Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Home Life in Italy: Letters from the Apennines by Lina Duff Gordon, 1908.

The Festival of the Madonna

The morning was clear and beautiful.

It was the second Sunday in July, the day specially set apart for the Festival of the Madonna. The holy image was to be carried in procession through the street of Campia, and there was to be a special service and every one would beseech God and the Holy Virgin to stave off the great calamity, and let this year at least be free from a devastating hailstorm.

Everything was being done to make the day acceptable to God, there was no one in Campia who underrated its importance. Raimondo, just before he left for America, told me that it was the plain duty of every one to subscribe to the Festival Fund, and when a few days later a peasant called with the subscription list we all gave something. Sums from a half to two and a half lire had been subscribed, so Rosina, who aspired to be better than her neighbours, gave three.

Long before ten o'clock we started for the village, but it was already hot and there was very little shade on the road. Rosina and the boys carried large baskets full of provisions, for they had no intention of returning to San Lorenzo before night. The Cominelli's house was still empty, and Rosina meant to cook the meals there. To judge by the large number of wine bottles, she must also be hoping to do a little illicit trade.

The band struck up before we reached the first houses and the children hurried on. Rosina, however, could not be hurried. She flapped her handkerchief over her face, and perspired and groaned, and implored me to walk slower. At last we reached the Cominelli's house, and she threw open the doors and shutters and busied about.

I stood on the back stairway which led to the courtyard and enjoyed the sun. It seemed to saturate the white buildings and everything was hot to the touch. Across the water Monte Moro looked cool and majestic.

All at once some one began to sing next door, beginning boldly in the middle of a song:—

'Guarda che bel colore

Senti che buon profumo'

'Ghita,' I shouted, 'Ghita.’

'Ah, it is la signora,' she said, coming into the stairway and leaning her arms on the parapet. 'You are getting sunburnt,' she remarked.

'Yes,’ I answered, rather proud of my tanned skin, 'look at my arms.'

'Italian ladies,' she said, 'are afraid of the sun.'

'Yes—I've seen them,' I answered, 'they all look as if they'd been brought up in the cellars.'

Ghita laughed, and her white teeth shone in the sun. Then she picked a faded carnation from one of the pots on the parapet and threw it down into the yard.

'Then you must think my dark skin quite beautiful? I've always been ashamed of it!'

'If you weren't in good health,' I answered, 'you wouldn't have such a glorious colour.'

'You are right,' she said, 'the signore are always ailing.' Just then the band struck up another tune. 'Let's go to hear the music together, I won't be a moment.’

I walked down the passage into the shady street and round to the front door of their house. I had meant to go in and wait for Ghita, instead, I stood looking up the street.

What were they hanging out of the windows? I could see Giacomina busy upstairs. She was holding out a bedspread, a beautiful thing all red and yellow. She let it hang right down and on the sill; in order to keep it in place, she put a pillow, an ordinary pillow, in a clean white pillow-case. Every house was being decorated in the same way. Just above me, from the window of the room where Toni kept the piano, hung a large white bedspread.

Next door, the house of Renzi Faustino, there were several windows and not enough bedspreads to go round, it seemed. The girl had just hung out a dark blanket and was suspending a lace curtain over it. Then she put a pillow on the sill, just as Giacomina had done, and as every one else was doing. Some of the pillow-cases had pink check covers, and a very few were pale blue.

It was a simple but very effective form of decoration. The whole street looked gay. No doubt housewives vied with each other in the possession of bright bedspreads, and I understood now why Giacomina had once shown me the red and yellow one with such pride; it was one of her most cherished possessions.

