Prehistoric Britain

No written records of Britain exist before its contact with Greek and Roman writers. Prior to the 1st century BCE, its residents passed their histories orally from one generation to the next. They followed variations of Celtic customs once seen throughout much of Europe, though the Celts were not the island’s original people. Its earliest continuous inhabitants walked there while it was still connected to mainland Europe. By about 4000 BCE, they had formed agrarian settlements and begun building massive stone monuments such as Stonehenge. The Celts arrived in waves by boat from 2000 BCE on. They installed themselves as the island’s nobility, forming an Iron Age culture based on druidic education and chariot warfare.

The Roman Conquest

The first Roman expeditions to Britain were led by Julius Caesar in 55 and 54 BCE as part of his Gallic campaign. During his two visits, Caesar won a few minor battles and built alliances with several local tribes. They established trade relations and the beginnings of cultural exchange. True Roman occupation did not begin until 43 CE, when Emperor Claudius organized an invasion force of about 40,000 men. The Romans expanded from Britain’s southern shores to its approximate modern border with Scotland, famously delineated by Hadrian’s Wall. Roman influence in England and Wales set them apart culturally from Scotland and Ireland, which remained independent.

The Fall of Rome and the Anglo-Saxons

By the 4th century CE, Rome was struggling to defend its capital city, let alone protect its outer provinces. It withdrew its legions from Britannia in self defense, leaving its citizens vulnerable. The primary threat to the island came from Angle, Jute, and Saxon raiders—Germanic peoples who had settled along the North Sea coast. In 449, they invaded the island in force. Like the Celts before them, the Anglo-Saxons were probably a minority in Britain. Instead of replacing the native population, they ruled as a noble class over small kingdoms. Their domains formed the heptarchy of Essex, Northumbria, Wessex, Sussex, Mercia, East Anglia, and Kent. Of these, Northumbria, Wessex, and Mercia were most powerful.

The early Anglo-Saxons practiced Germanic paganism. By 600 CE, however, the kingdom of Kent had converted through Christian missionary efforts. The next century saw the rest of the kingdoms convert and Mercia grow to dominate them all. The Kingdom of England formed under the Mercian Æthelstan in 927. The Anglo-Saxons, once Germanic raiders themselves, faced invasion by Danish Vikings from the 8th to 10th centuries. Initial pillaging of monasteries like Lindisfarne gradually led to real conquest. The Danes gained a foothold in Jorvik, now York. In 1016, Cnut the Great invaded England and claimed its kingship. He later gained the titles King of Denmark and Norway, forming the North Sea Empire. England returned to Anglo-Saxon hands by 1042.

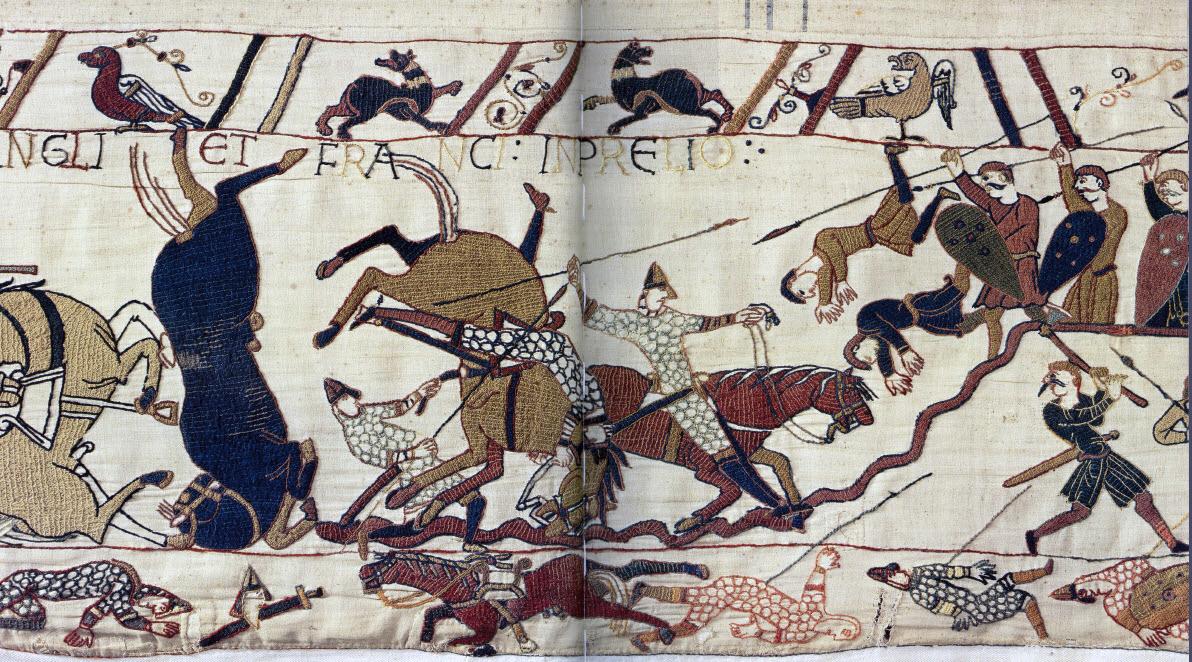

The Norman Conquest of England

The Anglo-Saxons and Danes battled for control of England, but their power struggles came to an abrupt end. In 1066, the Normans, a separate Viking branch that had settled in France, launched an invasion under Duke William of Normandy. William pressed his claim on England with Papal backing. The king of the Anglo-Saxons, Harold Godwinson, had fended off the invasion of Norwegian King Harald Hardrada just a month before. The Anglo-Saxons and Normans met at the Battle of Hastings, which resulted in the death of Harold and the end of Anglo-Saxon rule.

