the man was serious, but my companions laughed, and applauded his ingenuity.

Several of the ladies of quality permit their acquaintances to come to their houses in masquerade dresses, previous to their going to the public room, where they exhibit their wit and skill at repartee.

They have other public, amusements, called Balls, which are confined to dancing and supper; but there are so many private entertainments of this kind given, that the public ones are not well attended in London.

I one day received an invitation card from a lady, on which was written, only,

“Mrs.⸺ at home on ⸺ evening"

At first, I thought it meant an assignation; but, on consulting one of my friends, I was informed that the lady gave a Rout that night; and that a rout meant an assemblage of people without any particular object; that the mistress of the house had seldom time to say more to any of her guests than to inquire after their health; but that the servants supplied them with tea, coffee, ice, &c; after which they had liberty to depart, and make room for others. I frequently afterwards attended these routs, to some of which three or four hundred persons came during the course of the night.

Khan, Mirza Abu Taleb. Travels of Mirza Abu Taleb Khan in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1814.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.