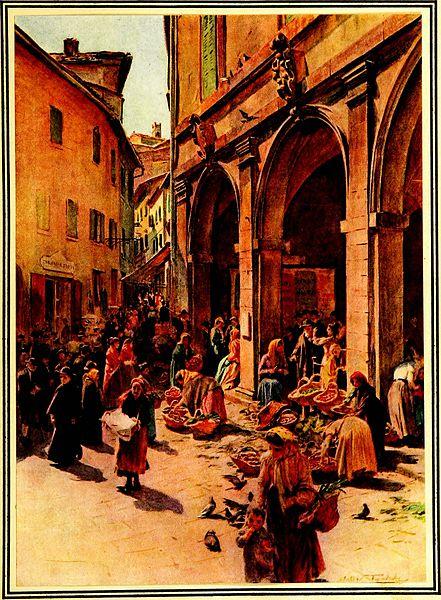

I did not wait for Ghita, but walked on to the fountain. The street had been swept and tidied. Decorative arches had been put up at intervals, covered with green twigs and paper flowers. A prickly plant, which grew higher up on the mountain, had been gathered and dipped in whitewash. Stuck among the green it looked like silver.

There was a good sprinkling of people by the fountain, but the street leading to the piazza was crowded. A great many villagers were there, and a great many other people who had come from neighbouring places. On every side I saw happy, expectant faces. Every one was dressed in their best, all the male part of the population had on new shirts, or they ought to have, for such was the custom.

Rosina had sat up until midnight finishing shirts for the boys. The women all had their hair carefully dressed, and lovely thick hair they had too, but the men usually grew prematurely bald on account of their habit of always wearing a hat, both indoors and out. I once asked Nino whether he slept with his hat on, but he shook his head. I am certain, however, that he never took his hat off until he was in the bedroom, and that first thing in the morning it was clapped on again.

The band, which had finished playing in the piazza, came trooping up the street to the fountain, and formed up in a circle. People crowded after and stood round whilst it played. One or two favoured small boys were allowed to stand within the ring and hold up a sheet of music. After playing a few tunes the band trooped off to the new road and played a few tunes there, and then off again to another spot.

I met Nino in the road and greeted him.

'Tell me,' I asked, 'the procession is to be this morning, isn't it?’

'No, signora, between four and five this afternoon.’

'But why so late?'

'Because,’ he answered, 'it will be hot, and the Madonna is heavy.'

The bells pealed out and every one moved towards the church, where two babies were being christened. The band had taken up its place close to the doors and was playing a gay tune. We loitered in the sunny piazza until the tune was finished.

Then we hurried into the church, anxious to find a seat. Men and boys crowded in at the side door, the women all entered the large door at the back. Every seat was filled.

Coming from the bright sunshine the church seemed like a cavern, but my eyes soon became accustomed to the mysterious dimness. I could see the decorations and the suspended draperies, and the special altar which had been erected in the body of the church. On it stood the image of the Madonna, dressed in blue and silver.

Mass was conducted by two priests from neighbouring villages, and although present our priest took but a minor part. Toni was absent from the organ loft, his place being taken by a blind organist, specially engaged for the occasion. He played very well, but I missed Toni's spirited tunes.

Beside me sat two girls. They both wore hats, and for this reason they ought to have been ladies, for no peasant woman wore a hat in church; but their manners betrayed them. The stout one, with a cast in her eye, wore a fawn dress in tolerably good taste, but the younger, dark and slim, had on a pink hobble skirt and a cheap lace blouse. They whispered together during the service, grinned at each other, and spent very little time on their knees. It was just affectation of manner, for I am sure they reckoned themselves to be pious. If you wear a hat you must behave like a lady, and once having exchanged the village for the town, they did not feel they could come back and behave like they used to. What a pity it was that they were unable to discriminate between ladies, and took as a model upstarts like themselves.

Before the end of the service, several women hurried out to attend to their respective dinners. No sooner had they left the building than the bandsmen hurried after them, so that when mass was over and we all came out into the sunlight, the band was in the piazza and welcomed us with a sentimental waltz, even before the last strains of the organ had died away.

Girolomo was a person of importance, he had the responsibility of all the arrangements. He walked about overflowing with goodwill, in his hand a piece of paper covered with notes in a large hand. He was responsible for the band amongst other things, and had to see that it was supplied with plenty of wine. He had ready a storeroom for the instruments when not in use, and in order that the bandsmen should be properly provided with dinner, he had billeted them out on various families. Just now he stood in the piazza, a large tray in his hands. On the tray were tumblers filled with wine which he was offering the bandsmen, and coaxing them to take. A table had been brought out, and Gioan stood by it filling up more glasses. Then he collected the tumblers and carried them indoors to be rinsed. None of the women took any part in the matter.