The Normans assumed control of England and began replacing the Anglo-Saxon nobility. The Anglo-Saxons scattered to Ireland, Scotland, and the Continent. Some became members of the elite Varangian Guard of the Byzantine Empire. In 1169, the Anglo-Normans began a separate conquest of Ireland, though English control over the island would not solidify until the 1500s. The descendents of William produced famous English kings like Richard the Lionheart and King John. The House of Normandy ruled until 1154, when the related House of Plantagenet succeeded.

The Renaissance Era

The Middle Ages of Britain are generally thought to have ended with the War of the Roses. Between 1455 and 1487, the competing houses of Plantagenet and and Lancaster fought for control of the crown. The civil war ended with the destruction of both families’ male lines. A separate branch of the Lancasters emerged with the throne under King Henry VII Tudor. The Tudor dynasty would prove to be one of the most influential in English history. Henry VIII, famous for his many wives, split from the Catholic Church to form the Protestant Church of England.

Both Henry and his daughter, Queen Elizabeth I, built England’s navy into a military force capable of matching that of the Spanish. In 1588, Elizabeth oversaw the defeat of the Spanish Armada, cementing England’s position as a major naval power. This investment in the British fleet allowed the English to take a leading role in Europe’s Age of Exploration. The British were part of a second wave of colonizers, following the example of the Spanish and Portuguese. Its earliest colonial efforts took place in Ireland. After centuries of nominal authority, King Henry VIII introduced new laws meant to suppress Irish culture and bend its industries to English benefit.

The English Civil War

James I’s son, Charles I, inherited a throne plagued by religious strife, political tensions, and global economic competition. His disputes with Parliament over the rights of a monarch meant he could not raise funds. For 11 years, he did not call Parliament into session at all. But it was his efforts to unify the Churches of England and Scotland that prompted rebellion, civil war, and his eventual death. Without funding, Charles could not prevent Scotland’s retaliatory invasion of Northern England. By 1642, the kingdom had divided between those loyal to the king and those loyal to the Parliament. In the three civil wars that followed, Parliamentary forces led in part by Oliver Cromwell eventually imprisoned the king and beheaded him in 1649.

Cromwell served as Lord Protector of England during its brief period as a commonwealth. By 1660, however, the Stuarts had been restored to the monarchy. Their brief reigns continued to suffer from internal turmoil. Stability returned at last in 1688, when the Dutch Prince William of Orange deposed the last Stuart, James II, to become King William III of England, Ireland, and Scotland. In 1707, the crowns and parliaments of Scotland and England united to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Colonial and Industrial England

In the wake of the Civil War, England regained its footing as a firmly Protestant monarchy held in check by a strengthened Parliament. During the 18th century, the British Empire expanded its colonial holdings in the Americas, Australia, India, Africa, New Zealand, and the East Indies. The colonies supplied a massive influx of raw goods and cheap labor for the British crown. They provided the foundation for industrialization, or the organization of large-scale manufacturing industries within a nation.

Colonialism required the subjugation of cultures thousands of miles from the British Isles. This led to frequent warfare and rebellion. The British military responded by mastering battlefield tactics, supply lines, and troop movement. Despite its efforts, many of these colonial wars resulted in costly defeats. In 1776, 13 English colonies in North America declared independence, forming the United States of America in 1783. A British invasion of the US in 1812 led to an embarrassing defeat. Protracted wars in India and Africa further dampened English enthusiasm for empire. The Crimean War from 1853 to 1856 introduced modern warfare technologies and revealed the inadequacy of British field medicine.

World War I & II in England

The World Wars of the 20th century brought warfare to the doorstep of the United Kingdom. World War I, originally a conflict between European royal families, soon spread across their colonies. Between the World Wars, Ireland fought a successful war of revolution. While Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom, the majority of the island established itself as a separate nation. World War II brought direct devastation and the threat of invasion by Nazi Germany. German bombers leveled parts of London during the ‘Blitz,’ a sustained bombing operation meant as a precursor to invasion. Led by Winston Churchill and King George VI, the UK contributed to the eventual victory of the Allies, at the cost of much of its prestige and infrastructure.

England and the Modern United Kingdom

Following World War II, the British Empire entered a period of gradual diminishment. More colonies left the empire, both peacefully and through bursts of violence. India and Pakistan gained their independence in 1947. By 1997, it had relinquished the last of its colonies, Hong Kong, back to China. Modern England remains a member of the United Kingdom. Its current monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, is the longest-reigning ruler in English history.

References

Dyer, Christopher. Everyday Life in Medieval England. Cambridge University Press. 2000.

“England.” WorldAtlas, WorldAtlas, 7 Apr. 2017, www.worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/europe/england/ukelandst.htm.

Hibbert, Christopher. Life in Victorian England. New Word City. 2015.

Jenkins, Simon. A Short History of England. Profile Books. 2011.

Kumar, Krishan. The Idea of Englishness: English Culture, National Identity and Social Thought. Ashgate Publishing. 2015.

Olsen, Kirstin. Daily Life in 18th-Century England. 2nd Ed. ABC-CLIO. 2017.

“The World Factbook: United Kingdom.” Central Intelligence Agency, Central Intelligence Agency, 12 July 2018, www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/uk.html.

White, R.J. A Short History of England. Cambridge University Press. 1967.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.