Those who had no dinner cares strolled about in the heat, looking for friends. I saw Gheco with his mother and Appollonia, and with them were Apollonio's mother, sister, and brother. It was significant that they should be together—it pointed to an engagement, or at least to the first preliminaries between the parents of Apollonio and Gheco.

All at once the piazza emptied. It was dinner time.

I found Bortolo giving the final stir to the polenta. Even on this great day every one ate polenta. Every housewife spread a clean white cloth on the dinner table. Rosina had prepared a tame rabbit with herbs and fat, butter, and oil, and fried onions, which was delicious.

No sooner had we finished the meal than a deputation came in to ask whether the room might be used for a dance. Rosina made no objection and the room was cleared. A fat man in velvet trousers, carrying an accordion, came in and began to play. The company were all strangers to me, so I did not remain. Instead I strolled up the street, which was still empty. Sounds of talking and laughter came from all the houses.

After paying a visit to Giacomina I went on to the inn. It was crowded. Teresina was bustling about with glasses, taking orders, Nino and his old father were busy bringing bottles up from the cellar, and carrying empty ones away. People came in, drank, and went out, and there was seldom a vacant chair. Every one asked for beer, and when the supply ran out they ordered lemonade, until every bottle was sold. Wine was the last thing they desired.

I sat down close to the door. Teresina at the other end of the room caught my eye, and raised her eyebrows as much as to say 'lemon squash?' I nodded in answer.

Close by three men were playing murra, quite unconcerned at the noise they made. They were Cristofolo's two sons-in-law, and a third man who was a stranger. I guessed him to be the rich grocer from Florence, Dominica's husband. He could not speak the dialect but played murra in Italian, and probably, out of consideration for their guest, the other two did so as well. Instead of the familiar 'ü, du, tre, quater, sich, sei, set, ot, neuf,' big Giuseppe, in a chastened way, was calling ' uno, due, tre, quattro, cinque,' etc. It worried him so much that he lost.

As I was finishing my lemon squash, Nino came and spoke to me.

'Signora, forgive me,' he said, 'I have so little time to talk to you to-day—you see how busy I am. We never expected such a crush, so many people have never been to the festival before. If only I had another hundred bottles of beer... You were at mass?'

'Yes,' I answered, 'and I am wondering why the priest hadn't troubled to shave.'

'You are not the only one to say that,' said Nino, and then, leaning across the table, he whispered, 'perhaps he was too drunk to hold a razor!'

'Nino—don't' ... I protested. 'When every one else is so tidy I was surprised to see his face with a six days' stubble. No doubt he means to grow a beard.'

'Oh, yes—likely,' he answered sarcastically, going off to serve a customer. Presently he was back again.

'Did you hear what my father-in-law said to him? ... He met him in the street and said: "I suppose you are going to shave for the afternoon service?" They all listened for a reply, but the priest never answered him at all.'

‘Can you tell me who those two girls are,' I asked, 'one in a pink skirt—the other fat, with a cast in her eye?'

‘Ah—Negretti's two girls ' I could see by his face that he did not care for them. I waited for further information. 'They are back for a holiday,' he went on, 'they work as milliners in B—. They pretend to be ladies.'

'So I see '

'They come and put on airs—and hardly any one is good enough for them to look at. They are not a bit like you.'

'No,' I answered, 'they are much more elegant.'

'Signora,' said Nino, resting his arms on the table, 'you may wear an old dress, but you have money in your pocket. It is that which counts. Their elegance is scarcely skin deep, and their pockets don't contain a palanca,... Those girls have to starve themselves in order to satisfy their vanity.'

'One of them looks quite fat,' I remarked.

'Perhaps—but they lead a dog's life in order to dress like ladies. They think then they are better than we are.... There is nobody I should like to kick more! You, signora, you talk to us all, it makes no difference to you whether we are poor or not, you treat every one the same. But those girls, who were born here, walk through the village not deigning even to notice some of their neighbours!'

The church bells rang and I hurried back to Cominelli's house. The dancers were crowding down the passage into the street. Rosina was putting the finishing touches to the two little girls. They were to take part in the procession. Both wore white dresses with wreaths on their heads and flowing ribbons.

The church was even more crowded than in the morning, many more people having come to the village during the afternoon. Several pews were set apart for the girls taking special part in the procession. They were in white, and two whole benches were filled with children dressed up to look 'like angels.'

The service, which was conducted at the special altar in the body of the church, was very short. It was followed by a sermon. Our priest sat listening to the preacher with the most benign expression on his face, nodding his head from time to time. It was a pity he hadn't shaved.

At the close of the service Ghita sang a solo. Too shy to stand up by the organist where she could be seen, she crouched down behind the barricade. She had a nice voice and sang with such simple devotion that it touched everybody.

The large doors at the back of the church were then thrown open and the sunshine streamed in. The female part of the congregation stood up and walked out, and formed into two lines of single file with a space in between. At intervals in this space walked girls and youths carrying banners and other emblems.

Ghita headed the procession, dressed in white with a white veil and carrying a big bouquet of flowers. Pina walked on one side of her and my little girl on the other, both clutching her skirts.

The procession walked slowly across the piazza and into the shady street, chanting the same dismal Litany that I had heard when the fields were blessed. Girolomo was busy putting everyone in their places, and he came running past us in order to ask Ghita not to walk so fast. He was very hot.

When all the women had come into line, the band formed up three abreast, trumpeting a martial tune which more than half drowned the Litany, and was in quite a different key, not even a minor one. No one, however, paid any attention to that.

After the band came httle children hand in hand, carrying nose-gays, and behind them, under a large canopy, walked the three priests in gorgeous vestments, and the little boys carrying censers.

Then came the image of the Madonna. It was carried on a stretcher supported by four youths. Nino was right, the Madonna was heavy. She was topply too, and had to be supported on either side by a man, tall enough to reach the brass rod of her canopy.

The rear of the procession was brought up by two single files of hatless men.

We walked, chanting, down the street, past Giacomina's house and the red and yellow bedspread, past Toni's and Cominelli's, right into the sunlight, where the new road branched off along the edge of the cliff back to the church. The new road was very wide and under a large green archway stood a common table. We passed it by, but when the priests reached that point they stopped, and the image, swaying as the youths staggered along, was carefully placed on the table. The band stopped playing.

The priests recited prayers, and we knelt where we stood, and prayed and beseeched the Madonna to keep off the hail.

Then we rose to our feet and walked slowly on, chanting again. The band struck up another martial tune. Pina, forgetting the occasion and hearing only the band, tripped along with light steps, still clutching Ghita's skirts. On nearing the church, we could hear the organ pealing forth yet another tune. It was a strange medley of sounds.

We crowded in, and the Madonna was put back on the altar.

Ghita's two youngest sisters stood before the image and recited. Afterwards every one filed past the priest, and kissing the Relic he held in his hand, followed one another out of the church.

The band was playing in the piazza. It was a little cooler. The sun was hidden behind the crags, and would not be seen again to-day. The sky was pale and clear. We strolled about, speaking to friends and listening to the music. Several women were hanging out of upstairs windows talking to friends below. From the inn came the sounds of murra.

Every one was and looked happy. It had been a successful day, una bella festa. The villagers were flattered by the number of strangers who had come, the strangers were more than satisfied with the hospitality and goodwill of the people of Campiei. The bandsmen considered that they had been so well treated that they even offered, to come and play at an autumn festival for no remuneration!

The two policemen, who had paid a formal visit to the village during the afternoon, went back to the town whilst it was broad daylight. It was not thought necessary that they should remain in the village during the evening.

Toni sought me out in the piazza, he wanted to hear me speak English with a relation of his, who had been to America. It thrilled Toni to listen, understanding not a word. Perhaps he would have been surprised if he had understood what we were so seriously discussing. After a few preliminary sentences we spoke as follows:—

'Any bugs in England?' asked the relation.

'Bugs? ...oh, yes, of course, there are bugs in England,' I answered.

'Also in America,' he informed me, 'plenty bugs everywhere, but in Italia, no.'

'There are no bugs here at all?' I asked.

'No, nowhere in dese parts—but plenty fleas,' he went on.

'Yes,' I answered, 'and papatas,' referring to the little midges which infested my room at night.

Our conversation, perhaps fortunately, was broken off by Giacomina. She wanted me to come to Cristofolo's house and make the acquaintance of his daughter Dominica from Florence. We started off, but remained to loiter, because the band was playing its last tune. The bandsmen came from a village eight miles away, they had walked over in the morning, and were walking all the way back now. They were given a very cordial farewell.

Some of the visitors from more distant villages had already left—others were leaving. A good many were spending the night in the village, and some of the people from the town stayed until quite late, and went home together in a party. The street was still crowded and every one was strolling there or looking out of the windows overlooking it. A few careful housewives were taking in their bedspreads.

Giacomina took my arm and we walked up the street with a word for nearly every one we met. Rosina called out that she was just going to get supper at Cominelli's, would I come in half an hour, and continued an animated discussion with Stefen.

I was stopped by a stranger, who told me that he knew me quite well, but was quite sure I'd never seen him. He laughed at my puzzled expression, and then explained that he was the expert who had helped Toni burn the lime—he had watched me put in the faggots. A friend called him and he passed on. We turned up the mountain road and the crowd thinned. Outside Cristofolo's green gate the road was empty.

A large party was assembled in Cristofolo's kitchen, most of them relations. They sat on chairs round the walls. In a corner Bigi was playing the mandoline to Tona's strummed accompaniment.

I was introduced to Dominica and her husband, and to a friend of hers from London, an Italian lady whose husband kept a laundry in Soho.

I liked Dominica. I had expected her to be a little pretentious and overdressed perhaps, like the two girls I had seen in church, but Dominica was not like them. It is true her clothes were costly and fashionable, but they were in good taste and she knew how to wear them. She was not beautiful, nor a bit like Bigi or her sisters, but very tall, pale, and reserved. The thing which most struck me about her, was the admiration her husband showered upon her. He was sitting by her now, holding her hand, and looking unutterably docile. It was evident that she lived in the sunshine of his unconcealed admiration, and to keep it from becoming embarrassing she was a little haughty with him—just to keep him in his place.

There was another stranger in the room, Teschini, a friend of Dominica's husband, who also kept a store in Florence.

I sat down by the lady from Soho, She was very beautiful, wore big pearl ear-rings and a scarlet overall over her dress. I spoke English to her and Dominica, and we made pleasant remarks, and drank vermouth.

'Ah,' sighed the lady from Soho, thankful to be amongst her own countrymen again, 'Italians are jolly—arn't dey? Never dull.'

'No,' I answered, thinking of the hail, 'nothing seems to damp their spirits,'

Then turning to Dominica she said loudly, 'De signora is a person of education—a lady—I can 'ear dat by de way she talk English,'

Bigi struck up a tune, the table was put on one side and we had a few dances. Then thinking of Rosina's soup, and that Annetta might be waiting for me to go before she began her preparations for supper, I took my leave and found Rosina looking up the road for me. She had already ladled the soup into plates which stood steaming on the table. Bortolo had gone home to milk the cow, the boys were somewhere in the village, she said—she didn't know where.

'I suppose,' said Rosina, blowing her soup, 'that you have heard that there will be dancing to-night—in the house opposite.'

'But isn't it empty?' I asked, half expecting to hear that it was inhabited. Several desolate looking houses in the village, which I had taken to be empty turned out, on investigation, to be occupied. I could never tell from the outside.

'Yes—it is empty,' she said, trying to sip the hot soup from her spoon, which she held with an elbow on the table. 'It belongs to Gheco, but he prefers to live in the house down by his lands,'

'The accordion won't play, I hope,' I remarked,

'No, signora, it will be our own players... Here,' she went on, stretching out the bottle—'have some wine,' ... I held out my glass which she filled, 'Why don't the boys come to supper? It is strange that they never can do as they are told...'

'You would find life very dull,' I answered, 'if Riccardo was a good and obedient boy.'

Rosina laughed.

'Ecco,' she went on presently, 'I hear the mandoline... Signora—you will burn yourself if you eat so quickly!'

It was not long before I ran up the outside stairway, and stood in the kitchen of Gheco's house. The players were sitting in a corner, but not many dancers had come yet. La Macuccia sat on a chair fanning herself, and I sat down beside her. She was full of a letter received from her youngest son, who had been three months in America. 'He is doing well,' she told me proudly, 'he has sent money this time, four hundred francs—there is money in America—have you seen my other son, the policeman?—he is home for a few days on leave.'

I had not met her son.

'No doubt you have seen him,' she said, continually fanning herself and me by turns, 'he wears a white suit.'

I knew whom she meant, and it was not long before I danced with him. Introductions are not necessary at Campia, you dance with whomever asks you to, but of course you can always refuse.

Apollonia scandalised some people by dancing. They said it was much too soon after her father's death, but she had her own opinion on the subject. She wanted to learn, and Gheco had been teaching her the steps...

Sometimes when we were too hot and out of breath, some one would stand up and sing, and those not too exhausted would join in the chorus. Of course 'Tripoli' was sung—twice over. At other times we sat out on the balustrade or the stairs, where it was a little cooler than indoors. It was a calm evening, the sky was cloudless and the stars shone bright. The moon was just rising.

Some of the younger men had been pulling down the triumphal arches and carrying them away to the new road. Here they had made a glorious bonfire, and all the village children had thoroughly enjoyed themselves.

Most people were indoors now. The two inns were crowded, and I could hear the sounds of murra from more than one house, otherwise the streets were very quiet. The young men came back from the bonfire and sat down by the fountain to sing. They sang in parts and it was a pleasure to listen. As each song was finished, clapping was heard, and from dark doorways unseen listeners cried 'bravi.' Now and then some one came clattering down the mountain road and passed down the street into the shadows. The moon rose higher and began to shine on one side of the street.

Punctually at ten o'clock the inns closed, and the men came out and dispersed. This was Rosina's golden hour. Some of the thirstier souls found their way into Cominelli's kitchen, and Rosina fetched out her wine bottles. Gioan was amongst the number, and was as voluble as wine could make such a reticent man. Bertoldi was drunk and broke a glass. Wine did not make him the less good-natured, he was perfectly aware of the condition he was in, and deplored it. He was so drunk he couldn't walk home, and slept all night on some-body's doorstep. Rosina—who had been selling him wine—said it was disgraceful.

It was very late when we stopped dancing. As usual it was the players who first left the room. They walked down the steps and played a farewell tune down in the road.

The village was hushed, the murra players had gone to bed, and the full moon, high in the heavens, shed its clear hght into the narrow street. The white houses stood luminous among mysterious dark shadows.

The players walked up the street, but at the fountain they stopped, and standing in the magic light in the middle of the crossing, they began to play again... one tune after the other.

We stood stening by the wall. No one spoke a word. It was indescribably beautiful, the string instruments, the moon and the phantom musicians whose black clothes were indistinguishable against the shadows behind.

They stood playing for a long time.

At last Giacomi stopped and said, 'It is enough.’

'Bravi, bravi,' we called; 'bravi, bravi,' came from the dark shadows round about, which suddenly became alive with people.

'Good-night,' we called out to each other, although it was too dark to distinguish any one. 'Good-night,' they called back, 'goodnight,' and we went home.

Gordon, Lina Duff. Home Life in Italy: Letters from the Apennines. Methuen & Co., 1908.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.